This article provides a review of the key trends and changes in the cyber crime landscape, recognizing that cyber criminals are now ruthless and rational criminal entrepreneurs supported by a vibrant black market in attack tools and techniques, and crime as a service model. The changing threat demands a new approach to cyber security which focuses on layered defences, detection and rapid response, agility in our security approaches, community sharing of threat intelligence, and a new partnership between government and industry around active defence.

Introduction

The term hacker brings with it images of teenagers hunched over keyboards in bedrooms taking on the might of government and major corporations. But does this image really represent the reality of the cyber crime threat, and does the word “hacker” get in the way of thinking about how we deal with the cyber threat?

The reality is often very different. Cyber crime has become a major industry with some estimates ([CSIS14]) suggesting that the impact on our global economy exceeds $400 billion a year. Gartner ([Gart16]) suggests that we spend over $94 billion to secure our systems against these cyber attacks.

Crime always follows money – and the money is now in cyberspace. According to the Bank for International Settlements ([BIS13]) our electronic markets transact over $5,000 billion of foreign exchange transactions in the space of just one day, while eMarketer ([eMar16]) suggests we spent over $1.7 trillion on e-retail in 2015 – a figure expected to double by 2019.

Unsurprisingly cyber criminals have become businessmen. Their business is exploiting access to computers for financial gain. In doing so they show a ruthless and rational entrepreneurial approach.

Think about the landscape from the perspective of the cyber criminal, rather than focusing on the technical attacks themselves. In this article, I provide a structured way of looking at the cyber crime landscape, picking up on key threat trends and drivers, breaking cyber crime down into three main categories of attack: commodity, tailored and high-end.

Next, I look at the implications for our approach to cyber security, considering how we need to change and adapt our defences to counter these emerging threats with an increased emphasis on detection and response, community action and in future industry/government partnerships around active defence.

Commodity Attacks – Playing the Numbers Game

The first category of attack is indiscriminate. It relies on the fact that a small percentage of the people and firms attacked will be compromised, but that can be turned into a steady income stream. It is a numbers game. The classic attacks in this category are ransomware and denial of service attacks for extortion purposes.

Ransomware has become the scourge of modern business. The attack methods themselves are basic but effective. Bulk phishing emails lead to a user clicking on a malicious attachment, their system becomes infected and the ransomware encrypts their storage preventing access to key files, the ransomware extorts a payment (often in bitcoins) from the victim.

The numbers are interesting. The University of Kent ([UKen16]) suggests that 4% of the internet users surveyed had been hit by ransomware. More interestingly 26% of people paid the ransom, and most (some 65%) got their files back as a result – perhaps honour amongst thieves. The average ransom itself is small – often a single bitcoin – typically around $670 according to Symantec ([Syma16]). For those of you who like playing with statistics, try this UK example:

UK population – 65 million ([ONS16])

4% have been hit by ransomware – 2.6 million

26% of people paid up – 0.68 million

$650 average ransom – circa $440 million income

Not too bad… of course the figures are wrong, but they are in the right ballpark. They also omit the impact on businesses. Trend Micro ([Tren16]) provides a view on ransomware attacking UK businesses which helps build up the picture. 44% of firms surveyed were attacked by ransomware in the last 24 months, with a surprising 65% paying the ransom.

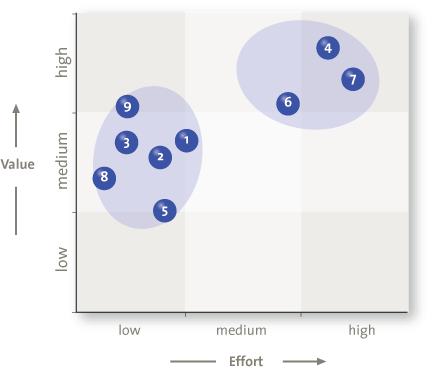

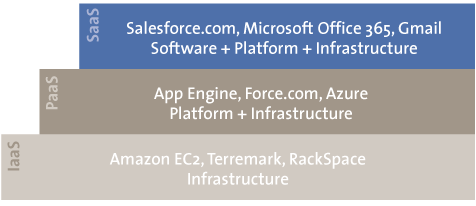

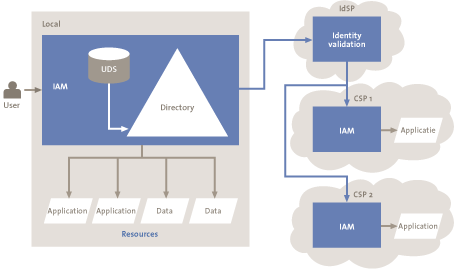

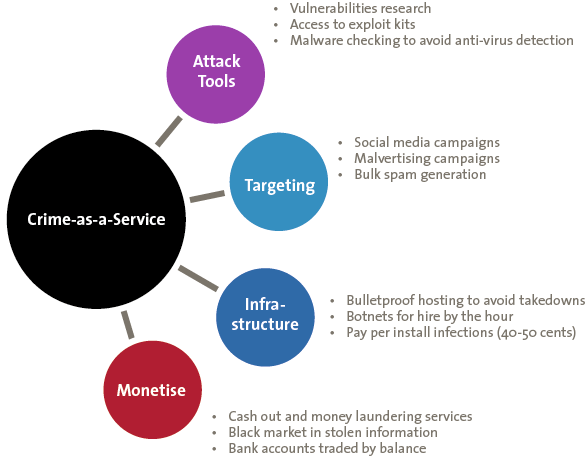

Ransomware has been with us for many years, but there has been a major growth in the range of variety of ransomware since Autumn 2015 ([CERT16]). This reflects a change in the nature of organised crime, with a shift from individual organised crime groups developing their own bespoke ransomware tools to the purchase of ransomware in the form of Crime-as-a-Service (CAAS).

