There are numerous tools and systems available that enable organizations to gain control and comply to rules and regulations. Examples of these tools are BWise, MetricStream and SAP Process Control. These tools and systems help companies to document their processes, risks and controls, capture evidence of executed controls, monitor and follow up on issues and report on the compliance status of their organization. Many companies using SAP as their core ERP system tend to choose SAP GRC as their risk and control monitoring system. Therefore, we will focus on SAP Process Control and describe its main capabilities and functionalities, implementation considerations and how custom reporting can be leveraged.

Introduction

In an ever increasing complex and regulated business environment, organizations are faced with challenges on how best to manage internal controls and compliance. Despite the recognition that efficiencies could be gained through a more automated control model, many companies are relying on manual processes. Leading companies recognize the importance and urgency to stay ahead of today’s compliance curve and keep pace with changing regulatory and audit requirements.

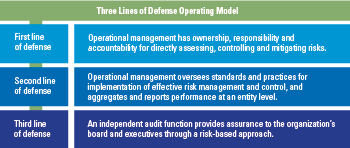

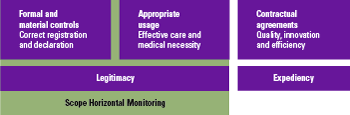

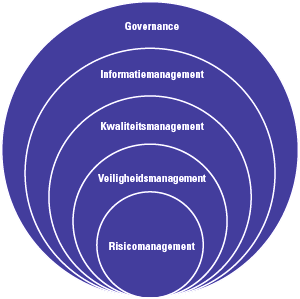

Governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) has become a top executive priority, but many organizations are struggling to manage and control risk effectively today. The ‘three lines of defense’ operating model for managing risk provides a framework that allows organizations to set up their risk and compliance organization. The following lines are defined in the three lines of defense model (see Figure 1):

- the first line is business operations management;

- the second line includes risk management, compliance, security, and legal departments;

- the third line is the independent internal audit function.

Figure 1. Three lines of defense model. [Click on the image for a larger image]

There are numerous tools and systems available in the market that enable organizations to gain control and comply to rules and regulations. Examples of these tools are BWise, MetricStream and SAP Process Control (see [Lamb17] article on trending topics in GRC tools in this Compact edition). These tools and systems help companies to document their processes, risks and controls, capture evidence of executed controls, monitor and follow up on issues and report on the compliance status of their organization. Many companies using SAP as their core ERP system tend to choose SAP GRC as their risk and control monitoring system. Therefore, this article will focus on SAP Process Control and describe its main capabilities and functionalities, implementation considerations and how custom reporting can be leveraged.

What is SAP Process Control?

SAP Process Control (PC) is an enterprise software solution which can be used by organizations to manage their compliance processes more effectively and realize the value of a centralized model.

Data forms, workflows, reminders and escalations, certifications, and the use of interactive reports support members of business process teams, internal control and internal audit to carrying out their individual compliance activities. Process Control provides a centralized controls hub in which testing, certifications and policies, monitoring and documentation can take place.

Process Control is a key part of SAP’s GRC software, sitting alongside SAP Risk Management, which enables an organization to define its enterprise risk and responses to those risks and SAP GRC Access Control, which assists in detecting, remediating, and ultimately preventing access risk violations. Although not a requirement for implementation, Process Control can be integrated with these two modules to provide added value to customers of SAP GRC.

Process Control key functionality

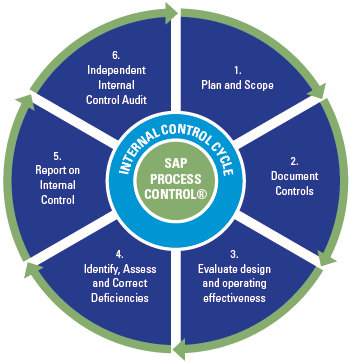

SAP Process Control provides the following core functionalities (see Figure 2):

- Provides documentation of both centralized and local control catalogs, alignment of compliance initiatives and efficient management of risks and controls through workflow functionality.

- Supports scoping through risk assessments and materiality analysis as well as the planning of control testing.

