Dutch companies have sourced their business services activities to nearshore locations for decades. The main reasons to locate these business services in, for example, Eastern Europe, are because of the availability of qualified personnel, a better cultural fit compared to offshore locations (e.g. Asia) and labor arbitrage. However, due to the changing macro-economic environment, the question arises whether this type of sourcing will change in the years to come. To produce an outlook for the European market, we have conducted extended research into the European market to predict the main macro-economic variables on the sourcing decision. The consultation will indicate whether the main sourcing hubs are still a good option for BPO/outsourcing solutions or whether the Western European companies will consider ‘backshoring’ their activities to their home countries.

Introduction

Companies are constantly striving to improve their core competences and reduce costs by finding the optimal sourcing strategy. Although in the past only ‘non-core’ activities (those activities that are not involved in the value proposition of the business) were bundled together for outsourcing, these days businesses and scholars have also shed light on the possibilities of sourcing ‘core’ activities (those activities related to a company’s strategy) ([Mohi13]). Hence, sourcing strategies have been defined for these bundled activities: domestic in-house, domestic outsource (third party in same country), captive offshore (different location of same company) and offshore outsource (third party abroad) ([Tall11]). For the last of these, locations in different continents or neighboring countries (nearshore location) can be considered to optimize the value-creating factors ([Merk14]) and add value by either specializing or innovating ([CBI15]).

However, the global business landscape has changed over the last two decades. Some politicians and research organizations are convinced that the unfavorable macro-economic environment abroad and new technological advantages drive companies to backshore processes, improving the company’s global competitiveness ([Foer16]). Especially manufacturing, IT and services companies in industrialized countries are reconsidering their sourcing strategy and looking further than mainly labor costs and arbitrage ([Merk14]).

Most of the existing literature about this type of sourcing only examines the motivations for manufacturing companies. Manufacturing companies have chosen to relocate their activities back to their HQ (backshoring) ([Frat14]). It is found that moving back the processes in-house leads to ‘renewed job creation’ ([ILO13]), higher domestic demand for goods (e.g. machinery) and a decline in gas costs ([Geor14], [Merk14]).

A new development in this strategic process is the emerging role of global business services. Although it has been found that these companies often have globally dispersed activities allowing them to gain access to ‘local resources, knowledge and capabilities’, and thus become innovative and remain competitive ([Bagl10]), currently only around 20 percent of the backshoring activities concern IT and business services ([Merk14]). However, the existing literature neglects the drivers for Global Business Services companies to relocate their activities back to their headquarters. Currently, there is a gap in research for this sector. Therefore, our article will investigate the reasons and the impact of backshoring.