Figure 1. Crime-as-a-Service.

Denial of Service

Ransomware is a key mechanism for extortion, but not the only mechanism. Distributed denial of service attacks which overload web sites and internet facing business portals with malicious traffic are now commonplace. Historically, attacks have been carried out by networks of compromised computers (botnets) which generate large amounts of internet traffic which swamp and overload target websites.

Law enforcement has been increasingly effective in disrupting the operation of botnets working closely with security firms to understand how they operate, the weaknesses in their infrastructure, and how they might be shut down. In particular the Europol Cybercrime Centre (EC3) has played a vital role in co-ordinating action to disrupt such botnets. The takedown of the RAMNIT botnet in February 2015 ([Euro15]) involved Europol working with investigators in Germany, Italy, Netherlands and the United Kingdom – as well as industry partners from Microsoft, Symantec and AnubisNetworks – to disrupt a botnet of over 3.2 million computers.

For their part, the criminals have moved to improve the security of their botnets using encryption to protect their communications, as well as looking for unconventional systems which can be built into new botnets. A recent example reportedly ([OVH16]) used over 145,000 compromised cameras and digital video recorders to create the world’s largest DDOS attack – 1 Tbps. Of course, criminals have also been an early adopter of cloud computing to provide the computing power for their attacks.

Denial of service can now be purchased as Crime-as-a-Service, with it typically costing between $5-$10 per hour to launch an attack against a website. This has resulted in a major increase in short duration relatively unsophisticated DDOS attacks against a wide variety of targets, often linked to attempts to extort small sums (a few bitcoins – some $600) from the victim in return for ceasing the attack.

Tailored Attacks – Online Confidence Tricks

Commodity attacks represent just one element of the threat to organisations and businesses, representing the inevitable background noise of the internet. There are of course examples of organised crime groups investing more time and effort to target firms, their employees and executives.

Business Email Compromises

The single biggest pattern of fraud at the moment is the business email compromise (BEC) fraud or its close relative the CEO fraud. The FBI ([FBI16]) reports over $3.1 billion of such frauds, but most worryingly since January 2015 they have seen a 1,300% increase in levels of reporting as criminals scale up their operations.

The average amount stolen in these frauds is some $140,000. Two recent multi-million pound cases include Action Fraud ([Acti16]) reporting a global healthcare provider who transferred $23 million to an Asia-Pacific bank account, and Reuters ([Reut16a]) reporting a Romanian wire and cable manufacturer who transferred $44 million to a Czech bank account.

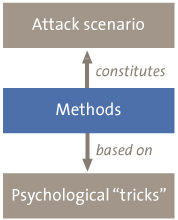

These attacks blend technical attacks with social engineering to carry off what is effectively a sophisticated on-line confidence trick. The target of these frauds are normally financial controllers, corporate treasuries, payment clerks and accounting departments. The aim is simply to trick them into authorising a large financial payment to a bank account of the fraudsters choosing.

The attacks start with careful research into the firm, often undertaken through social media, to identify who are the key individuals who could authorise payments and just what story would work best. This is then followed by meticulously crafted phishing emails which look extremely realistic, using the correct corporate logos, the right email address formats, the typical language used within the company or sector, and even a previous trail of fake correspondence from senior executives providing the context to the request. These phishing emails are often linked to telephone calls and SMS text messages, building the story up over time, establishing confidence, and then cashing out.

Attackers will set up fake email accounts using email ids based on the names of senior executives, or even hack the mail system of lawyers and accountants to send emails to their target.

Box 1. BEC Fraud Tactics.

Business Email Compromise Fraud Tactics

Supplier Change of Banking Details

A fraudulent request is made to change the banking details of a long standing supplier. The email will be well crafted using the correct logos, it may also come from an email account which closely resembles the supplier’s legitimate email address.

Wire Transfer

An email is sent purporting to come from a C level executive. The email may come from a fake email account with an address which looks credible, or may even come from their own personal email account if it can be hacked. The email asks for an urgent wire transfer of funds to an overseas bank for a sensitive and confidential project.

Fake Invoice

An employee has their personal e-mail account hacked, ideally an account they also use for work purposes. Fake invoices are then sent from their email account to suppliers given the account details of the fraudsters account.

Lawyer Impersonation

The fraudster purports to be a lawyer or representative of a legal firm handling confidential and/or time sensitive business on behalf of the firm. The victim is pressurised into transferring funds urgently.

The frauds are backed up by large scale social engineering using sophisticated call centre networks. As an example, in December 2015 Interpol ([Inte15]) co-ordinated the arrest of over 500 such call centre workers across 15 call centres. These arrests included: 245 Chinese and Taiwanese nationals in Indonesia; 168 Chinese nationals in Cambodia; and further arrests in China, Hong Kong, Korea, Thailand and Vietnam which included Korean, Nigerian, Filipino and Russian nationals. Cyber crime has become truly international in scale and reach.