- Supports the design and test of the operating effectiveness of controls with online or offline workflow functionality and consistently registers test evidence and issues found from testing. Control testing can be performed manually, semi-automated and fully automated.

- Enables the documentation of control deficiencies and issues and provides reporting capabilities to track and correct deficiencies (i.e. re-evaluations).

- Leverages sign-off and periodic disclosure survey functionality to formalize management approvals which includes issue tracking and deficiency remediation.

- Allows a full audit-trail and log of performed test steps, including documented sign-offs to allow for an independent control audit.

Figure 2. Core functionalities of SAP Process Control. [Click on the image for a larger image]

In practice, some auditors at organizations using Process Control have leveraged the controls description and evidence in Process Control for their (IT) audit procedures. So far, the risk assessment and materiality analysis functionality in Process Control have not been used for this financial statement audit purpose.

SAP GRC Process Control can also perform continuous control monitoring, including monitoring the segregation of duties and critical risks defined in SAP Access Control. Controls can be monitored at a specified frequency (weekly, monthly, etc.) and results can be automatically sent to appropriate control owners.

Considerations for implementing SAP Process Control

When implementing Process Control there are several areas to focus on, including master data setup and workflow considerations. Automated control setup and reporting are summarized.

Besides these focus areas for SAP Process Control it is also very important to consider the use of SAP Access Control and SAP Risk Management and the integration of the various modules in the GRC suite. When all three modules are set up, there will be shared data and integrated functionalities which may need additional attention during the setup of the system.

Master data setup

Process Control master data has two important components: the organization hierarchy and the control library. When setting up the organization hierarchy there are two key questions that need to be answered:

- What model will be used to define hierarchies and who should be involved? If multiple GRC components are being installed (the organization hierarchy can be shared by Access Control and Risk Management), multiple teams may need to be involved in the setup of the organizations.

- How should the organization report on compliance? This could be on a company code level, line of business, or by region. In some cases, multiple reporting requirements need to be integrated and reflected in the organizational hierarchy. E.g. some organizations require lower level reporting and tend to set up every company code as an organization, whereas other organizations need more high level reporting and set up reporting entities (a group of countries or company codes) as their organizations.

It is important to make decisions around the control framework before loading the control library into Process Control. Here are some aspects to consider:

- In case there are multiple control frameworks in the organization, which one should be loaded to the system? Should they be harmonized or should they be separate? What kind of information is most important and should be included in the system, and which information could be discarded?

- How to test shared service controls? Will a shared service organization be used in the system or are the individual controls tested and documented by control performers from a shared service center?

- All controls need to be assigned to a subprocess, without the subprocesses it is not possible to maintain a control library in Process Control.

- Is there a clear distinction as to which controls are performed in which organizational unit? This is necessary for the control to organization mapping.

- Will it be required to document account groups, financial assertions and risks covered by the control and control objectives? Process Control has master data available for each of these items that can be setup. This is required if scoping is performed in SAP Process Control.

The master data is the foundation of the system. In the situation in which (Master) Data Management is not thought through or set up correctly and according to the company needs, there could be an impact on reporting and efficiency of the functionalities that are used. If framework integration is not performed properly this could even lead to duplicate controls being tested.

Workflow use cases

The second important area of interest during an implementation is around workflow. The first question to ask here is: ‘What does the organization’s compliance process look like, how are controls to be tested, and should this be documented?’, since it makes sense to only implement workflows that will benefit the organization. Furthermore, it is important to bring all the relevant stakeholders together and agree on the owners of the various workflow tasks and which areas can and cannot be customized. It is also important to agree upon the degree of notifications and reminders that are needed. If users get too many emails, the intent of the emails could get lost and users may end up ignoring them.

Once the testing cycles have started and the system starts being used, it is important to have an administrator to monitor all incoming tests and if necessary reroute, close or even delete them from the system. This must be done with the utmost care and should only be performed by experienced Process Control administrators.

Automated controls

SAP Process Control can perform semi and fully automated testing of controls. The SAP GRC module retrieves the settings from the target system and analyses reports or system settings and validates these against set business rules to determine whether the settings comply or not.

