Current measures for Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery are not fit for (future) purpose. Most of these measures are focused on old school natural disasters, physical threats, and “micro” operational IT issues. They are not prepared to deal with rapid spreading, large scale and destructive cyber disasters, such as virus outbreaks. Something we have witnessed many times in recent years and the digital threats have only evolved faster and very likely will continue to do so. The world has changed in the face of digital transformations and hyper connectivity. The approach to survive these rapid, destructive, and wide-scale incidents (one could compare these to human pandemic-style events) needs to change as well.

Introduction

New problems often can’t be solved by old solutions. That’s why we need to rethink the concept of cybersecurity in a hyper-connected digital reality when it comes to surviving extreme scenarios, such as rapid spreading and destructive cyberattacks. Large multinational corporations that play in the proverbial Champions League of hyper-connected business need state-of-the-art preparations to optimize chances of survival when serious “shit hits the fan”. This goes (far) beyond conventional Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery. Taking this topic seriously requires unorthodox thinking and doing. Let’s step outside the box and prepare for survival.

For the sake of reasoning, let’s assume you are comfortable with the cyber capabilities of your organization. But what if your organization has to deal with a serious attack similar or worse to the infamous NotPetya attack that took place on 27 June 2017. That day, NotPetya halted Maersk’s global operations for multiple weeks due to the fact it destroyed nearly all servers and endpoints, costing the transport, logistics and energy conglomerate at least 300 million dollars of direct costs related to outage and recovery, let alone the indirect costs. This surely is not a standalone incident, nor was it the largest damage. Estimates about the combined damage are in the range of 20 billion dollars on macro level, and up to 800 million dollars for a single pharmaceutical in the USA.

Now here’s a question for you:

How long would it take you to shut down vital parts of your IT landscape to make sure that malware cannot spread any further and to make sure that – at least most of – the crown jewels of the company will be saved to jumpstart operations after the attack?

Would you be able to do so in a day? In a couple of hours perhaps? Half an hour? Would you be able to obtain all the mandated approvals and if so, the corresponding actions in such a short time?

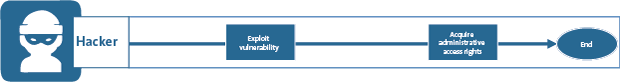

The confronting reality is that NotPetya distributed itself across entire organizations in less than 8 minutes from East to West, from North to South. It was spreading much faster than at first noticed. As said, many others were affected that day, in hindsight tens of thousands of companies were hit by the attack. The consequence: human control over these kinds of pandemic cyber events are simply no longer effective; we need to automate both our protection as well as our response capabilities.

This is one of the key arguments for a radical new approach. The key topic in this article is not how to build the most effective and efficient framework for cyber security, it’s what your organization is capable of in case of a destructive cyber-attack.

One could use the analogy of a pandemic human virus to grasp the impact. When Corona hit China, there was uncertainty on the impact, but at least most of us realized how impactful it could be. We should think about cyber incidents in the same way. The stakes are high in terms of losing trust and financial robustness when your infrastructure and data are gone for weeks (or even forever).

It’s clear that we need disruptive thinking to deal with the next wave of sophisticated cyber-attacks.

Anatomy of cyber security in the digital reality

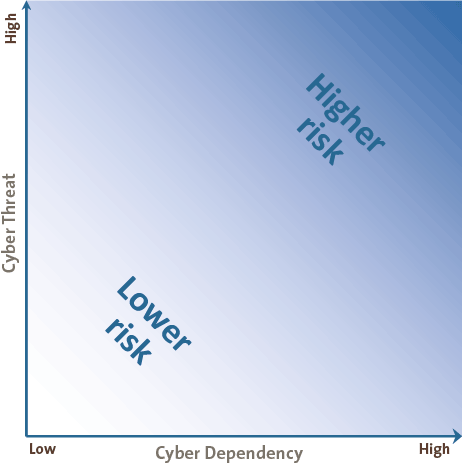

Organizations operate in a so-called VUCA world, a Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous world. The capabilities to succeed in such a world have changed dramatically, and this is certainly the case in the domain of cybersecurity.

