Het hart van de IT binnen de financiële dienstverlening is in veel gevallen vele jaren oud, bestaat uit veel maatwerk en dateert van ruim voor het internettijdperk. Nieuwe toetreders konden opnieuw beginnen. Hierdoor hebben ze minder last van complexe organisaties en kunnen ze vanaf de start gebruikmaken van technologie die wel voor het internettijdperk is ontworpen. De klanten van financiële dienstverleners zijn nog erg honkvast. Door de grote aantallen klanten zijn de bestaande organisaties ook nog steeds winstgevend. Maar hoe lang duurt het nog voordat klanten de digitale proposities van de nieuwe toetreders massaal omarmen en een retailachtige ‘disruption’ veroorzaken? De software is gewoon op de markt beschikbaar. Dit artikel gaat in op de mogelijkheden die de implementatie van een standaardsoftwarepakket biedt voor het standaardiseren en harmoniseren van de business.

Inleiding

Honderden banen weg bij ABN AMRO, ING schrapt extra banen, vierduizend banen weg bij Achmea. Deze banen vervallen niet door tegenvallende inkomsten (ING heeft zelfs de staatssteun versneld afbetaald). Vooral de ongekende digitaliseringsslag die de branche momenteel doormaakt heeft impact. Wie ontvangt er tegenwoordig nog bankafschriften of gaat naar een verzekeringsadviseur voor een autoverzekering?

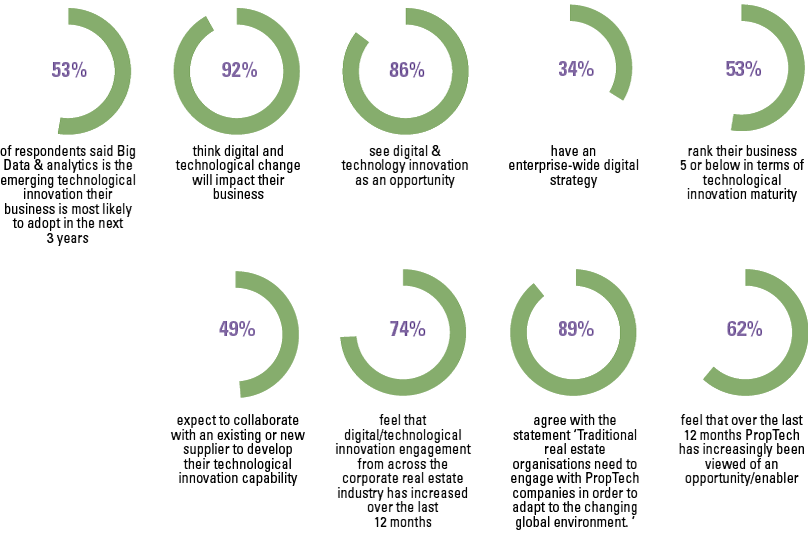

Dit is echter nog maar het begin. Zoals ook door [Koot15] onderkend, ondergaan we een digitale informatierevolutie waarin geïntegreerde waardeketens op dagbasis kunnen worden gedefinieerd. Klanten verwachten steeds meer functionaliteit online en realtime. Dit vereist informatiegedreven, flexibele organisaties die zich snel kunnen aanpassen aan een veranderende omgeving. IT is in deze organisaties een commodity geworden.