When setting up automated controls, there are different types of controls that can be identified: application controls, master data controls and transactional controls. Even though Process Control offers various integration scenarios, the key is to keep it simple upfront and focus on configuration and master data controls to achieve minimum setup difficulty. The different types are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Control types for automation. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The most important integration scenarios to cover these types of controls are:

- The ABAP (Standard SAP Report) integration scenario (e.g. providing control performers with the RSUSR003 Report). The added value of ABAP report controls is the (workflow) support it provides to internal control staff for retrieving the right data from the various SAP systems and delivering it to the appropriate mailbox for further analysis.

- The configurable controls scenario (e.g. check whether tolerance limits are set). The configuration controls are stronger than the other two types, on a daily basis and based on a change log that the customized settings in SAP can be verified.

- The HANA (SAP Advanced analytics platform) integration scenario (e.g. perform advanced analytics to find potential duplicate invoices). The integration with Process Control is to relate the identified exceptions to a control, and assign such controls to the right staff.

While setting up automated controls it is essential that the controls are pre-tested in the acceptance environment and that stakeholders as well as control owners are aware of the potential issues that will be raised as outcomes when controls like these are automatically tested.

Reporting

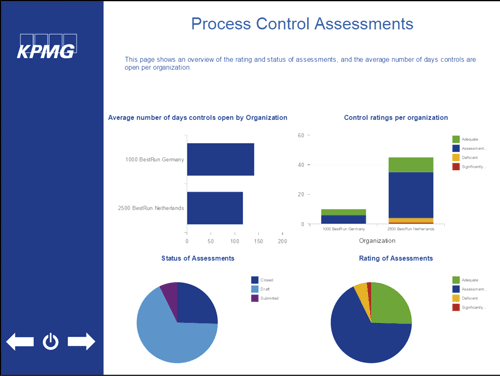

The topic of reporting is often forgotten during Process Control implementations, despite its utmost importance. In order to get most value out of the reporting the key is to define the different audiences and only provide relevant reports to each audience. When all reports are available to everyone, this could become an overkill of reporting possibilities and confuse the end users.

During an implementation of SAP Process Control reporting requirements should be gathered up front so that they can be used as a guideline throughout the project. As mentioned before, the organization structure plays a vital role in the system and will also impact the way reports can be used and visualized.

If the standard reporting capabilities in Process Control are insufficient for an organization’s management reporting (for instance due to tactical information needs), external dashboards could be created based on relevant Process Control tables. In order to do this, technical knowledge of the system and its data model is required.

<<START ARTIKELDEEL DAT ALLEEN IN LANGE ONLINE VERSIE TERECHTKOMT, WELLICHT NIET ALS COMPACT-ARTIKEL]

<<in marge van korte versie op dit punt toevoegen: >> For the longer version of this article, see www.compact.nl. >>

Master data components and considerations

A key differentiator for SAP Process Control is the shared catalog of master data that comes from a multi-compliance framework. SAP Process Control allows companies to manage requirements from different regulations and mandates (SOX, JSOX, 8th EU Directive, GDPR, FCPA, etc.) from one central place. Test results of a control will be applicable for multiple regulations, which reduces the overall test effort which would result in cost savings. Much of the master data can be shared between the various GRC modules: Process Control, Access Control and Risk Management. Some examples for this shared data are organizational data, mitigating controls, risks for SAP Risk Management and SAP Process Control.

Both central master data (applicable to the entire company) and local master data (organization dependent) are necessary to setup:

Central master data

- Organizational Structure

- Risk Library

- Control Objectives

- Account Groups and Assertion

- Central Control Library

- Regulations and Requirement

- Policies

- Indirect Entity-Level Controls

Local master data

- Organization-dependent Subprocesses

- Organization-dependent Control

- Organization-dependent Policies

- Organization-dependent Indirect Entity-Level Controls

Organizations

The organization structure is the central common master data entity in SAP GRC. The organization structure can be shared among SAP Risk Management, SAP Process Control and SAP Access Control. Often the structure of the company codes in SAP can be used, where company codes are grouped in countries. However, sometimes the reporting entities are not similar to company codes or structures and alternative structures need to be developed, such as by functional area or business unit.