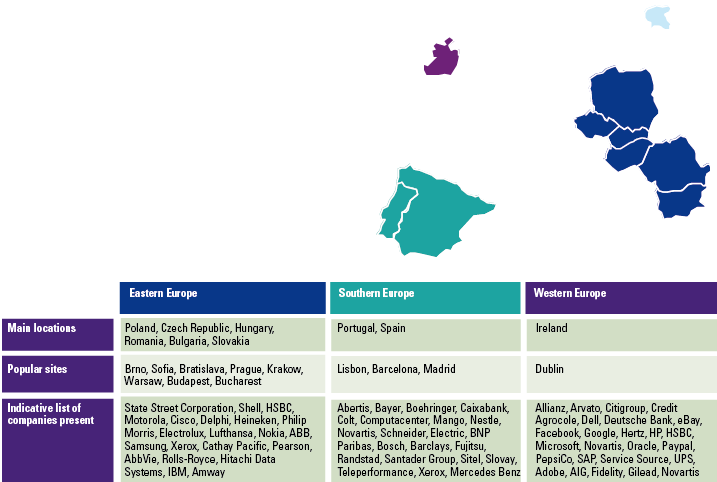

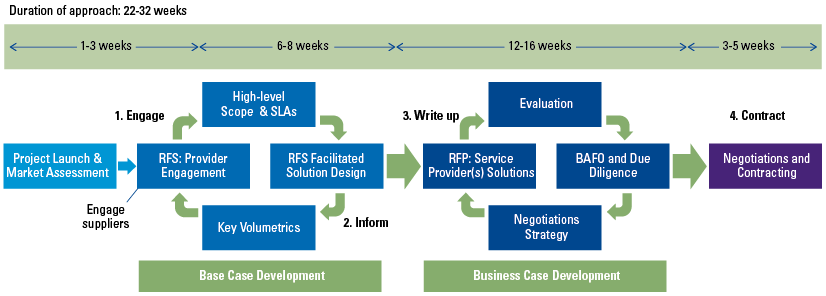

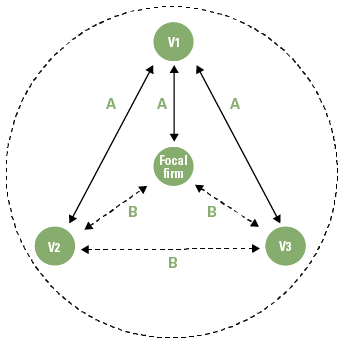

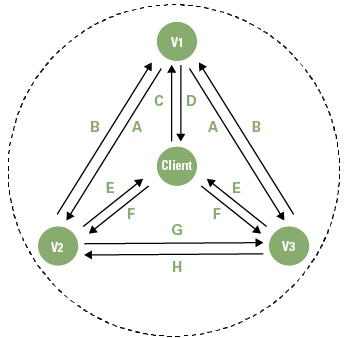

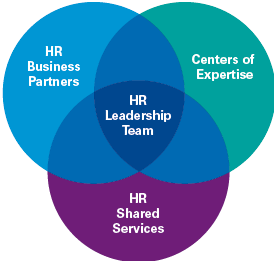

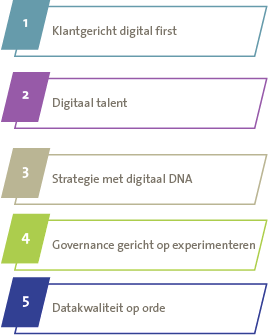

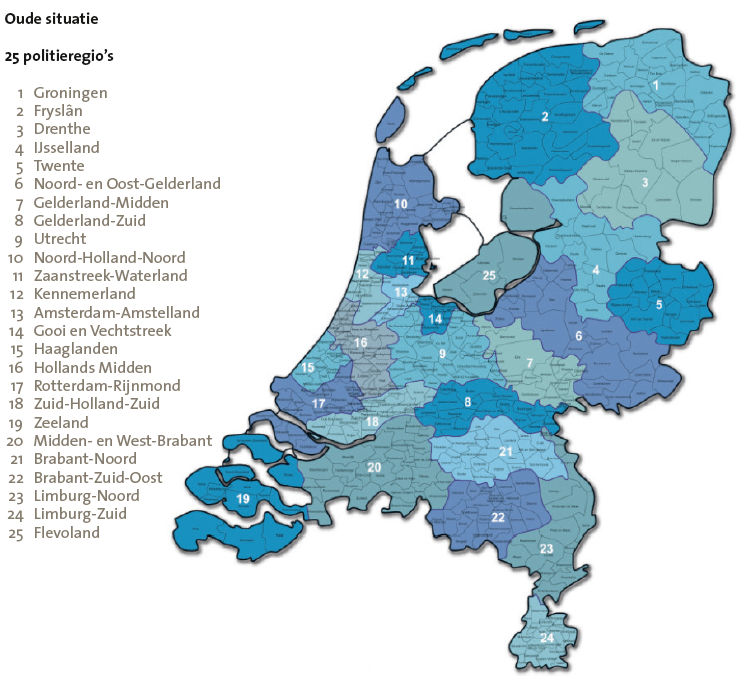

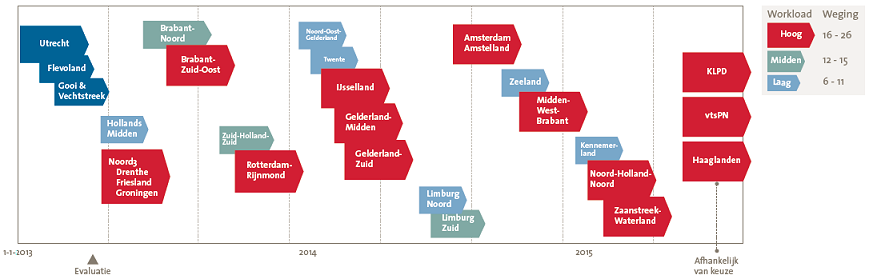

We are inspired by current macro-economic developments (e.g. Brexit, Ukraine war and the right-wing political preferences), which may imply a favorable environment to backshore business service processes from nearshore locations back to the home country. As such, the scope for this paper is solely focused on how European trends can influence the decision process for Dutch companies to reconsider their business services souring strategy. A macro-economic analysis will be conducted using the ‘PEST’ model of [Thom07]. This analysis is used to point out the different macro-economic factors (political, economic, social, technology) which influence particular choices about the sourcing strategy of the business services functions. The scope for this research is based on the ‘most-known’ outsourcing hubs in Europe, with a sufficient presence of SSCs and service providers. These hubs are: Eastern European countries, Southern Europe and Western Europe (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of sourcing hubs. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The degree of political movements