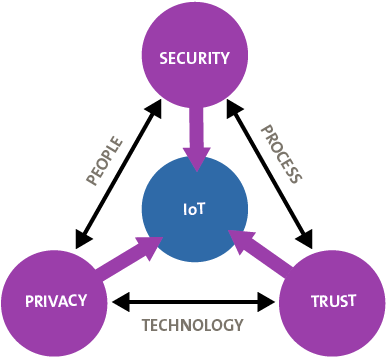

One of the challenges is that we live in a world of hyper-connected ecosystems. The Internet of Things grows at an astonishing pace. Everything connects with everything, and it doesn’t stop in the digital world; it is also strongly tied to our physical world. Physical infrastructures ranging from traffic lights, production facilities, trains and many others are not just physical assets: they have an underlying digital backbone. A growing interconnectedness of the world also causes exponential growth of the impact of breaches or failures – like a “ripple effect”.

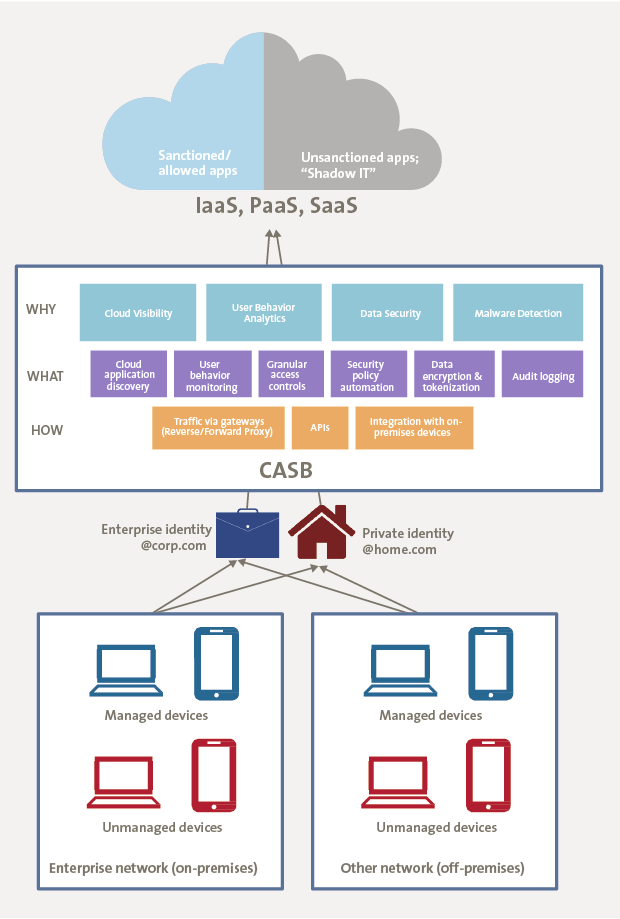

Despite improvements in software security, system hardening, security awareness, and incident detection/response, the attack surface of large organizations is expanding. This is mainly due to system and service interdependencies and the increasing reliance of business on IT services, including cloud, business managed services (self-procured SaaS), and interconnections with multiple domains and supply chains.

Another important factor is the fact that the effectiveness of attacks by perpetrators is enhanced and accelerated by increased specialization and toolchain availability. Added to that are advanced capabilities of organized cybercrime and nation state activity. An example of this is the fact that WannaCry utilized a weaponized NSA tool made publicly available due to a hack or nation state leakage a few months earlier. The devastating results are still observable around the world.

To conclude, business reliance on digital assets grows day by day. A massively disruptive event threatens the sheer existence of an organization given its reliance on IT assets. Firmware level flaws, like Meltdown/Spectre, can affect a very extended set of assets (i.e. motherboards, hard drives, CPUs, etc.) and disturb a target base that can be as wide as the entire global infrastructure.