CAUTION – Organization Structure Setup

Companies need to determine how they will arrange their organization hierarchy. It is important that this structure is well considered before building this master data in SAP PC. Consider the following:

- What model will be used to define hierarchies and who should be involved? If multiple GRC components are being installed (the organization hierarchy is shared by Access Control and Risk Management), multiple teams might need to be involved in the setup of the organizations.

- Additionally the key question is how the organization will report on compliance. Is that on a company code level, a line of business level or perhaps a regional level? In some cases multiple of these reporting requirements need to be adhered to, and need to be reflected in the organizational hierarchy.

Organizations can be grouped as nodes in an organization hierarchy, with sub-nodes such as legal entities, plans, profit centers or divisions.

Central process hierarchy

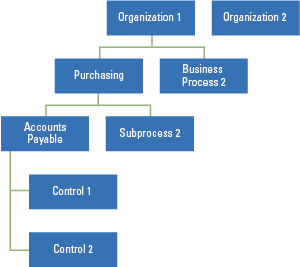

Defining processes and subprocesses is also an essential step in master data setup. A process refers to a set of activities relating to a specific function in an organization’s operations, such as purchasing. A subprocess refers to a subset of activities within a business process, such as accounts payable within purchasing. Controls are created under subprocesses and are assigned to compliance areas/regulations. A process node can have any level of nested child process nodes, or a single child level of a subprocess. A subprocess can only have control as a child (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Process hierarchy. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The entire business process hierarchy exists mainly to provide context for the control; while the amount of information that can be maintained at the process and subprocess level is limited. The control is the main SAP Process Control master data type through which much of SAP Process Control functionality is presented.

TIP – Master data creation and customizations

There are many dependencies when it comes to Process Control master data. It is recommended to create the objects in the following order:

- Regulations;

- Control Objectives and Risks;

- Process, Subprocesses and Controls;

- Organizations.

Notes:

- Once all the objects are created, master data assignments can be performed, such as assigning subprocesses to organizations.

- Multiple organizational views can be created if separate master data is desired for Access Control, Process Control or Risk Management.

- Field based configuration can be customized to hide field and/or allow ‘local’ changes to a field. Attribute values can also be edited, which results in changed contents of fields in the controls screen.

CAUTION – Audit trail

It is important to note that nearly all of SAP Process Control master data has effective dates (from and to). This helps to drive alignment with regulations, organizational structures, business process models, controls, monitoring rules, test plans, assessments, and surveys that change over time.

TIP – Master data upload

The MDUG tool in SAP Process Control allows administrators to mass upload data for PC Risk Management from a MS Excel Sheet. This enables customers to capture all of their master data in a single place, which makes reviews and signoffs more convenient.

Note: the MDUG template can often take multiple reiterations in order to upload without errors as SAP checks for multiple items, such as mandatory fields. Refer to the SLG1 logs for insight into upload errors.

Workflow capabilities in SAP Process Control

Surveys and test plans

When workflows are to be sent out, there need to be surveys or test plans that guide the user in performing their task.

Surveys contain a number of questions which need to be answered by the user in order to complete the task. The survey questions are set up by the organization itself and can have multiple answer types. The following answer types are supported:

- Rating: this provides rating buttons from 1 to 5;

- Yes/No/NA;

- Choice: you can define your own answers;

- Text: free text field.

The surveys can be configured in a way where comments are required once an answer is selected. The surveys need to be setup for each workflow (e.g. one for self-assessments, one for control design assessments, etc). When the workflow is planned the survey that needs to be used is selected. Based on this, the workflow task (both online and offline) will be created with questions from the selected survey.

Test plans are slightly more elaborate and need to be created for each control. The test plan includes steps that need to be performed in order to perform the independent test, including the sample size and sampling method. The test plans need to be assigned to controls in the business process hierarchy. When a test of an effectiveness workflow is sent to the users, the test plan assigned to the control is represented in the task. The user that performs the test plan then needs to execute and pass or fail each step. When this is done a final pass or fail needs to be selected for the entire test task.

TIP – Test plan usage

If test plans are maintained for each control: they also need to be maintained in the system for each control e.g. if there are 300 controls, there will also be 300 test plans, all with multiple steps. It can be beneficial to create one generic test plan with the possibility to add control specific attachments.