As described in the previous section, several groundbreaking events have impacted the integration of Europe (e.g. Brexit and the Ukraine war). However, these are not one-off events, but are part of the change in the political stability in Europe during the last few years. Whereas the continent is known for integration and collaboration within a strong community as the EU, several events have taken place which do not favor this integration. In Eastern Europe, Poland is trying to be suspended temporarily from European decision making and it is uncertain how Brexit will affect Western Europe politics. Another trend is that parliaments are shifting to right-oriented parties. This can imply self-sufficiency within these countries as the perspective and preference of these right-oriented parties are far more conservative. However, the political stability for the countries is still perceived to be high and at this point does not create major triggers to ‘re-source’ their (global) business services activities.

Central and Eastern Europe

As Eastern Europe is one of the most favorable locations to ‘nearshore’ business services for Dutch companies, we start with an analysis of this part of Europe. Recent elections show a more conservative/right-wing/populism trend compared to elections held before 2015. Countries such as Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland are being dominated by (ultra)nationalist parties. These parties are often led by former businessmen, who only recently entered into the political arena. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the political stability and governmental effectiveness of these ‘nearshore’ countries are perceived to be ‘stable’ to ‘moderately stable’. The only country facing some political instability is Poland. The country’s power has been centralized under the control of the president. The president has the right to veto legislation or send it for review to the Constitutional Tribunal. This mechanism is in contradiction to the principles of a democracy, and it has been pointed out that this has the highest attention of the European Commission. The EU has initiated a vote for each EU Member State, based on article 7 of the EU treaty, to temporarily suspend Poland from European decision making. Romania and Slovakia have a more left-center parliament. Elections were held in 2016. The EIU describes a stable political environment for both countries, however the effectiveness of the Romanian government is perceived as the least favorable of all countries analyzed.

Southern Europe

Well-known Southern European ‘nearshore’ hubs are Portugal and Spain. Although both countries have had a stable political environment during recent years, there has been a major event within Spain which made the environment less stable than before. Historically, Spain is known for having several movements in the country that fight for the independence of specific regions. In recent years, these political movements have been toned down within the public arena. One example is the ETA that has officially stated that it will disarm their party and only continue to promote their message through dialogue. Furthermore, the region of Catalonia recently initiated a referendum to decide on their regions independence from Spain. The central Spanish government forbid the referendum and intervened in Catalonia. The referendum was therefore held illegally (from the perspective of Spain). President Mr. Raju has suspended all independent power of the region and centralized it in Madrid.

Western Europe

In June 2016, the British people voted for ‘Brexit’. In Western Europe, only Ireland is recognized as a ‘nearshore’ hub. The authors did not choose to elaborate extensively on Brexit itself. However, since Ireland is a direct neighbor of Great Britain, it will affect the politics of this country. In December 2017, Prime Minister May and President Juncker entered into a provisional agreement which indicated no ‘hard border’ between the Republic of Ireland and Northern-Ireland, which seems to be favorable for the Republic of Ireland. However, a formal agreement between the EU and Great Britain about Brexit has to be negotiated more extensively and this may affect the stability within this part of Europe. The (left-wing) Irish political system is known as stable and shows good governmental effectiveness.

Economic factors affecting business

Companies are constantly exposed to contingent disturbances (also called ‘environmental uncertainty’), such as volatility and unpredictability ([Mili87]). Consequently, they outweigh the benefits of locating the outsourced activities in nearshore locations. This is primarily driven by the unfavorable changes in the economic environment in low-cost countries (classical ‘offshore’ locations, such as Thailand or China) in the last years due to, among others, appreciation of the currency and increased costs of labor, production and natural resources ([Ellr13]). This change made nearshore (European) locations more attractive, such as Eastern Europe. Although the availability of (relatively low-skilled) labor and wages are less favorable in Eastern Europe compared to (South-East or Western) Asia, the cultural, educational, geographical and language proximity is better aligned to advanced European countries ([Amar16], [UN17]). On top of this, many countries belong to the European Union, and thus guarantee extent degree of regulatory certainty, employee mobility (access to language skills) and the ease of a unified currency ([Amar16]).