The brutal – and somewhat inconvenient – truth is that current measures for Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery are not fit for (future) purpose. Most of these measures are focused on “old-school” natural disasters, physical threats, and “micro” IT issues. They are not prepared to deal with large scale cyber disasters. Additionally, the world has changed dramatically in the face of digital transformations with Cloud, Ecosystems and hyper connectivity.

Enterprise-wide Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery has fallen off the radar. Leaders should put it back in focus, updated to match the current world, and with an eye for the potential next wave of unpredictable cyberattacks. Attacks that most likely will be stronger, faster and deeper.

This is not about you?

Many organizations have stepped up efforts in the domain of Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery. They may argue that the aforementioned conclusions are not valid for them. Let’s briefly analyze if this holds true.

“We have active-active data centers in place.”

Many organizations have active-active clusters (mirroring), a set-up with two or more hardware systems that actively run the identical platform/systems/data at mirror sites simultaneously. However, this is not at all a guarantee for continued operations, as viruses spread across multiple mirrored systems in an instant, as that is what they are designed for to do.

“We use backup tapes.”

Are you sure? Backup tapes are not that safe either. Not only because the sheer volume of digital activities simply makes it impossible to use tapes, but also because the tapes that were recovered resulted in the larger hacks in history, as they were already infected. It is often very hard to find the point where the infection / hacker is not present. In addition, a key point here is that most “tape” backups are nowadays put on disks, as part of the storage solutions. Of course mirrored as well, but that doesn’t help you.

“We have stringent contractual / service level agreement clauses.”

Legally, you may have covered it well in contracts with service providers. But how important is the paperwork when it comes to living up the promises in case of a pandemic order? When an entire region goes down, which organizations will have priority? In many cases, vital infrastructures like fuel supply, power, emergency services and banking will have priority over your urgent needs.

“We have data ownership.”

Data ownership is only relevant when partners are still active in business. In case of large disasters, they could face bankruptcy or get suspension of payment decision. All assets may then be locked, and access denied. A horror story? A fact of life, as it already happening at several organizations who were the legitimate and legally confirmed owners of data but didn’t get access (even not via court).

Next level survival management

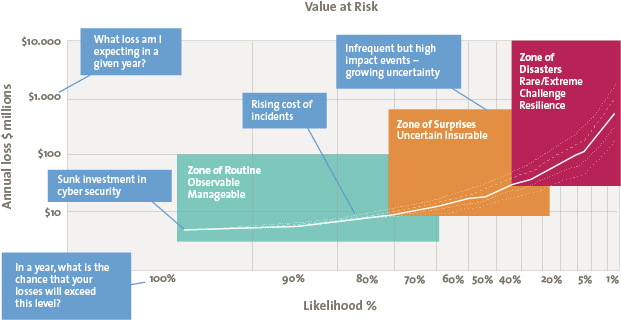

Research from recognized cyberthreat and intelligence organizations such as Verizon, Mandiant and ISF, indicate that the next wave of cyberattacks will likely be more sophisticated. Attackers will be better equipped, more intelligent and will recycle successful methods that were successfully applied earlier, a trend which was also recently reported in the Europol EC3 cyber update 2019 ([Euro19]). As it has been a while since there was a large global cyberattack (2017 for instance), we should expect something big to happen. The typical question in the cyberworld is not if it will happen; rather when and where it will happen.

It is a fact that there are no waterproof solutions to prevent us from these attacks as whatever you do, perpetrators will always find ways. The least we can and should do is raise the stakes in survival management. This calls for disruptive thinking. Next, we will present four “outside the box” thoughts on survival management.

1 Next level last resort preparations

Organizations need to have a clear view on what they actually need to restart operations after a disaster. In other words, they need to know their crown jewels and which parts of their digital ecosystem are vital for being and staying in business. This may be a basic, but often neglected topic. This is actually why it needs to be on the agenda of the board, top down, it should not to be dealt with solely by IT.