A manual control performance plan also needs to be maintained for each control for the manual control performance workflow. This allows the control performance steps to be assigned to multiple testers, enabling shared ownership for performing controls and documenting evidence.

Available workflows

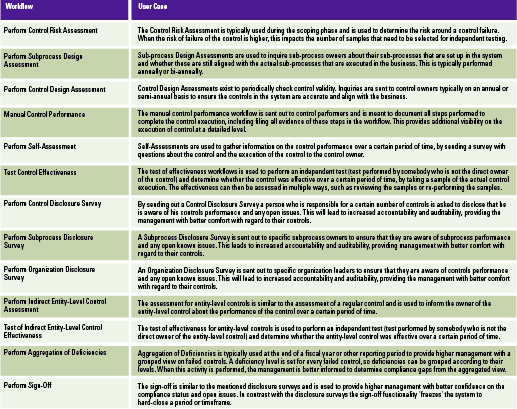

To support organizations in carrying out their compliance with regulations and frameworks, Process Control provides several default workflows to capture execution of control assessments and control tests. Table 1 shows the various workflows that are available and how they can be used and customized within a business context.

Table 1. Available workflows and corresponding user cases. [Click on the image for a larger image]

TIP – Use of workflow types

Although SAP Process Control contains many different assessment and test types, it is recommended to carefully review the user case for the different workflows in the organization, and not to implement workflows that will never be used.

For all of the workflows where an effectiveness rating is provided there is a built in check which forces the user to create an issue in case the control assessment or test or sub-process assessment failed. When the issue is created, an issue workflow is automatically started. The issue workflow can be leveraged to follow up on the issue and take corrective and preventive actions or start a remediation workflow.

Workflow setup options

As not every organization has exactly the same compliance monitoring processes, SAP Process Control can be customized to better fit the needs of an organization. For all assessment and test workflows a review step can be added in the workflow. The system can also be set up in such a manner that a review step is automatically skipped, based on the rating of the assessment or test (e.g. when the control assessment or test was rated effective the review step will be skipped).

TIP – Different flows in different entities

When the global system is set up to trigger a review for every task performed, but this is not mandatory for all entities within the company, there is a setting in the master data which allows to defer from the standard workflow per organization or per subprocess.

To ensure that stakeholders are aware of the tasks that they need to perform, the system can send automatic notifications, reminders and escalations via email. A notification will be sent to the user that needs to perform a task when the task is created, a reminder is sent to the user some time before the deadline and an escalation is sent to the accountable person just before, or even slightly after the deadline.

CAUTION – There should not be an overkill of email

When notifications, reminders and escalations are all active, a lot of email will be generated. When too many email are generated, it becomes an overkill and people will get annoyed and set up email rules to automatically reroute or even delete the email from SAP Process Control out of their inbox.

To make the workflows more accessible, SAP Process Control also enables offline processing, making use of Adobe Smart forms. By making use of this functionality, all workflow tasks that are normally performed in the Process Control system can now be performed using interactive PDF files and regular email. When making use of interactive PDF forms, it is really important to monitor the system upon creation of the PDF’s, and that PDF’s are correctly sent out.

TIP – Monitoring the incoming tasks

If the offline Adobe forms are used, it may be beneficial to monitor the process more closely. The following transactions can be helpful:

- ST22: to troubleshoot short dumps;

- SLG1: to identify possible inbound emails that have not been correctly processed;

- SOST: to monitor outbound and inbound email messages.

Monitoring workflows

When workflows are sent out to the internal control community, it is vital to monitor whether workflows are also closed before the set deadline. SAP Process Control provides a standard functionality which shows an overview of all open tasks, which user currently needs to take action on the tasks and whether the task is overdue or not. This overview can be found in the ‘planner monitor’.

When workflow tasks are stuck, it may be necessary to push, reroute or even delete existing workflow tasks.

CAUTION – Workflow administration

Deleting existing workflows must be performed with utmost care. If this is not done properly, workflow tasks could be damaged, or the information of other or all workflows could be removed. When not performed correctly, there can be a large impact on compliance evidence.

