Today, IT multisourcing is considered to be the dominant sourcing strategy in the market. However, the way in which clients and vendors exchange information and create value within such arrangements can be quite a challenge, due to interdependencies. This paper explores an IT multisourcing arrangement in more detail, to identify challenges and provide a strategy to overcome these challenges and create value. Based on what we have learned from various IT multisourcing arrangements, we have developed a reference model that can be used by clients and vendors to govern their eco-system, and as such, encourage value creation.

Introduction

As the market for IT outsourcing services increased significantly over time, IT vendors had to specialize ([Gonz06]) to distinguish themselves and remain competitive. IT outsourcing arrangements evolved from a dyadic client-vendor relationship to an environment that includes multiple vendors ([Bapn10], [Palv10]). Currently, a multisourcing strategy is said to be the dominant modus operandi of firms. The shift from single sourcing towards multisourcing arrangements provide firms with benefits, such as quality improvements by selecting a vendor perceived as best in class, access to external capabilities and skills, and mitigating the risks of vendor lock-in. Firms that are involved in collaborative networks have to significantly invest in time, commitment and building trust to achieve common value creation and capturing by means of interaction between multiple sourcing parties. Within the context of IT multisourcing arrangements, which can be considered as collaborative networks or eco-systems, parties within such an arrangement need to coordinate their tasks due to interdependencies. However, it is important to consider how parties exchange information and knowledge and contribute to common value creation. Consequently, if parties are not able or willing to exchange information and knowledge this may result in barriers that affect common value ([Plug15]). Given this challenge, we argue that a holistic approach is required to delineate and analyze the relationships in an IT multisourcing arrangement as a whole. First, by using the metaphor of an eco-system, we are able to study interdependencies between clients and vendors, addressing themes like specialization and value creation. Second, parties that do exchange information and knowledge in an eco-system are influenced by the degree of openness, clear entry and exit rules, and governance, which correspond to Business Model thinking. The value of this advanced understanding is that common value creation within the context of IT multisourcing can be explained, while barriers that hinder these processes are identified.

IT Multisourcing and eco-systems

IT Multisourcing

Practice shows that an IT multisourcing arrangement is based on the idea that two or more external vendors are involved in providing IT services towards a client. The basic assumption is that external vendors work cooperatively to achieve the client’s business objectives. This may relate to IT projects, but also to more regular types of services, such as managed workplaces, IT (cloud) infrastructure services (e.g. IaaS and PaaS) and application management services ([Beul05]). Importantly, collaboration between parties in a competing IT multisourcing arrangement is key to align their interests, avoid tensions, and strive to achieve common value. Value is created through interaction and mutually beneficial relationships by sharing resources and exchanging IT services. In general, it is assumed that value is created by the client organization and its external vendors ([Rome11]). So, in value creation the focus is on a service that is distinctive in the eyes of the client. Value creation can be seen as an all-encompassing process, without any distinctions between the roles and actions of a client and the vendors in that process. Thus, an IT multisourcing environment can be conceptualized as an eco-system ([Moor93]), in which the client and vendors exchange information and knowledge to jointly create and capture value.

Eco-system

The idea of an eco-system is to capture value to the network as a whole, as well as take care that the client and vendors get their fair share of created value, or focus on capturing the largest part of the common value for themselves. The latter may negatively affect the sustainability of the eco-system. Eco-system thinking is more based on flexibility and value as core elements. Flexibility is necessary to respond to changing market developments, fierce competition, but also to opportunities. However, interdependencies between a client and its vendors may hinder the exchange of information and knowledge, and thus hinder value creation. This may lead to the underperformance of the eco-system in the long run. A strategy to overcome interdependence challenges, is that a client and its vendors regularly align their common interests, as well as their day-to-day operations. Hence, value creation and capturing needs to be established at a network/eco-system level while paying attention to the business models of all individual eco-system partners in order for an eco-system to survive. To achieve value in the eco-system as a whole, existing contracts between the client and vendors must include guidelines on how to collaborate and exchange information to support value creation.

Challenges

Specifically, from an operational perspective specifying long-term IT outsourcing contracts that span multiple vendors is complex and inherently incomplete, because clients and vendors have to deal with uncertainty and unanticipated obligations and incidents. Hence, clients should govern an eco-system beyond traditional contractual agreements and also build mutual relationships to support the exchange of information. However, this may cause a challenge as vendors may have conflicting goals and objectives, such as increasing their revenue at the cost of their competitor or the absence of financial agreements to fulfill additional tasks. In summary, key challenges that may arise in an IT multisourcing arrangement are: incomplete contracts, competition between vendors, willingness to share and transfer knowledge between vendors, and a lack of a client’s governance to manage the landscape as a whole. These challenges may hinder value creation, which is considered as the preferable outcome of establishing an IT multisourcing arrangement. To indicate value creation challenges, the case study below describes how a client and three key vendors deal with IT multisourcing challenges.