Again, it should be noted that the analysis is to understand what is required to restart the company after the cyberattack. It is not the intention to “save” everything, this is all about survival preparation and not “regular” business continuity.

With this top-down, business-driven analysis, organizations can step up efforts in multiple domains to increase the chances of survival.

One is the concept of Infrastructure as Code for vital parts (see box for a definition). We’ve witnessed a tremendous rise in the use of agile methods to develop new systems and applications in the past decade. However, the deployment phase is often still quite traditional and slow. Technically, it is feasible to deploy systems and applications on new infrastructures very quickly (to rebuild the company). Infrastructure as code uses a descriptive model to do so. In the simplest analogy, one could say that it is an apple pie recipe. You know the ingredients, the steps to be taken and the tools you need. Therefore, the best way to guarantee future apple pies is not to store the pies, but to keep the recipe safely.

Infrastructure as Code, or programmable infrastructure, means writing code (which can be done using a high-level language or any descriptive language) to manage configurations and automate provisioning of infrastructure in addition to deployments. This is not simply about writing scripts, is also involves using tested and proven software development practices that are already being used in application development. For example: version control, testing, small deployments, use of design patterns etc. In short, this means you write code to provision and manage your server, in addition to automating processes.

Source: [Sita16]

Another is the concept of Islands of Recovery. This concept is not about what is needed to guarantee a full-scale continuity of the business, but what is required in order to avoid shutting down businesses completely due to complete loss of infrastructure and data. As a plus, the Islands of Recovery can also support businesses at regional level during incidents. To achieve this, we need to carefully consider how these islands are connected and secured.

Examples of protection measures for the islands of recovery include:

- Full segregation from the production environment;

- Mono-directional traffic for system/data updates (i.e. via network diodes);

- System hardening that “ignores” system functionality requirements; nobody changes the functioning of the survival mechanism, not even the business owners. Self-survival is key and established by the system itself (“think it as a protection mechanism against humanity”)

- Preservation of a reduced set of required users;

- Preservation of “vital” data;

- Redundancy of external service providers; What is normal in the “traditional” world – having multiple bank accounts or credit cards – should be the norm in digital as well.

- Hardware/software and IT administrator diversity.

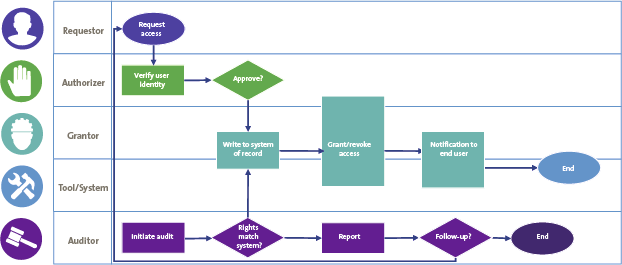

2 Rapid isolation of zones

In the physical world, segmentation is a proven concept to limit the impact of floods or other disasters. The digital world can learn from this by thinking in blast zones1 like rapidly shutting down zones to prevent further spread of problems. Shutting down zones very fast would limit the impact of a problem in a very effective way. When a problem becomes manifest in a London office, local measures could be taken first. Should this be too late, the entire UK infrastructure could be taken down. Only when this measure is too late, would we need to shut down other country infrastructures. One could compare it with isolating a faulty circuit. In the physical world, we wouldn’t accept it if a problem in one of the circuits in a building would cause a shutdown of het whole building. Likewise, we shouldn’t accept that a single problem in an IT system should cause all software to collapse. Shutting down blast zones can prevent this from happening, when applied extremely fast and without hesitation. To be clear: only automation (in control) by computers can do this.