Banking Trojans

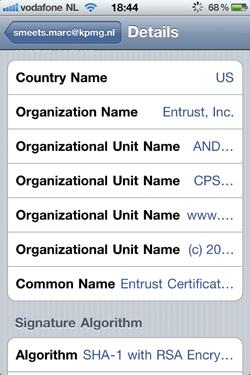

While BEC frauds grow, other traditional forms of cyber crime may be becoming less so, forcing cyber criminals to evolve and adapt. Banking Trojans have been with us for over a decade. Criminals use phishing emails (or compromised web sites) as the means of tricking the user into downloading malware onto their computer. Once installed, the malware will modify the user’s web browser to interpose itself between the user and their e-banking session. This allows the attacker to modify banking transactions, submit their own payment requests, and ensure that the user does not spot those fraudulent transactions when viewing their balances or statements.

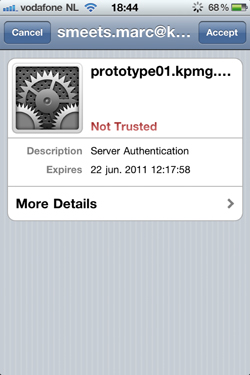

Banks responded to these attacks in a variety of ways, including encouraging customers to use security software, raising awareness, and of course introducing additional authentication checks such as two factor authentication (for example, an SMS message sent to your mobile with a secret code to authorise the transaction). Together with targeted law enforcement action against the developers and operators of these bank Trojans, this has resulted in a major drop in fraud levels to just over 1 bps (0.01%) of transaction volumes.

Organised crime groups are attempting to innovate to overcome these security measures. For example, there has been a major increase in SIM Swap frauds where the criminal attempts to trick mobile network operators into transferring a mobile phone number to a new device (owned by the criminal) by persuading them that the original phone has been stolen. Countering these attacks demands closer collaboration between financial firms and mobile network operators, as well ensuring that the risk scoring undertaken by banks when approving on-line transactions takes into account the device being used.

Card Not Present

Cyber criminals are always interested in payment card details and a vibrant black market exists to sell on such information. The traditional approach of skimming card details at the point of sale or when used in ATM machines continues, with such card details being used to create fake cards for use in countries where the adoption of chip and pin (EMV) card security is less advanced. Over time the opportunities to use such cards will decline, particularly following the decision by US card scheme operators to shift liability to merchants if they do not implement such technology.

So the patterns of attacks change once more, with organised crime groups focussing on Card Not Present frauds where the e-retailer is able to initiate transactions without the cardholder being physically present. According to Financial Fraud Action ([FFA16]) these frauds represented some 70% of payment card frauds in the UK in 2015. E-retailers are increasingly in the sights of organised crime as the digital economy grows.

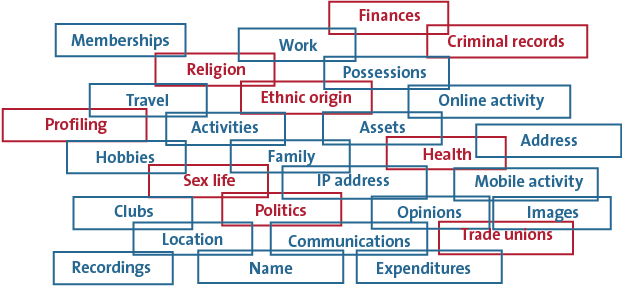

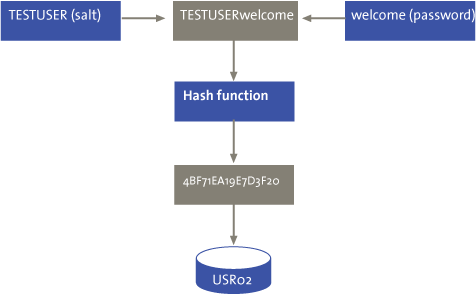

Data Theft

The final category of tailored attacks focuses on data theft. For the most part the target is personal information which can be used to undertake identity theft and fraud. Once again there is a vibrant market in personal information on the dark web, with Fullz (a complete profile for a person including addresses, work details, date of birth, social security numbers, credit card information etc.) selling for up to $15-$65 per person according to Dell Secure Works ([Dell16]).

Bulk data breaches are now endemic, with Breach Level Index ([BLI16]) reporting over 4.8 billion records compromised since 2013. These numbers are likely to be swelled by a recent Yahoo report ([Yaho16]) of over 500 million sets of Yahoo account details being breached allegedly by a state sponsored attacker. Encrypted passwords can be cracked and plaintext recovered (particularly when compromised security questions provide helpful hints). People re-use passwords across multiple systems providing an in for attackers.

High End Attacks – Advanced and Persistent

The most worrying of the attacks, sharing many of the characteristics of a cyber espionage operation and taking place over weeks and months. The attackers start with tailored phishing emails or the use of compromised web sites to distribute malware to their target. Once they have succeeded in infecting an initial system their approach becomes very different. They aim to establish remote control of the infected computer and use that computer as a launch pad to infect other target systems, while keeping a close eye on what the users are doing on those computers. Their monitoring activities may even include capturing copies of the user’s screen and every mouse movement or key stroke on that system. They spend time understanding how the system works, how the fraud controls in the organisation work (including just who needs to authorise payments), and how they might defeat those controls. Then they cash out.