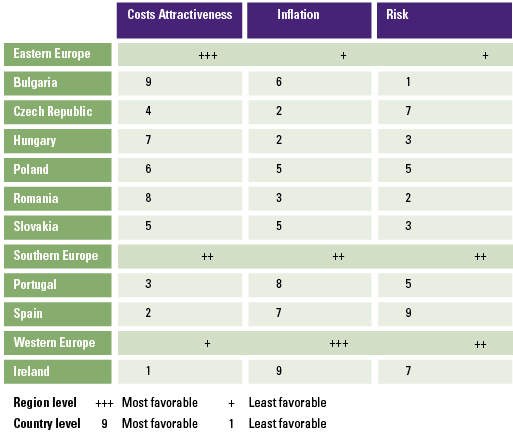

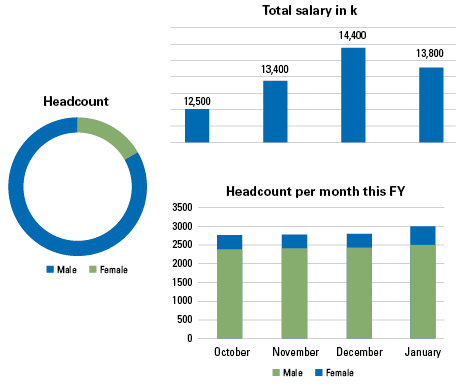

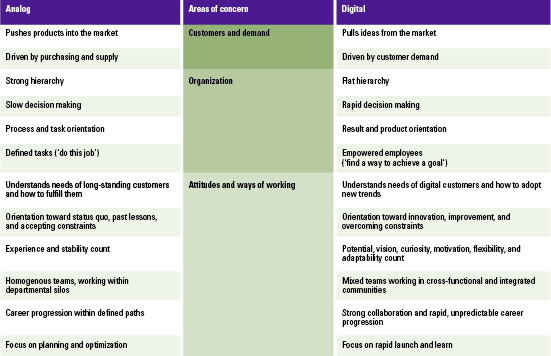

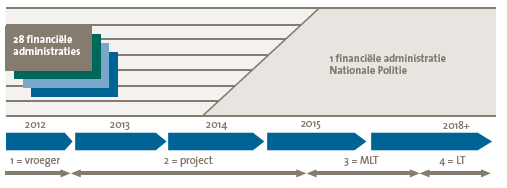

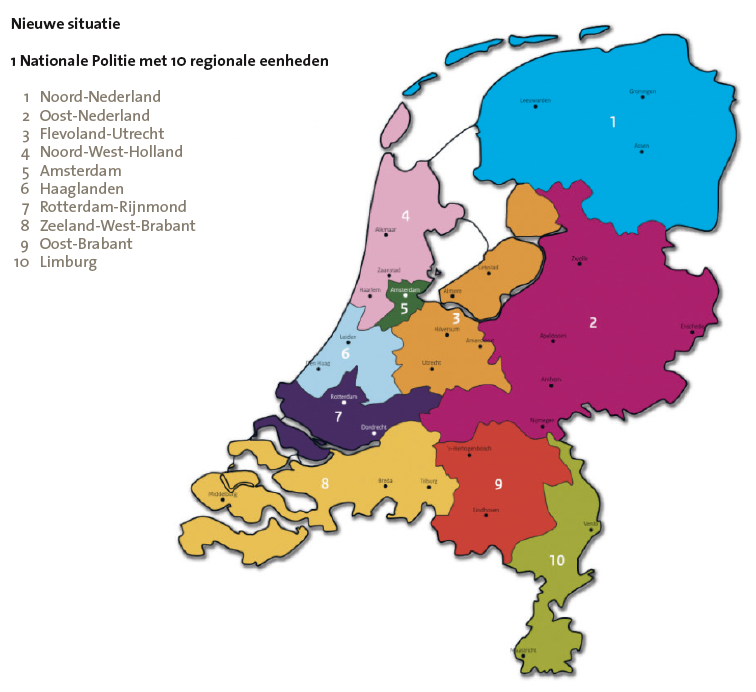

In order to compare the three main outsourcing hubs in Europe, we created Table 1. The economic environment is determined by cost attractiveness (employment costs of business services, office rents per m², corporate tax rates), inflation rates (inflation last year and CPI last year), and risks (country and business environment).