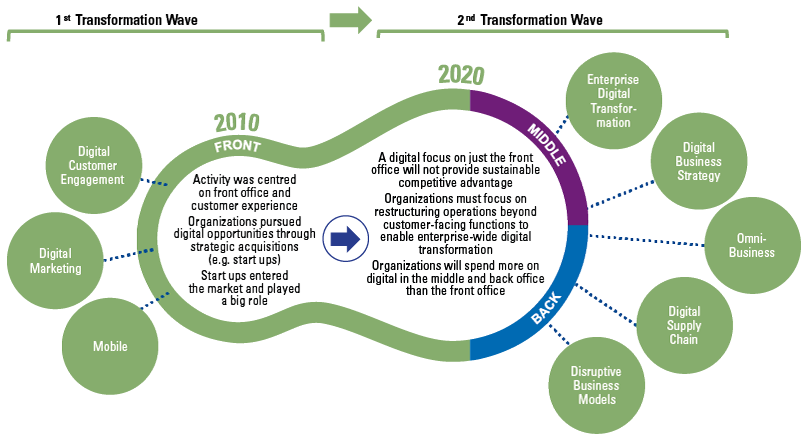

Het hart van de IT binnen de financiële dienstverlening is in veel gevallen vele jaren oud, bestaat uit veel maatwerk en dateert van ruim voor het internettijdperk. Er was toen nog geen 24/7 dienstverlening of selfservice. In de financiële dienstverlening is de digitalisering van de laatste jaren vooral gericht geweest op het digitaliseren van de front end rondom het klantcontact. Aan de achterkant zijn er nog veel op papier gebaseerde processen die worden uitgevoerd in een organisch gegroeide complexe organisatie. In informatiegedreven en flexibele organisaties zijn ook deze processen vergaand gedigitaliseerd.

Nieuwe toetreders, zoals diverse spaarbanken en online verzekeraars, konden opnieuw beginnen. Hierdoor hebben ze minder last van bovengenoemde complexe organisaties en kunnen ze vanaf de start gebruikmaken van moderne technologie. Technologie die wél is ontworpen voor een digitale samenleving, vaak in samenwerking met jonge (Nederlandse) IT-leveranciers. Dit betreft grotendeels standaardsoftwarepakketten die draaien op algemeen beschikbare infrastructuur voor een stabiele administratie en een flexibele voorkant. Deze (combinatie van) pakketten (stelt) stellen nieuwe toetreders in staat om klanten voor veel lagere kosten een veel meer digitale propositie aan te bieden. Bijvoorbeeld het volledig online klant worden, (near) realtime producten afsluiten of wijzigen, location-based services en diensten als gevolg van een betere ontsluiting van gegevens (zoals tools om klanten financieel zelfredzaam te maken).

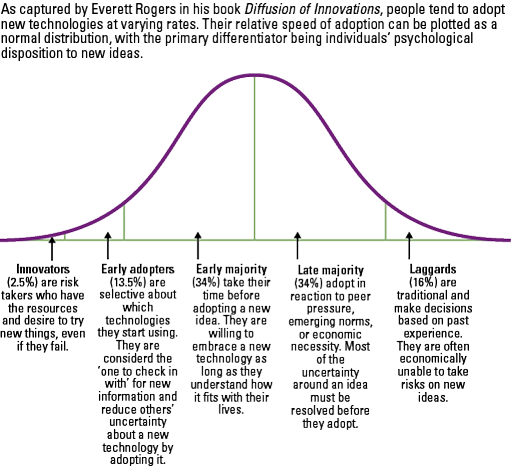

De klanten van financiële dienstverleners zijn nog erg honkvast. Door de grote aantallen klanten zijn de bestaande organisaties ook nog steeds winstgevend. Maar hoe lang duurt het nog voordat klanten de digitale proposities van de nieuwe toetreders massaal omarmen en een retailachtige ‘disruption’ veroorzaken?

De nieuwe toetreders kunnen een stormloop hoogstwaarschijnlijk probleemloos aan; het is immers een kwestie van ‘een server erbij’ om de capaciteit te verhogen.

De standaardsoftwarepakketten die de nieuwe toetreders gebruiken zijn gewoon op de markt beschikbaar. Maar hoe is een dergelijk standaardsoftwarepakket passend te maken in een tientallen jaren oude en complexe organisatie met duizenden of zelfs miljoenen lopende contracten? Of is het andersom? Digitalisering is veel meer dan alleen een nieuw systeem implementeren. [Koot15] gaf al aan dat de huidige demand-supplymodellen op spanning staan met de verandering naar steeds meer IT-commodity, waarbij de manier van transactieverwerking niet langer onderscheidend is voor de dienstverlening en gebruikers met behulp van Big Data, cloud, web- en mobiele technologie steeds meer zelf vorm kunnen geven. Er is een radicaal andere werkwijze nodig ([Koot15]).