Unlimited Cash Out

There have been a number of examples of banks or payment processors being compromised in order to steal credit card information and then remove the withdrawal limits on those cards prior to them being used overseas. A recent example in International Business Times ([IBT16]) from May this year involved stolen South African bank data being used to create cloned cards which were used to withdraw over 1.5 billion Yen from 14,000 convenience store cash machines across Japan within a 3 hour period. According to the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council ([FFIE14]) a similar operation in 2014 netted the attackers $40 million using just 12 debit card accounts.

Bank System Compromise

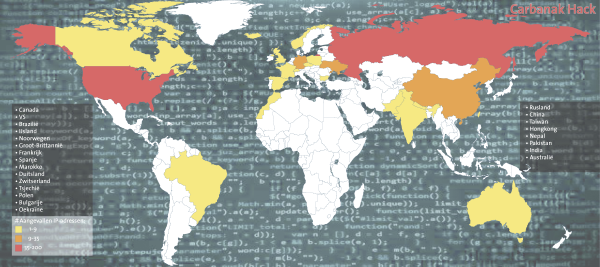

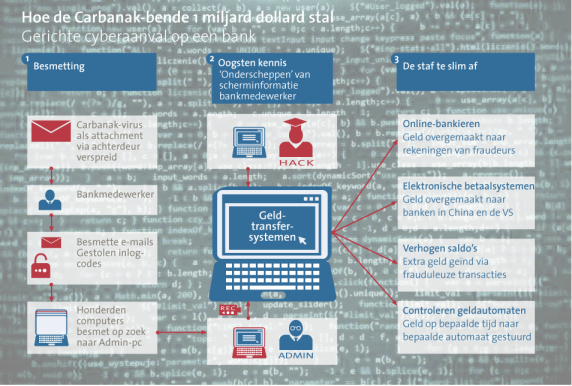

In late 2013 and 2014 an unusual series of attacks occurred against Russian banks. Kaspersky ([Kasp15]) reports that over 50 banks were targeted in a sophisticated operation which came to be known as Carbanak. The attackers used phishing emails which appeared to be from the Russian central bank to gain initial access to the target banks, they then spent two to three months in the systems of each bank looking for an opportunity to cash out. Their cash out strategies were creative ranging from simple inter-bank transfers; to the use of electronic payment channels such as web money, Yandex and QIWI; and even one case of manipulation of bank ATMs to change the denomination of notes in the ATM cash dispenser.

This year we have seen a high profile attack against the Bank of Bangladesh which reportedly ([Reut16b]) attempted $951 million of fraudulent transfers via their SWIFT payment system gateway to various overseas bank accounts, with some $81 million being successfully transferred to bank accounts in the Philippines prior to money laundering through Filipino casinos. Further attacks have also reportedly ([Reut16c]) been attempted against other banks including the theft of some $10 million from a Ukrainian bank.

These attacks raise concerns about the inter-connectedness of the global financial system. The security of that system is dependent on the security of the component banks, with the associated risk that a single weak link will compromise the integrity of the system. SWIFT are now acting to strengthen payment security standards across banks globally, with the Bank of International Settlements expected to follow suit.

Secondary Market Manipulation

A final form of organised crime is one where the victim is less clear. Criminal groups have begun to focus on market sensitive information as a way of making money. In one high profile attack, three major newswire services were reportedly ([USAO15]) broken into, with criminals stealing over 150,000 corporate news releases in the 24 hour window before the newswire released the news to the market. The news releases were then farmed out to a network of traders who could selectively front run the stocks in the market to profit from the price changes which followed the news being made public. The group was alleged to have made over $100 million in profits.

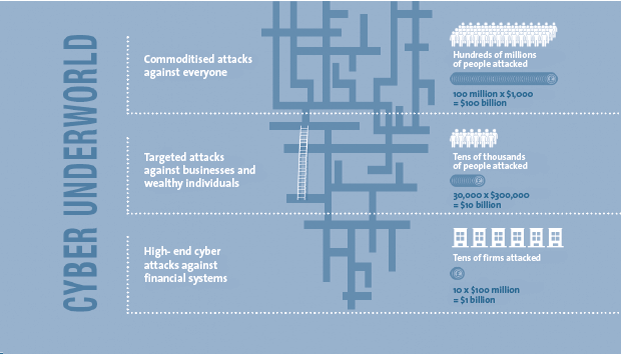

Organised crime is becoming increasingly creative in its approach to money making – and has built a sophisticated cyber underworld.

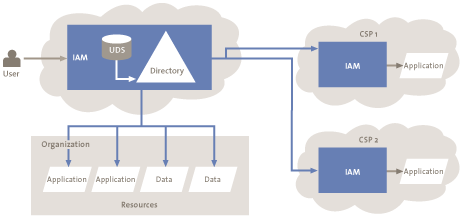

Figure 2. Cyber Underworld. [Click on the image for a larger image]

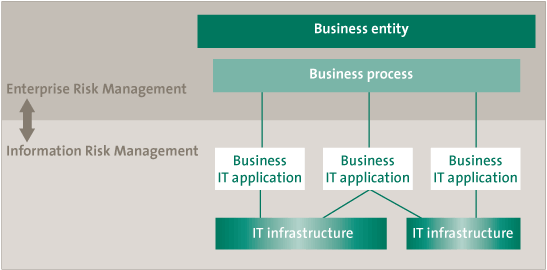

What Does This Mean for Cyber Security?

Get the Basics Right

The basics of security matter – not just for organisations but also for their key suppliers. Commodity attacks impact every firm, if not now, then tomorrow. Firewalls, anti-virus protection, email security and backup policies matter. For firms with an on-line presence, denial of service protection has now become one of those basics. Without these basics organisations are vulnerable to straightforward ransomware attacks, as well as being exposed to the most incompetent of organised crime groups leveraging Crime-as-a-Service offerings.