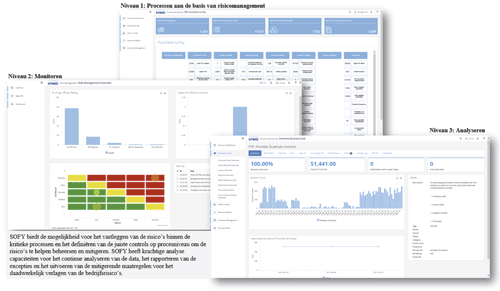

Continuous control monitoring

SAP provides functionality to automatically test controls in SAP or in other SAP applications. This can provide great value to organizations and increase efficiencies around control testing. Automated controls often receive a high level of interest from auditors. If they are able to rely on automated controls, there is a potential that their workload will significantly decrease. There are different kinds of integration scenarios possible. In this article, we will discuss the following:

- the ABAP integration scenario;

- the configurable controls scenario;

- the HANA integration scenario.

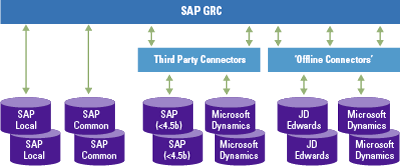

Continuous control monitoring is set up by connecting the SAP GRC system to other SAP and non-SAP systems. For SAP systems a RFC connection can be leveraged and for non-SAP systems a special third-party connector or an offline connector (with flat files) is necessary. An example of this is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Connection types. [Click on the image for a larger image]

TIP – Automated monitoring requirements

In order to allow automated monitoring in SAP systems, the relevant SAP plugins (GRCFND_A and GRCPIERP) need to be installed in the target SAP system. Additionally a RFC connection needs to be created and a user with the proper authorizations should be available.

Once GRC is connected to other systems, data sources can be created in Process Control. When creating a data source in SAP Process Control, it is possible to link up to five tables together. In order to make use of the programmed or ABAP report scenario, a program or ABAP report needs to be set up for consumption in the SAP target system.

Caution – Automated controls: ABAP reports

In the case of the ABAP integration scenarios, keep in mind that the ABAP program that needs to be run, needs to be registered in the ABAP Source system with its variant. The variant can be used to make distinctions between organizational entities in SAP. In some cases, additional variants need to be created as part of a SAP PC implementation.

When setting up configurable controls for SAP systems a connection is made to the target system to gather data directly from tables. When the data source has been created (e.g. connection to T001 table) a business rule needs to be set up in SAP Process Control. In the business rule the logic is provided for the system to determine whether values found in the data source are in line with the control (effective) or are not correctly set (ineffective). Based on this logic the system is able to automatically test controls, e.g. when the company code in table T001 is not set to productive (field XPROD equals X), then the control fails.

TIP – Automated monitoring

A configurable control with a daily frequency only checks a certain value once a day. If people know at what time the value is checked, they can still get past the control by changing the value just before and just after the check is done. To prevent this a change log check can be set up. The change log check is similar to a normal configuration control, but provides the changes to the value over a set period of time.

By doing both the regular value check and the change log check it is ensured that the control is effective and has been effective during a set period. This is often the confidence that auditors are interested in.

Many organizations want to make use of the automated controls functionality to monitor transactional or master data controls. However, SAP process control can particularly be used to monitor and test the controls that have actually been implemented in the SAP application itself, so-called application controls. The SAP configurable control functionality can be used for this by performing blank checks (no data has been maintained for specific fields), value checks (values below or above certain thresholds) and change log checks. It is not easy to check for duplicate values within a data source.

TIP – Automated monitoring

A change log check is possible when the change logs on tables have been activated and when the specific table has been flagged to log changes. The change log on a table can be switched on in the target systems via transaction code SE15.

In some cases a combination of different kinds of controls can be used to monitor the actual implementation of the control in the application (required fields within vendor master data) and the effectiveness of the control by monitoring actual data in the system (identifying where required fields have not been populated within master data).

CAUTION – Configurable controls monitoring: what is the real control?