Table 1. Overview of economic indicators per outsourcing hub and countries. [Click on the image for a larger image]

In short, the table shows that Eastern Europe is very attractive due to its relatively low costs for employment, corporate taxes and offices compared to the major outsourcing countries in the South and West of Europe. Thereby, the inflation differences among the three regions is negligible, and varies per country. The economy in Eastern and Central Europe is characterized by its strong GDP growth (approx. 5% annually), driven by the domestic and export demand. This strong performance is also linked to the loose fiscal policies, tight labor market and high number of investments ([Bouz17]). The business outsourcing market is gradually improving as this region continues to develop.

Central and Eastern Europe

Although Bulgaria is the most cost attractive compared to the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia, the risks of doing business in Bulgaria are higher compared to all other countries. Nevertheless, Bulgaria is seen as a developing destination in Europe for outsourcing activities, but has currently the lowest penetration rate compared to other locations in Europe. In contrast, the popularity for the strongest economy in this region, Poland, has risen significantly and is ranked as the largest outsourcing location in Europe (and number 9 in the world) due to its stable economy ([Amar16]). Currently, over 400 BPO Suppliers are located in Poland, mainly spread across the cities Krakow and Warsaw ([Amar16]). Both cities are leading and highly mature for business services in Europe due to their talent pools and multilingual work forces. Warsaw, which specializes in Finance, Accounting and Customer services, is becoming the biggest competitor of Budapest (Hungary) in this field. Romania is ranked second in Europe and thus beats the Czech Republic despite the high-skilled labor force in the Czech Republic, mainly because of Romania’s expansionary fiscal policy, high cost attractiveness, high consumer spending and a significant labor force in business services ([Bouz17]).

Southern Europe

South European countries show relatively less economical risk (country and business risk) compared to Eastern Europe. Despite the EU/IMF bailout of € 78 million in 2011, Portugal is now one of the fastest growing economies in Europe. It has restored its wages and pensions to the level before the Global Financial Crisis ([Rank17]). This economic improvement mostly attracted activities to serve the American, financial and IT markets, with companies such as Randstad and BNP Paribas. Moreover, Spain is currently the fourth largest economy and has rapidly recovered from the crisis. The country is known for its high unemployment rate (17% in July 2017), new reforms to fire employees more easily, rising inequality and low wage growth ([Rank17]). The capital city Madrid and Barcelona are especially popular, because of the young work force, good infrastructure and the high number of business graduates.

Western Europe

Ireland, representing the West Europe outsourcing hub, has the highest costs for doing business. But the risks to outsource are not entirely negligible. Economic developments in Europe can have a huge impact, especially for an open country such as Ireland, since the economic growth and employment is greatly affected by international trade.

The movements in sociology

As stated by research of [Khan11], skilled human resources are one of the key success factors for outsourcing. Trends and movements in sociology can help to explain this key success factor. The EU has initiated a platform which analyzes European sociological trends. This platform is called the European Strategy and Policy Analysis System (hereafter: ESPAS). The platform points out five major trends:

- the rise of the global middle class;

- a growing ageing population;

- employment and the changing labor market;

- evolving patterns and impacts of migration;

- connected societies, empowered individuals.

These trends are summarized into four main topics:

- rising inequality and more vulnerable groups;

- the consequence of a new global consumer class;

- adapting to a new demographic reality;

- opportunities for individual empowerment but risk of a divide.

As described in the introduction of this section, one of the key success factors in outsourcing is skilled human resources. A lack of high-skilled resources could therefore be a trigger for the ‘backshoring’ phenomena. We chose to solely concentrate on these sociology aspects which suits best to the availability of skilled labor.