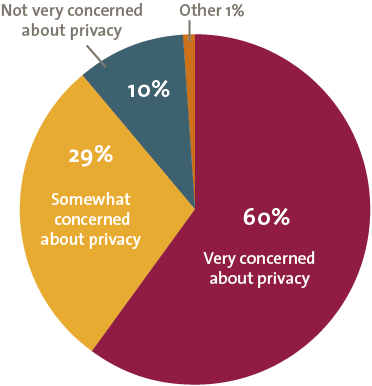

Increasingly firms will be expected to demonstrate that these basics are in place, whether by corporate customers demanding assurances of security from their suppliers, by insurers who refuse to pay out on cyber insurance policies unless reasonable care is being taken, or by regulators who are likely to impose growing sanctions for firms who are perceived to have been negligent in their security or data protection.

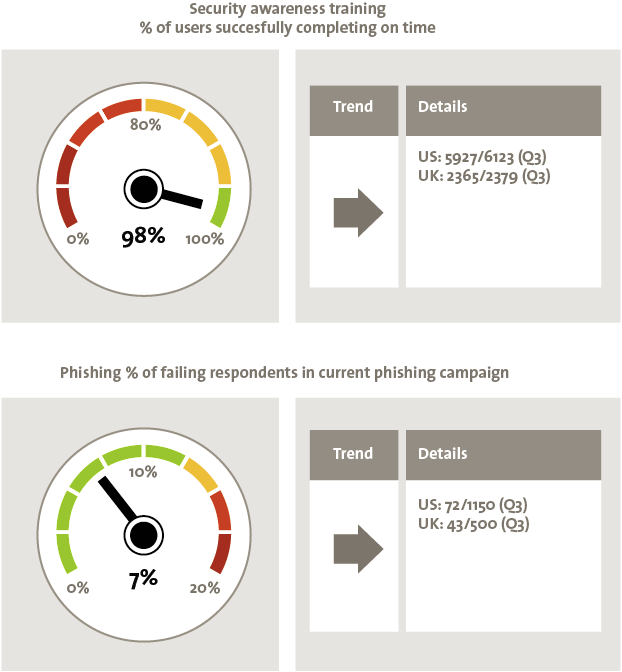

The single most important cyber security basic is not a technical countermeasure, it is education and awareness. Employees are often the weakest link in security, sometimes through carelessness, occasionally deliberate action, frequently through ignorance. Awareness is not just about annual security training, it is about making sure employees are aware of current threats and patterns of criminality, as well as being clear on how to respond if they are targeted by malware or suspicious activity. But the reality remains – people will always be the weakest link in security, and we as security professionals do not do enough to make security straightforward and unobtrusive.