Case study

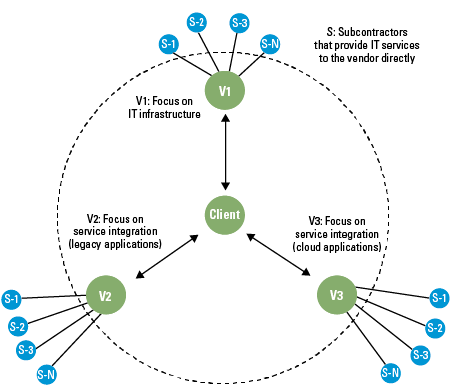

The client under study is positioned in the fast-moving consumer goods market and sells products in Europe. Importantly, the client’s business processes are highly dependent on IT to fulfill their customers’ needs in time, e.g. ordering systems, logistic function, replenishment, and payments. Today, the client is expanding its portfolio as online business is growing, while new store formats are being developed to extend the range of products. In order to retain their competitive position in the market, the client had to decrease the cost level of its IT. Currently, the client is in the midst of a business application transformation. This involves transitioning from various legacy applications to a new application landscape, developed to support new business strategies (e.g. online shopping). The setting for this case study focuses on the outsourcing relationships between the client and three key IT vendors. As illustrated in Figure 1, Vendor 1 is responsible for the IT infrastructure services, which are geographically dispersed across various data centers. Vendor 2, who acts as a service integrator, provides services related to various legacy applications. Next, Vendor 3 also acts as a service integrator, however, with regard to cloud services enabling applications that support the new business strategy. In addition, the client extended the multisourcing arrangement by contracting sixty smaller IT vendors, all acting as subcontractors (S), providing services to the three key vendors. We interviewed eighteen representatives at the client, as well as the vendor organizations, to identify the specific multivendor challenges that they experience.

Figure 1. Multi-sourcing arrangement under study. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Contractual challenges

Our case study shows the contractual relations between the client and each vendor. Considering the eco-system, we find that the contracts comprise high-level information with regard to a coherent inter-organizational structure, strategy, and plan, as well as the position of each party and their mutual relationships. Moreover, documentation showed that the client set up entry and exit rules on how to deal with new vendors, for example technology partners like Microsoft and Oracle. However, we did not find any detailed information on the set-up and implementation of eco-system entry and exit rules at the client or at the vendors. The absence of such details resulted in fierce discussions about service provisioning between the client and its vendors over time. Hence, the lack of details regarding entry and exit rules hinder parties in creating value.

‘We have to become much more mature to be flexible and change partners regularly in our arrangement. This means that we have to work on the details like specs. This allows us to collaborate better and prevent technical discussions between all parties.’ (Source: Client CIO.)

We did not find information that formal contracts include collaborative agreements and plans between eco-system partners, even though operational services have to be delivered by collaborating, and in other domains competing, vendors. All vendors set up Operational Level Agreements (OLAs) to improve the service performance as IT services are mutually dependent. However, these agreements are informal, and not included in the contracts.

‘Based on an informal agreement with the other vendors we started to collaborate on an operational level. For instance, we shared technical application maintenance information with Vendor 1 to deploy and tune our application with their IT infrastructure.’ (Source: Vendor 3 – Contract and delivery lead.)

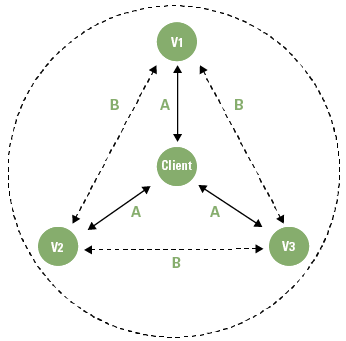

Figure 2 illustrates the contractual relationships within the eco-system. The straight lines (A) represent the formal bi-lateral contracts between the client and its vendors. The dotted lines (B) show the informal operational agreements between the vendors.