Furthermore, existing threat detection mechanisms have limitations in identifying threats in a timely manner (where timely is in the order of a few seconds – max a minute on a global scale). In this domain, we can use the analogy of the canaries in the coal mine to improve response actions. Miners would carry down caged canaries into the mine tunnels with them. In case of dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide or H2S, the gases would kill the canary before killing the miners. This would mean immediate escaping via the tunnels and potentially drop barriers. As a similar approach, we can implement digital canaries in systems. If organizations compartmentalize resources at high speed (that is including the decision to do so; hence highly automated, machine powered, AI …) they can protect themselves against serious issues. One could place digital canaries (a file, a process, etc.) on several servers and monitor if these files or processes are accessed, modified or deleted (while they are normally not touched). By doing so, organizations will get early warnings on anomalies and with that get early warnings on potential threats.

3 Radical testing

Organizations have often implemented a multitude of measures to deal with disturbance of systems. However, when it comes to testing if the fall-back scenarios and other measures actually work, they are very cautious and only controlled tests are performed (if at all, as many organizations do only predominantly paper-based exercises once a year, as a compliance tick mark). This must change. The automated (at any time) shut-down of random servers and services should be the new normal to test if measures are fit for purpose. Organizations should not be afraid of this type of vigorous testing, even if this upsets business managers. It’s a matter of being bold and just doing it without any dialogue. Only by experimenting with disturbed (distributed) systems, can we build confidence in the infrastructure’s robustness to withstand turbulent conditions.

4 Don’t forget the offline world

Storing vital data on paper? Of course, in most cases, this is not a viable option given the volume of data, but it still happens as backup. However, let’s recall that we are talking about the minimal needs for survival and organizations should therefore consider if there is a minimum set of information that should be kept in safe zones on paper. This information could be the bare minimum to get operations back in business when disaster strikes. The nature of this information strongly depends on the organization and should be tailored to the nature of its operations. It may sound like an extremely simple and old-fashioned measure, but nonetheless an often overlooked and indispensable measure.

Conclusion

Experts agree that the next wave of cyberattacks will be unprecedented in sophistication. This means that current measures will probably not be able to preserve continued business or even minimal operations. For too long, organizations, frequently led by their advisors, have relied on old-fashioned BC/DR measures.

It’s actually very probable that malware is already present behind the scenes and will “ignite” in the (near) future. Leaders should be aware and should be openminded to rethink how they deal with cyber disasters. Extreme response speed and vigor is essential. Some organizations – mostly the generation that was “digitally born in the cloud” – excel in this area. Others can’t keep up and some already point out that their infrastructure is not suited for this new era. This may be an understandable plea. But it can never be an excuse.

Notes

- Also known as “hazardous areas”.

References

[Euro19] European Cybercrime Centre (EC3) (2019). Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.europol.europa.eu/iocta-report

[Sita16] Sitakange, J. (2016, March 14). Infrastructure as Code: A Reason to Smile. Retrieved from: https://www.thoughtworks.com/insights/blog/infrastructure-code-reason-smile

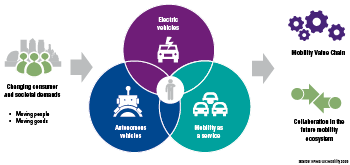

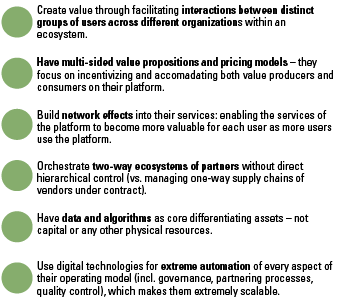

Connected – Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, & Snapchat

Connected – Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, & Snapchat Conscious – socially, ethically, & environmentally aware

Conscious – socially, ethically, & environmentally aware Empowered – many outlets to express their opinion

Empowered – many outlets to express their opinion Individual – expect a personalized experience

Individual – expect a personalized experience Vulnerable – more exposed to risk

Vulnerable – more exposed to risk Informed – unlimited information at their fingertips & are constantly looking for more

Informed – unlimited information at their fingertips & are constantly looking for more