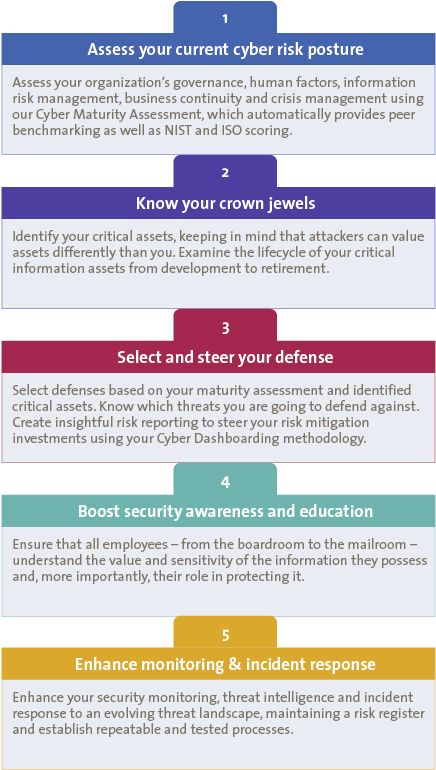

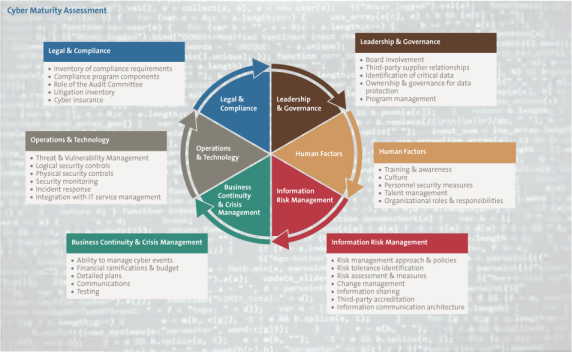

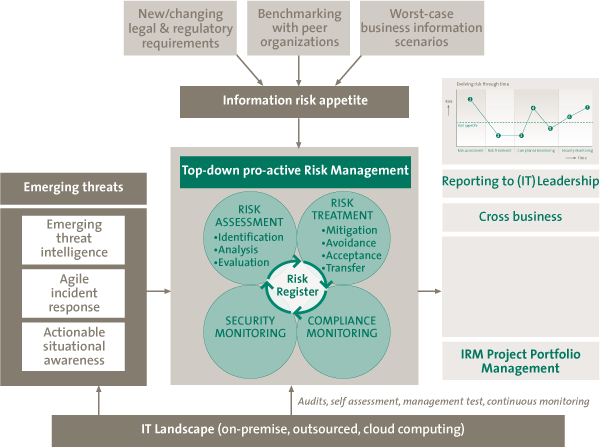

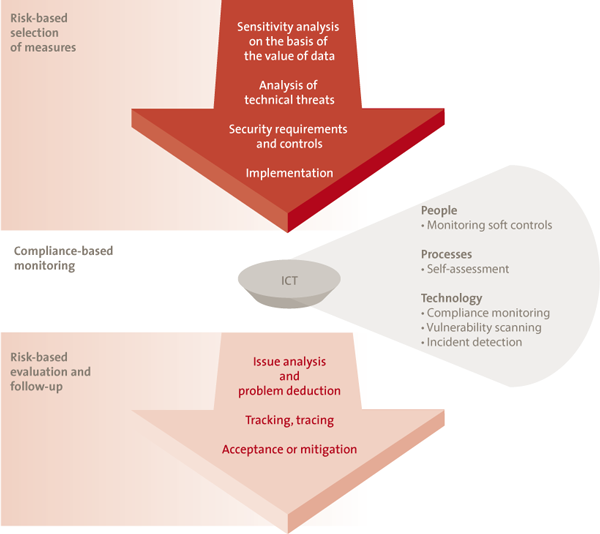

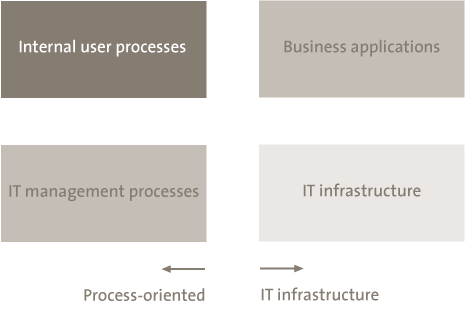

Building on the Basics

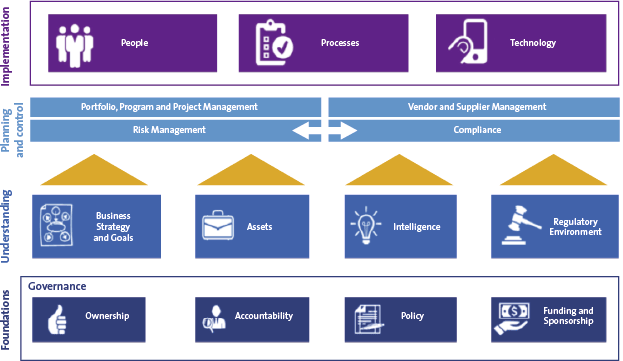

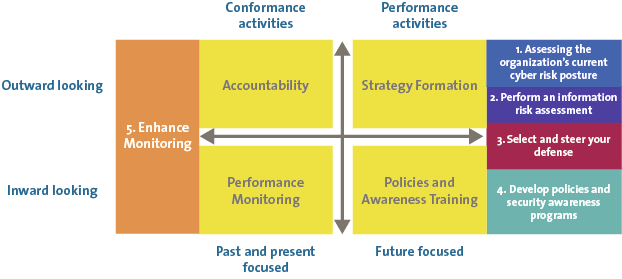

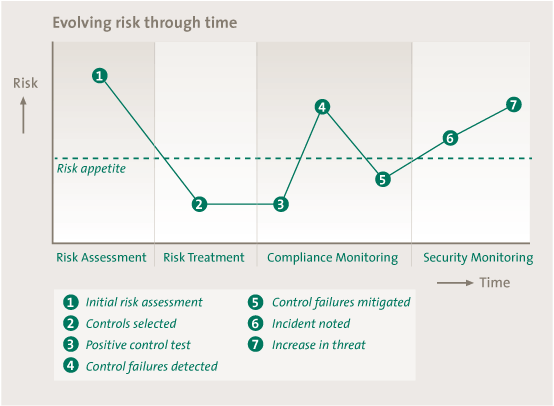

Going beyond the basics, means establishing a robust information security management system which embeds security into corporate systems. At the heart of this is effective leadership and governance – setting out clear ownership, accountability and sponsorship for cyber security at board level, with a well articulated and communicated policy framework.

Cyber security is not a technical issue, it is a business issue which has become increasingly important in our digital world. Success comes when cyber security is embedded into business strategy, and the organisation focuses on the defence of its key assets against a variety of threats including, of course, cyber crime. An organisation’s cyber security stance must also be informed by credible intelligence about a rapidly changing threat, as well as keeping track of the increasingly interventionist regulatory approach adopted by governments worldwide that are frustrated at ongoing cyber incidents.

Cyber security must be embedded into the business processes of the organisation, including: risk management, project management and compliance monitoring. Most critical of all, cyber security should be considered in vendor and supplier management recognising that third parties can create a route for attacks on organisations.

Any cyber security programme must also take a holistic approach which considers not just security technologies, but most critically the people dimension of leadership, education and awareness, along with the process changes to embed cyber security in the organisation. But is this enough, or even sometimes too much?