The automated control functionality supports the testing of controls, but it is important to understand what the actual control is. A useful example is the duplicate invoice check. There are multiple settings required in order to enable the duplicate invoice check. These settings are:

- the duplicate vendor check in vendor master data (set as a required field LFA1);

- the warning message that a duplicate invoice has been posted (SAP Configuration – Change Message Control);

- the setting that the systems need to check on additional fields (transaction code OMRDC).

There are actually three controls that are required to prevent duplicate invoices from being posted. However, the vendor account number is always taken into account in these checks. Nonetheless, most companies still have many duplicate vendor master data records or make use of one time vendors, which would allow the possibility to post a duplicate invoice Iine in the system (or typos made in the actual posting reference number).

A new upcoming solution for control automation is the HANA integration scenario. When there is a connection from the SAP HANA System to the SAP Process Control system, data sources can be set up against SAP HANA calculation view. When this connection is in place a whole new level of analytics and exception reporting can be done with SAP Process Control, by leveraging the powerful and advanced analytical capabilities of SAP HANA.

TIP – HANA integration

SAP advises the use of scripted calculation views in SAP HANA to connect to SAP Process Control, even though both scripted and graphical views can be used.

Note: not all field types are supported in SAP Process Control, e.g. timestamp fields are not supported.

Reporting and dashboarding

Throughout the year, and especially at the end of a compliance cycle, every organization wants to know how they stand against their controls. Thankfully, SAP Process Control comes with many different reports that can help organizations see where they stand. In this section, the most relevant reports for each section are described and the possibilities of customized dashboards are explained.

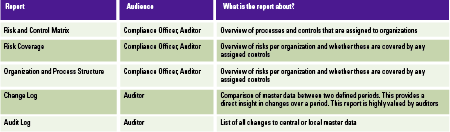

Master data reports

Reports in the master data section are mostly used to check the integrity and completeness of the master data that has been set up. All changes to master data are automatically captured and can also be reported. The reports are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Master data reports. [Click on the image for a larger image]

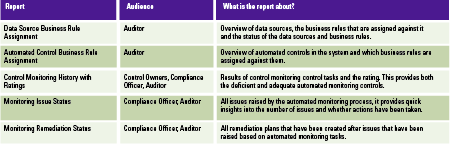

Automated control reports

Automated controls often receive a high level of interest from auditors. If they are able to rely on automated controls, there is a potential that their workload will significantly decrease. The reports in Table 3 can be used by auditors.

Table 3. Automated control reports. [Click on the image for a larger image]

TIP – Changes to business rules

To report on changes to business rules, the ‘Audit Log’ report in the master data section can be used to report only on business rules. This shows all changes to business rules over the selected period.

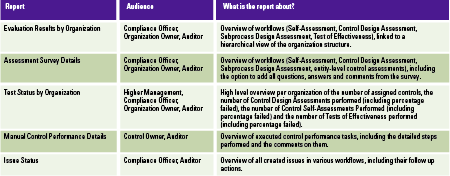

Workflow-related reports

The workflow-related reports are used to show the actual compliance status and progress. In the end, compliance is based on the number of controls that are assessed or tested with a positive rating. The reports that provide insights for this are located in the ‘Assessments’ section of the application. The reports in Table 4 are of interest.

Table 4. Workflow-related reports. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Dashboarding