The phenomena of rising inequality and more vulnerable groups have been described as the rising gap between rich and poor within the EU. This gap has widened due to the financial crisis of 2008 and it is expected that this gap will increase further in the next decades. This implies unemployment for vulnerable groups. Along with the increasing gap between rich and poor, it is expected that this will not be in line with the changes in the labor market. It is forecasted that there will be an increase in jobs in the technology sector, whereas the supply side predicts that there will be a shortage in medium and high-skilled workers. Both factors can influence the sourcing phenomena. Whereas, in practice, outsourcing decisions are mainly taken based on a favorable business case, the increase between the rich and poor countries within the EU can imply a higher percentage of labor arbitrage and does not imply any trigger for the ‘backshoring’ phenomena. On the other side, a war on talent is being declared due to the lack of medium and high-skilled labor. This can be a trigger for the ‘backshoring’ decision, since the Dutch workforce is known for its medium to high-skilled workforce.

The new demographic reality is being described as a distinction between low-income countries and high-income countries. The low-income countries ‘do have a window of opportunity due to high fertility and a decline in infant mortality’. This increases the countries long-term working population and can ‘generate work opportunities for younger generations’. The high-income countries are being hit by an ageing population, which implies a decreasing working population. The last sociological topic is described as the opportunities for individual empowerment but risks of a divide. The empowerment of individuals, and therefore their access to education, is being increased due to economic development and technological innovation. Empowerment of the labor workforce of low-income countries and empowerment of women are being stimulated by these two aspects. The new demographic reality and the empowerment of individuals should therefore be rather a trigger for outsourcing than for ‘backshoring’.

Technological developments

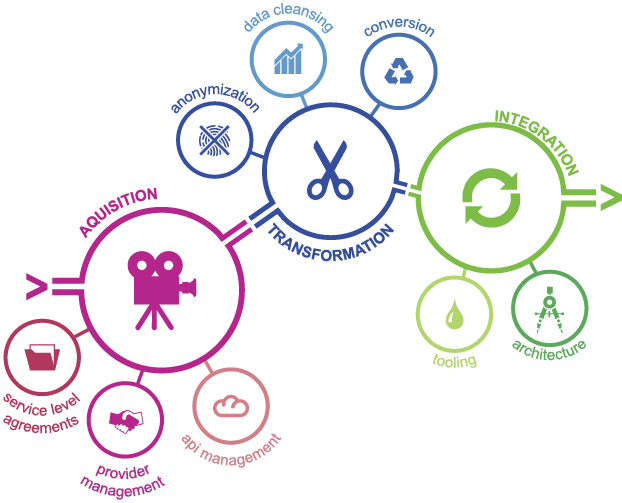

We are living in an era of continuous technological improvements. These technological developments, and especially digital technologies such as cloud computing, data analytics, artificial intelligence and robotic process automation (RPA) are generally transforming the business environment and generate interest for, among others, security, control, storage and systems. Consequently, new technologies impact the production and service landscape of businesses.

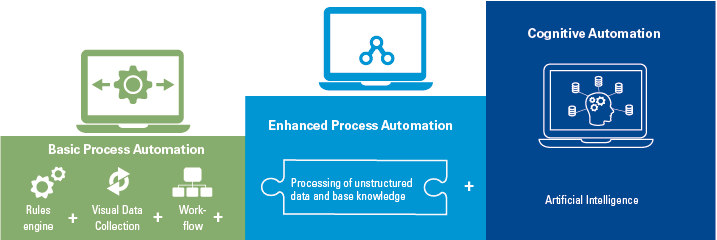

Firstly, the opportunities for cloud computing (e.g. IaaS, PaaS, SaaS) enable flexibility in economies of scale and costs. This facilitates working in offshore/nearshore locations, as you have access to the cloud anytime and anywhere. However, companies have to guarantee data security, which is often inferior to the onshore location ([CBI15]). Secondly, gathering and analyzing big data has become a standard for European companies as this gives insight into potential innovation, sales, marketing, and business intelligence ([CBI15]). Although companies prefer data analytics in-house, the high level of investments and resources make it attractive to outsource. Moreover, it allows the company to focus on its core competences. Next, robotic process automation (RPA) is a process automation method to share or support a human interacting with a computer. This technology allows the ‘take over’ of repetitive, rule-based tasks (also called Basic Process Automation). In this way, companies are not spending money for an employee performing tasks on a computer and they want to guarantee a high level of quality, efficiency and speed, making it attractive to create a computer that does the same job. Although some would argue that these information and communication tools will replace employees and lead to cheaper, high-quality work – and thus have a negative effect on offshoring, e.g. [OECD15], others argue that the emergence of RPA is a move towards value-driven and complex activities with high-value added. In this case, reference is often made to Enhanced Process Automation (EPA) – e.g. the ability to generate learning capabilities, recognize patterns, work with unstructured data – or, even more complex, Cognitive Automation – e.g. self-learning, hypothesis generation, evidence-based learning. Artificial intelligence is also an example of cognitive automation. Although this technology is looming on the horizon, it can affect the outsourcing business by applying the right set of skills and investments. Intellectual offshoring may stay in-house because of minimal economic incentives, and thus more industry experts can be hired to even improve the core business.