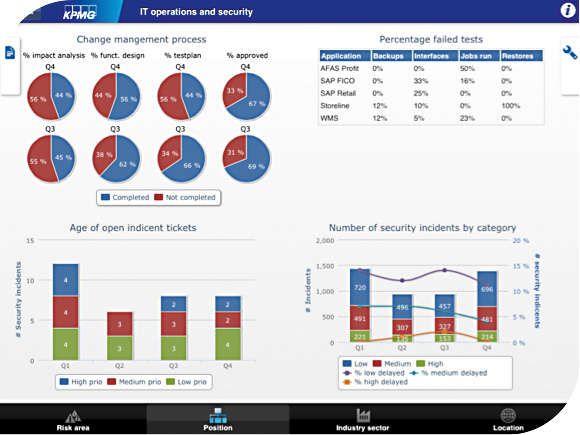

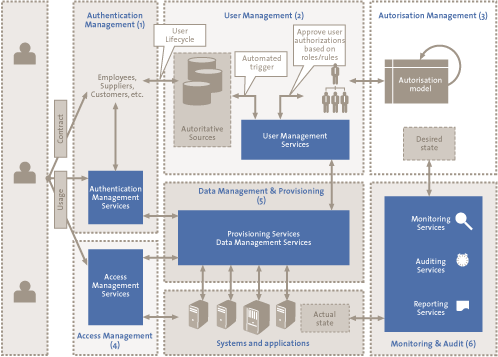

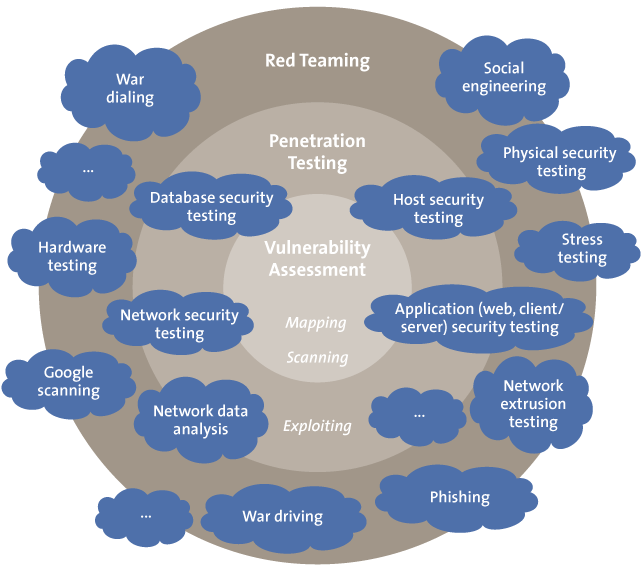

Figure 3. Building out an information security capability. [Click on the image for a larger image]

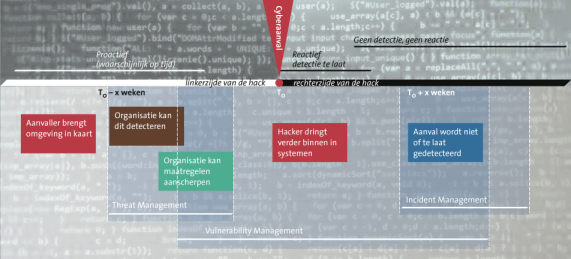

Agility

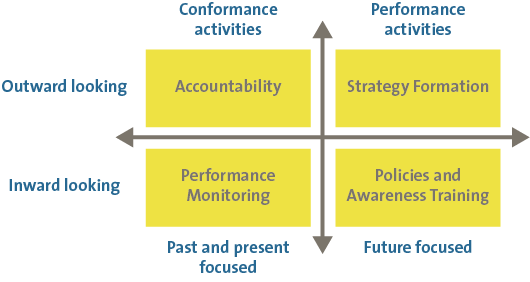

Conventional security wisdom suggests firms should establish a risk based approach to security which reflects the threats which face the firm and the value of the assets they are trying to protect. This approach is valid, but if taken to extremes can translate into a highly structured approach to security which builds governance structures, strategies, policies, reporting and compliance regimes. While important, these structures can become bureaucracies and prove inflexible.

Organised cyber crime is innovative, creative and flexible. The threat evolves with criminal groups changing tactics, tools and targets. This places a premium on our ability to adapt to that threat, including:

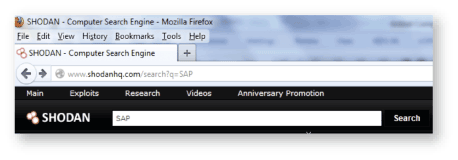

- Threat and Vulnerability Management – keeping track of vulnerabilities across your IT estate, prioritizing which vulnerabilities need to addressed and being able to rapidly deploy security upgrades to counter current threats.

- Security Operations – monitoring unusual and anomalous behaviour or security events within your organisation, setting those events in the context of the business operations, and being ready to respond quickly and effectively to malicious activity.

- Cyber Intelligence – having access to current intelligence on the pattern of cyber attacks against your sector, or even better tailored intelligence matched to your business footprint.

- Red Teaming – a regular programme of testing your security defences from the perspective of an attacker – not just technical testing but intelligence collection and social engineering of your company.

The “Cyber operations” teams undertaking these roles within an organisation need to be given the licence to rapidly respond to new and emerging threats, and with appropriate supervision they need to be allowed to work across the whole organisation with freedom to be innovative in the approaches they take.

Cyber Resilience

Cyber operations are important, but are not the ultimate answer to cyber attacks. This lies in developing a cyber resilient organisation. This phrase, much loved by US and UK regulators, hints at a way of thinking about how an organisation would adapt, respond and recover from a cyber attack. It includes:

- Cyber Scenarios and Exercises – developing credible cyber security scenarios and exercising them at senior level to develop the “muscle memory” needed to respond in an emergency and to test that response.