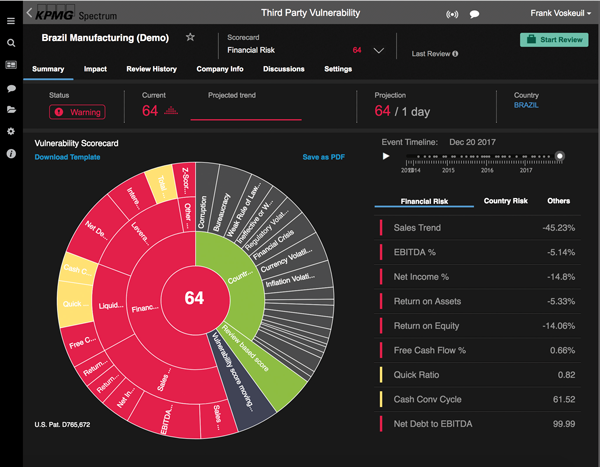

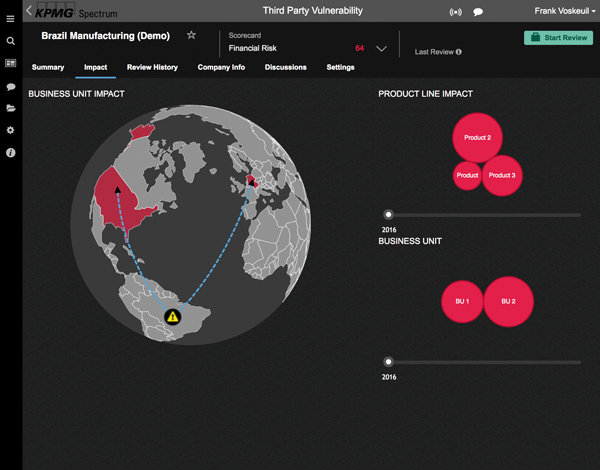

By default, SAP Process Control provides a number of standard dashboard reports. Even though this dashboard can show results for several workflow types (e.g. Assessments, Tests) and even subtypes (e.g. Control Design Assessment, Self-Assessment), its functionality is limited and does not provide proper information for senior management.

Additionally, SAP Process Control now provides functionalities called ‘side panel’ and ‘entry page’. When the side panel is activated, an additional panel is opened, for instance next to the organization structure. Upon selecting an organization, the side panel will show a small dashboard with assessment or test details and issue details for the controls in that organization. Such a feature can be really useful for end users navigating the system. The entry page can be set up per role and can be used to create an entry page with relevant insights into compliance status, status of control assessments, control tests and issues. This entry page can be customized as part of the implementation.

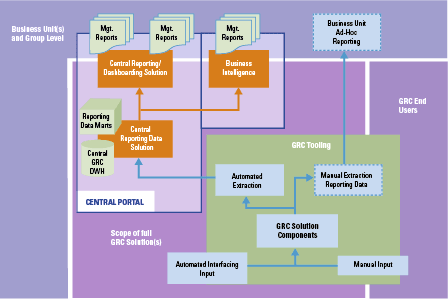

Custom dashboards can also be developed based on data from the system. When creating custom dashboards, the following aspects must be carefully considered:

- Data extraction from (other) systems can be performed in multiple ways (e.g. manual extraction, replication to a HANA system).

- The data must be modeled, so it can be leveraged for a dashboard (there is logic that needs to be applied).

- Organizations must define their own KPIs. Without proper KPIs, the value gained from the dashboards is limited.

- Authorizations are different in dashboards: system authorizations are not automatically captured and applied. E.g. if a user is authorized to only display controls for one organization in the GRC system, then this will not be automatically captured in a dashboard as well. This may require separate dashboards or advanced authorizations for the dashboard if this is possible.

TIP – Relevant tables

The master data in SAP Process Control is captured in HRP* tables (e.g. all object names are stored in HRP1000, control details are stored in HRP5304). Other information, such as workflow information, is mainly stored in tables starting with GRPC* (e.g. GRPCCASEAS contains information about assessment workflows).

When custom dashboards are created, organizations are free to set up the reporting according to their own interest and level of detail. It is often easier to gain higher level insights and compare different parts of the organization using custom dashboards. Figure 6 shows a possible custom dashboard.

Figure 6. Dashboard example. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Conclusion

In this article, we have emphasized the importance of making the right choices when implementing SAP Process Control. For the master data, it is critical to focus on establishing the right organizational structure and integrating multiple control frameworks. For workflows, it is very important to determine the use cases and really integrate the organization’s way of working into the system capabilities. For reporting, it is all about requirements and determining the right reports for the right audience. Finally, for control automation, it needs to be emphasized that SAP Process Control is not another data analytics tool, but a controls monitoring tool. Therefore, the focus should be on configuration settings. By considering the cautions and applying our suggestions, which are included in the online version of this article, SAP Process Control can be a useful solution to help organizations achieve their compliance goals.

Reference

[Lamb17] G. Lamberiks, S. Wouterse and I. de Wit, Trending topics in GRC tools, Compact 2017/3.