Are the current BPO Suppliers able to anticipate the new wave of technological improvements? Does the emergence of such technologies support BPO Suppliers in identifying and offering new service capabilities that boost the existing offshore relationships?

Conclusion

Backshoring in Europe is not a major sourcing trend at this moment. Although technological improvements make it possible for a company to backshore its business services to the home country and thereby retain control over its own activities, the technologies are also accessible for BPO Suppliers. Hence, the costs of retransition would not outweigh the benefits. In addition, there are some uncertainties which may also affect the decision making of the business managers. These uncertainties are based on the identified risky macro-economic factors abroad (a further instable political environment and social and economic uncertainty) and attractive home country advantages (e.g. decrease of labor costs, increased productivity through technologies and the emerging extent of automation). Backshoring also implies benefits because the company is not dependent on an external BPO Supplier, and thus has full control over the quality and processes. However, there are still decisive drivers to offshore business services. Cost reduction is still the most important factor for first generation outsourcers, providing opportunities in Eastern Europe. Other factors are access to a global talent pool, focus on core competences and efficiency ([CBI15]).

References

[Amar16] R. Amaral, The most attractive European countries for outsourcing, Raconteur, September 2016.

[Bagl10] E. Baglieri, M. Bruno, E. Vasconcellos and A. Grando, International technology cooperation: The Fiat auto case, Revista de Administração e Inovação, 2010.

[Bouz17] A. Bouzanis, Economic Snapshot for Central & Eastern Europe, Focus Economics, 2017.

[CBI15] CBI, CBI Trade Statistics: Outsourcing in Europe, 2015.

[Ellr13] L.M. Ellram, W.L. Tate and K.J. Petersen, Offshoring and Reshoring: An Update on the Manufacturing Location Decision, Journal of Supply Chain Management, 2013.

[Foer16] K. Foerstl, J.F. Kirchoff and L. Bals, Reshoring and Fing: Drivers and Future Research Directions, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 2016.

[Frat14] L. Fratocchi, C. Di Mauro, P. Barbieri, G. Nassimbeni and A. Zanoni, When manufacturing moves back: concepts and questions, Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 2014.

[Geor14] K. George, S. Ramaswamy and L. Rassey, Next-shoring: A CEO’s guide, McKinsey Quarterly, 2014/1.

[Hand13] S.M. Handley and W.C. Benton, The influence of task- and location-specific complexity on the control and coordination costs in global outsourcing relationships, Journal of Operations Management, 2013.

[ILO13] ILO, Re-Shoring in Europe: Trends and Policy Issues, Research Department Briefing, 2013.

[Khan11] S.U. Khan, M. Niazi and R Ahad, Barriers in the selection of offshore software development outsourcing vendors: an exploratory study using a systematic literature review, Information and Software, 2011.

[Merk14] C. Merk, J.Silver and F.D. Torrisi, Rebalancing your sourcing strategy, McKinsey, 2014.

[Mili87] F. Miliken, Three Types of Perceived Uncertainty about the Environment: State, Effect, and Response Uncertainty, The Academy of Management Review, 1987.

[Mohi13] M. Mohiuddin and Z. Su, Offshore Outsourcing of Core and Non-Core Activities and Integrated Firm-Level Performance: An Empirical Analysis of Québec Manufacturing SMEs, M@n@gement, 2013.

[OECD15] OECD, Robots in Manufacturing: A First Look at the Evidence, OECD Publishing, 2015.

[Rank17] J. Rankin, Weakest Eurozone economies on long road to recovery, The Guardian, 2017.

[Tall11] S. Tallman, Offshoring, Outsourcing, and Strategy in the Global Firm, AIB Insights, 2011.

[Tate14] W.L. Tate, Offshoring and reshoring: U.S. insights and research challenges, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 2014.

[Thom07] H. Thomas, An analysis of the environment and competitive dynamics of management education, Journal of Management Development, 2007.

[UN17] United Nations, World Economic Situation and Prospects, 2017.