Figure 2. Contractual relationships. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Service portfolio challenges

We identified that the client consciously developed a service portfolio blueprint and plan, and allocated the various IT services to the three vendors respectively. The service portfolio plan and the division of services is supported by formal and informal agreements (i.e. contracts and Operational Level Agreements), while clear boundaries and scope are set with regard to who is responsible for service integration tasks. However, we found that on a more operational level the way in which the service portfolio is governed across the eco-system is ambiguous. We observed that the service boundaries of the vendors on a detailed level were overlapping, resulting in various operational disputes. Examples were related to specifying functional requirements, conducting impact analyses, and technical application management. Consequently, as the vendors were reluctant to collaborate with each other, the client experienced a decrease in service performance, and an extension of project lead times, affecting value creation.

‘The client has set up a service portfolio plan that describes the boundaries of each IT domain, but this plan is not sufficient. In fact, the existing plan can be seen as high level with limited details; actually it’s a workflow diagram that lacks concrete tasks that result in service overlaps.’ (Source: Vendor 2 – Contract manager.)

Due to multiple service interdependencies between the vendors, we noticed that service boundary overlap was considered to be a barrier that affected the exchange of information and knowledge, and as such hindered value creation. We found evidence that the vendors under study shared information mutually, as multiple ad hoc meetings were initiated to discuss and solve operational performance issues. This form of collaboration is more dependent on informal operational agreements and trust, which is typical for an eco-system.

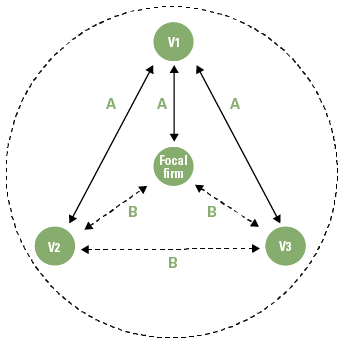

Figure 3 depicts the service portfolio relationships within the eco-system. The straight lines represent the formal service portfolio agreements between the vendors as described in the contracts. The dotted lines represent the informal service portfolio agreements between the vendors and the client.

Figure 3. Service portfolio streams. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Information and knowledge challenges

We found that IT services are partially based on the willingness of the client and vendors to exchange information and knowledge, and that informal arrangements are becoming more apparent. Since applications and IT infrastructure are loosely coupled, the employees of the vendors have to exchange information within the eco-system to ensure the availability and performance of IT services. Due to indistinct service descriptions, which were caused by overlapping service boundaries, and competition between vendors; vendors are unwilling to share technical information with regard to applications and infrastructure. The vendors who are part of the eco-system are also competitors, because they are able to provide comparable services to the client. Hence, vendors focus on safeguarding their Intellectual Properties (IP) to retain their competitive advantage.

‘There are IP issues amongst vendors, even for simple things like sharing information on Unit Testing and end-to-end testing. Due to their competition vendors do not want to share technical information. Moreover, the vendors that act as Service Integrators provide similar types of services in the same market and both act as strong competitors.’ (Source: Client Sourcing Manager 2.)

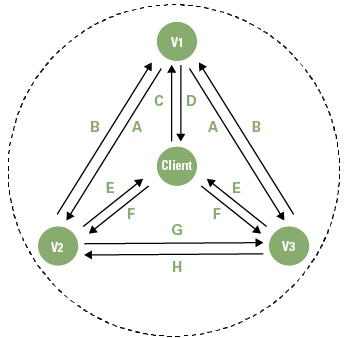

On an operational level, information was exchanged between the client and vendors on an informal basis. We found that employees of V2 and V3 are willing to share information informally to prevent underperformance of their IT services. As V2 and V3 were held responsible by the client for service integration tasks, their employees shared technical information amongst eco-system partners that was related to application work-a-rounds, reporting information, and IT tooling. Actually, no formal processes were set up. Instead employees distributed information when it seemed relevant for the eco-system partners. This approach contributed to building trust between autonomous eco-system partners and reduced the level of operational risk. Figure 4 illustrates that all parties exchange information and knowledge. The straight lines indicate that each party is involved in sending and receiving information and knowledge to support the delivery of IT services.

Figure 4. Information and knowledge exchange. [Click on the image for a larger image]

By reviewing the various perspectives, we are able to identify similarities and distinctions between client and vendors in sharing services and information. Based on the case study, we have summarized some key challenges below:

- the client deliberately focuses on a ‘power’ role to manage the vendors, and as such, competition between vendors is encouraged and this restricts their willingness to exchange services and information;

- due to the partial incompleteness of the contracts and the service portfolio overlap additional information and knowledge has to be exchanged amongst the vendors, which limits their efficiency;

- the limited degree of interaction from the perspective of the client implicates a mistrust towards the vendors and hinders the establishment of a common interest.