- Embedding cyber thinking into disaster recovery – making sure that business continuity and disaster recovery plans include the potential for cyber attack not just physical threats to the organisation – this can be a very different way of thinking about points of failure.

- Resilient by design – building resilience into the design of corporate information systems and business processes – including how fall-back and recovery arrangements would work whether manual or automated.

- Cyber insurance – understanding the role of cyber insurance in positioning the business to deal with more extreme cyber scenarios, including access to specialist support in the event of a major incident.

Community Response

No organisation is an island. Organised crime attacks large areas of our economy. Each organisation will see a small part of the activities of the criminals. All of this underlines the need for firms to work together to counter the cyber threat. Historically this has happened in sectors which were most commonly attacked, notably the financial sector (through organisations such as the Financial Services – Information Sharing and Analysis Centre, FS-ISAC) and defence sectors (through various government sponsored schemes). A great example of cross-sector sharing and collaboration is the International Information Integrity Institute (I-4), which brings together large global organisations across a number of sectors: Banking, Telecoms, Insurance, Oil & Gas, Pharmaceuticals, Manufacturing and Tech, for exactly that purpose. It recognises that no one organisation nor one sector can operate in isolation as attacks will often be connected, starting in another sector before traversing to another. Working with other sectors brings new perspectives and an extended peer group for challenge and support.

As the threat develops and grows there is a need to build broader communities linking the financial sector which processes the fraudulent payments to the organisations which unknowingly initiated those payments (for example e-retail). The telecommunications sector also brings unique insights by being able to tie internet addresses to user devices and geographic locations, as well as being a key player in preventing SIM swap frauds.

The pace at which attacks flux and change also demands automation of the exchange of threat intelligence and incident patterns across the community.

Active Cyber Defence

The last component is active cyber defence. The UK government recently announced ([Reut16d]) their intention to establish a national defence capability to actively disrupt cyber attacks against UK firms and citizens. This is expected to include collaboration between government and telecommunication operators to block phishing emails, known bad websites and compromised computers; as well as disrupting the communications between the criminals and the malware they have successfully deployed. We can also expect continuing collaboration between law enforcement and technology firms to takedown botnets and other criminal infrastructure.

A layered model of cyber defence is emerging – based on organisational, infrastructure and national defences – working together to take the offensive against a transnational and sophisticated cyber crime threat.

Conclusion

The cyber crime landscape is changing driven by ruthless rational entrepreneurs backed by a highly effective black market economy in Crime-as-a-Service and stolen personal data. This demands that we look beyond conventional security approaches to focus on creating a security response which is agile and flexible, while focusing on the key assets the organisation wishes to protect and their potential exploitation by criminals. A community response is vital, recognizing that we all face aspects of the threat, and all of us have key pieces in the jigsaw of cyber intelligence. But we also see the start of a new relationship between government and industry, and perhaps a very different approach to active cyber defence and the disruption of organised criminality.

References

[Acti16] Action Fraud, Action fraud warning after serious increase in CEO fraud, February 2016.

[BIS13] Bank for International Settlements, Triennial Central Bank Survey, September 2013.

[BLI16] Breach Level Index, Data breach statistics as at 25th September 2016.

[CERT16] CERT-UK, Is ransomware still a threat?, May 2016.

[CSIS14] Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Net Losses: Estimating the global cost of cyber crime, June 2014.

[Dell16] Dell Secure Works, Underground hackers market, Annual Report, April 2016.

[Euro15] Europol, Botnet taken down through international law enforcement co-operation, February 2015.

[eMar16] eMarketer, Worldwide Retail eCommerce Sales, 2016.

[FBI16] Federal Bureau of Investigation, Business email compromises, Public Service Announcement, I-061416-PSA, June 2016.

[FFA16] Financial Fraud Action, Fraud the facts 2016, May 2016.

[FFIE14] Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Cyber attacks on financial institutions’ ATM and card authorization systems, April 2014.

[Gart16] Gartner, Information Security, Worldwide Forecast, 2014-2020, 2Q16 Update.

[IBT16] International Business Times, Fraudsters steal $13 million from over 1,400 ATM, May 2016.

[Inte15] Interpol, More than 500 arrested in INTERPOL operation targeting phone and email scams, December 2015.

[Kasp15] Kaspersky, Carbanak APT, the great bank robbery, February 2015.

[ONS16] Office of National Statistics, Overview of the UK population, February 2016.

[OVH16] OVH, https://twitter.com/olesovhcom/status/778830571677978624, September 2016.

[Reut16a] Reuters, Germany’s Leoni defrauded of 40 million Euros, August 2016.

[Reut16b], Reuters, Bangladesh Bank official’s computer was hacked to carry out $81m heist, May 2016.

[Reut16c], Reuters, Ukraine central bank flagged cyber attack in April, June 2016.

[Reut16d], Reuters, GCHQ looks at creating national internet firewall, September 2016.

[Syma16] Symantec, Special Report: Ransomware and Businesses, 2016.

[Tren16] Trend Micro, UK businesses bullish about ransomware, September 2016.

[UKen16] University of Kent, Cyber Security Survey, September 2016.

[USAO15] US Attorney’s Office, Nine people charged in largest known computer hacking and securities fraud scheme, August 2015.

[Yaho16] Yahoo, An important message about Yahoo user security, https://yahoo.tumblr.com/post/150781911849/an-important-message-about-yahoo-user-security, September 2016.