Overall, the challenges show that value creation is hindered, because the relationships between the client and vendors are unbalanced. By applying governance mechanisms to the challenges as described above, the client and vendors are able to develop a strategy to overcome these challenges.

Strategy to create value by using an eco-system approach

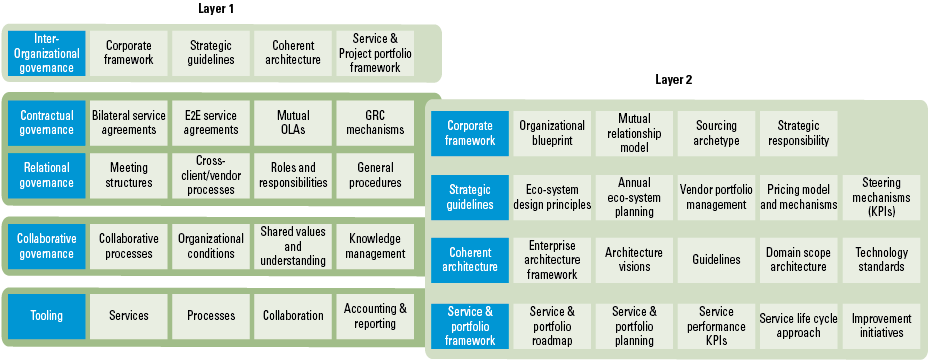

Based on a review of various IT multisourcing arrangements during the past decade, we have developed a reference model to overcome IT multisourcing challenges. The objective of KPMG’s multisourcing reference model is to establish a coherent eco-system that can be governed effectively. As such, clients and vendors may benefit from establishing an environment that is focused on creating value, rather than stimulating competition. KPMG’s IT multisourcing reference model can be used to assess how governance between parties is set up, in order to identify ‘governance blind spots’. The methodology focuses on governing the interdependencies between four essential governance modes, namely: inter-organizational mode, contractual mode, relational mode, and collaborative mode. Each governance mode comprises various attributes that are studied in-depth to reveal their existence, as well as their mutual relationships. Importantly, the reference model can be used to assess the governance between a client and its vendors, and between vendors. As a result, identified governance deficiencies can be repaired, which contributes to achieving a sustainable sourcing performance of all parties over time. The reference model (see Figure 5) consists of multiple layers, in which each governance mode attribute (Layer 1) can be broken down into various building blocks (Layer 2), to specify the details.

Figure 5. KPMG’s multisourcing reference model. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Inter-Organizational governance mode

With regard to the first governance mode ‘Inter-Organizational governance’, the key objective is to determine an inter-organizational structure, to identify the role of each party (client and vendor) in the eco-system. A corporate framework that describes the role of the client and its vendors is helpful to be able to position each party. In addition, strategic guidelines or policies can be established to avoid uncertainty with regard to the role of each vendor. Examples are: setting up clear entry and exit rules for vendors, describing a coherent architecture to guard service boundaries between all vendors, and establishing a service portfolio framework that reflects the eco-system as a whole.

Contractual governance mode

The ‘contractual governance’ mode determines and ensures that contractual aspects and their interdependencies are described in a thorough manner. As a starting point, regular bilateral service agreements between the client and each vendor are described to ensure the provisioning and quality of IT services. In case one or multiple vendors act in the role of service integrator, additional guidelines are required to describe and agree on end-to-end (E2E) service agreements. In practice, this is more difficult compared to single outsourcing arrangements, as multiple vendors are dependent on each other, in which the service integrator has the final service responsibility towards the client. Next, mutual Operational Level Agreements (OLAs) are required to streamline operational tasks between the vendors, for instance in sharing information about workarounds and technical application maintenance tasks. In the end, rules regarding Governance, Risk, and Compliance also need to be setup to ensure that the eco-system as a whole is regulated guided.

Relational governance mode

When addressing the ‘relational governance’ mode, it is important to identify and describe the mutual relationships between all parties. Common activities are setting up a regular meeting structure between a client and each vendor. However, it is also beneficial to implement cross client vendor meetings, since vendors might be interdependent. As such, it is relevant to also exchange vendor-vendor information. This results in the need to create clarity on mutual roles and responsibilities between all parties. An eco-system RACI (Responsibility, Accountability, Consulted, Informed) matrix might help to structure and guard the role of each party. General procedures further guide the exchange of information between the client and vendors, for instance about the replacement of key personnel, invoice mechanisms, complaint management and dispute resolution procedures.

Collaborative governance mode

The ‘collaborative governance’ mode determines and encourages collaboration between parties in order to deliver end-to-end services. Key topics are developing and implementing processes that support collaboration between the client and vendors, creating a culture that is based on sharing information and balancing the power-dependence relationship. Moreover, establishing shared values and understanding may encourage collaboration even further, for example by creating a shared vision and common objectives and commitment. In addition, mechanisms can be developed to exchange information and knowledge, and promote continuous learning and capability development between the eco-system parties. These topics create a ‘what’s in it for us’ way of working, that relates to the philosophy of Vested Outsourcing ([Vita12]).

Tooling

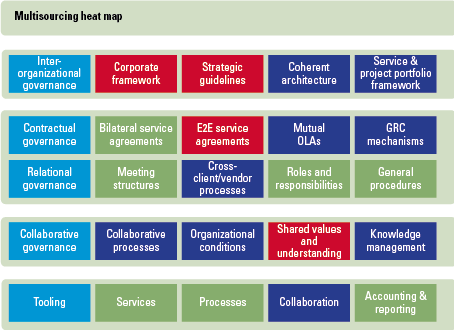

Finally, tooling can be used to support the above-mentioned governance modes effectively. In practice, various solutions are available that streamline mutual activities to increase performance and limit the number of faults or disputes between eco-system parties. For example, tooling is used to support IT services and IT processes ([Oshr15]). Collaborative tools are used to automatically exchange information between the client and vendors, and increase awareness and continuous learning. Accounting and reporting tools can be used to report IT (end-to-end) performance, financial status and invoices, and contractual obligations. Figure 6 illustrates the reference model in the form of a governance heat map that reflects the status of the eco-system.

Figure 6. Reference model illustrated as a governance heat map. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Conclusion

Based on the lessons learned from various IT multisourcing arrangements and the conducted case study, we experienced that a holistic perspective is needed to align single governance modes and create a coherent approach to transform into an eco-system. The benefit of a coherent approach is that clear ‘rules of engagement’ can be defined between all parties that limit service boundary overlap, and increase collaboration by exchanging information and knowledge, which is a prerequisite for value creation. The KPMG IT multisourcing reference model has been applied both in the Netherlands and abroad, and is perceived to be a proven approach to transform an IT multisourcing arrangement into an IT eco-system. By applying the model, clients and vendors may use this strategic instrument to improve their services and create value.

References

[Bapn10] R. Bapna, A. Barua, D. Mani and A. Mehra, Cooperation, Coordination, and Governance in Multisourcing: An Agenda for Analytical and Empirical Research, Information Systems Research, 21(4), 2010, p. 785-795.

[Beul05] E. Beulen, P. Van Fenema and W. Currie, From Application outsourcing to Infrastructure Management: Extending the Offshore Outsourcing Service Portfolio, European Management Journal, 23(2), 2005, p. 133-144.

[Gonz06] R. Gonzalez, J. Gasco, J. Llopis, IS outsourcing: a literature analysis, Information and Management, 43, 2006, p. 821-834.

[Moor93] J.F. Moore, Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition, Harvard Business Review, 1993.

[Oshr15] I. Oshri, J. Kotlarski, L.P. Willcocks, The Handbook of Global Outsourcing and Offshoring, 3rd edition, Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2015.

[Palv10] P.C. Palvia, R.C. King, W. Xia and S.C.J. Palvia, Capability, Quality, and Performance of Offshore IS Vendors: A Theoretical Framework and Empirical Investigation, Decision Science, 41(2), 2010, p. 231-270.

[Plug15] A.G. Plugge and W.A.G.A. Bouwman, Understanding Collaboration in Multisourcing Arrangements: A Social Exchange Perspective, In: I. Oshri, J. Kotlarsky, and L.P. Willcocks (Eds.), Achieving Success and Innovation in Global Sourcing: Perspectives and Practices, LNBIP 236, p. 171-186, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2015.

[Rome11] D. Romero, A. Molina, Collaborative Networked Organisations and Customer Communities: Value Co-Creation and Co-Innovation in the Networking Era, Production Planning and Control, 22(4), 2011, p. 447-472.

[Vita12] K. Vitasek and K. Manrodt, Vested outsourcing: a flexible framework for collaborative outsourcing, Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 5(1), 2012, p. 4-14.