Verandering in IT vereist complexiteitsreductie van de business

In hun artikel over One Company en One IT stellen Koot en Pasman [Koot14] dat “het reduceren van de IT-complexiteit (…) een belangrijk onderdeel” is bij het invoeren van eenvoud en consistentie. Daarnaast stellen zij dat het niet de oplossing is om complexiteit te reduceren tot een IT-vraagstuk, omdat “de complexiteit in IT slechts een symptoom is van de problemen op een veel dieper niveau in de organisatie”. “Standaardisatie van gegevens, de werkwijzen en processen” is een randvoorwaarde voor “een omgeving (…) waarin de stroomlijning van IT succesvol kan zijn.” “Het gezamenlijk bepalen van de functionaliteit leidt nogal eens tot het vaststellen van de ‘grootste gemene deler’. (…) Daadwerkelijke harmonisatie vraagt om (harde) keuzes en versimpeling. Niet om gepolder.” IT kan echter wel als breekijzer dienen om bestaande patronen en denkwijzen binnen de organisatie te doorbreken. Dit geldt voornamelijk voor het standaardiseren van mid- en backoffice(transactie)processen met grote volumes die de kern van een onderneming vormen.

Een standaardsoftwarepakket als breekijzer

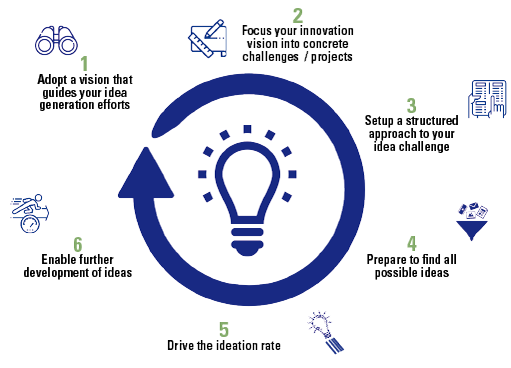

Een standaardsoftwarepakket biedt functionaliteit ‘out-of-the-box’. De kans is echter groot dat de volledige functionaliteit van een pakket niet een op een aansluit bij de bestaande functionaliteit in een legacysysteem dat vervangen moet worden. Om het softwarepakket passend te maken én zo veel mogelijk out-of-the-box te houden zijn keuzes nodig. Precies de harde keuzes die Koot en Pasman benoemen komen met een standaardsoftwarepakket boven tafel. Een standaardsoftwarepakket met de juiste aanpak kan hierdoor als breekijzer dienen om de organisatie te standaardiseren en harmonisatie te forceren.

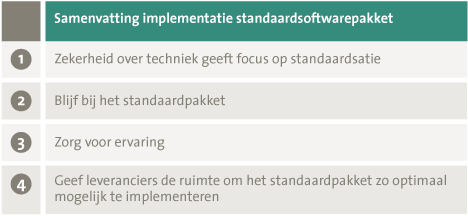

In veel markten zijn dergelijke standaardpakketten beschikbaar, bijvoorbeeld voor ERP, boekhouding of debiteurenbeheer. Ook op het gebied van Core Banking of Core Insurance zijn vele bewezen alternatieven aanwezig. Doordat dergelijke pakketten bij concurrenten al in gebruik zijn, is er de zekerheid dat tijdens de implementatie technische problemen het bereiken van de beoogde standaardisatie niet zullen frustreren. Hoe meer implementaties van de standaardoplossing zijn gedaan, hoe meer zekerheid er bestaat over de bruikbaarheid van het pakket. Dit voorkomt ‘gepolder’ over de huidige werkwijze versus het standaardpakket. Tijdens de implementatie kan de aandacht volledig uitgaan naar de versimpeling en standaardisatie van de organisatie. Maatwerk moet daarbij zo veel mogelijk vermeden worden. Hoe meer maatwerk, hoe meer een pakketimplementatie op klassieke softwareontwikkeling gaat lijken. Bovendien leidt maatwerk in beheer tot hogere onderhoudskosten en wordt de uitrol van nieuwe releases complexer, doordat extra testwerk van het maatwerk noodzakelijk is.

Leveranciers van standaardpakketten hebben ervaring met de implementatie bij andere partijen én hebben baat bij een succesvolle referentie. Deze ervaring en hun kritische blik zijn waardevol bij een zo optimaal mogelijke implementatie van het pakket en de verandering van werkwijzen, ondanks dat geen implementatie hetzelfde zal zijn. Immers, niet de implementatie is het doel, maar juist de harmonisatie, productrationalisatie en digitalisering die mogelijk gemaakt worden.

Casestudy’s

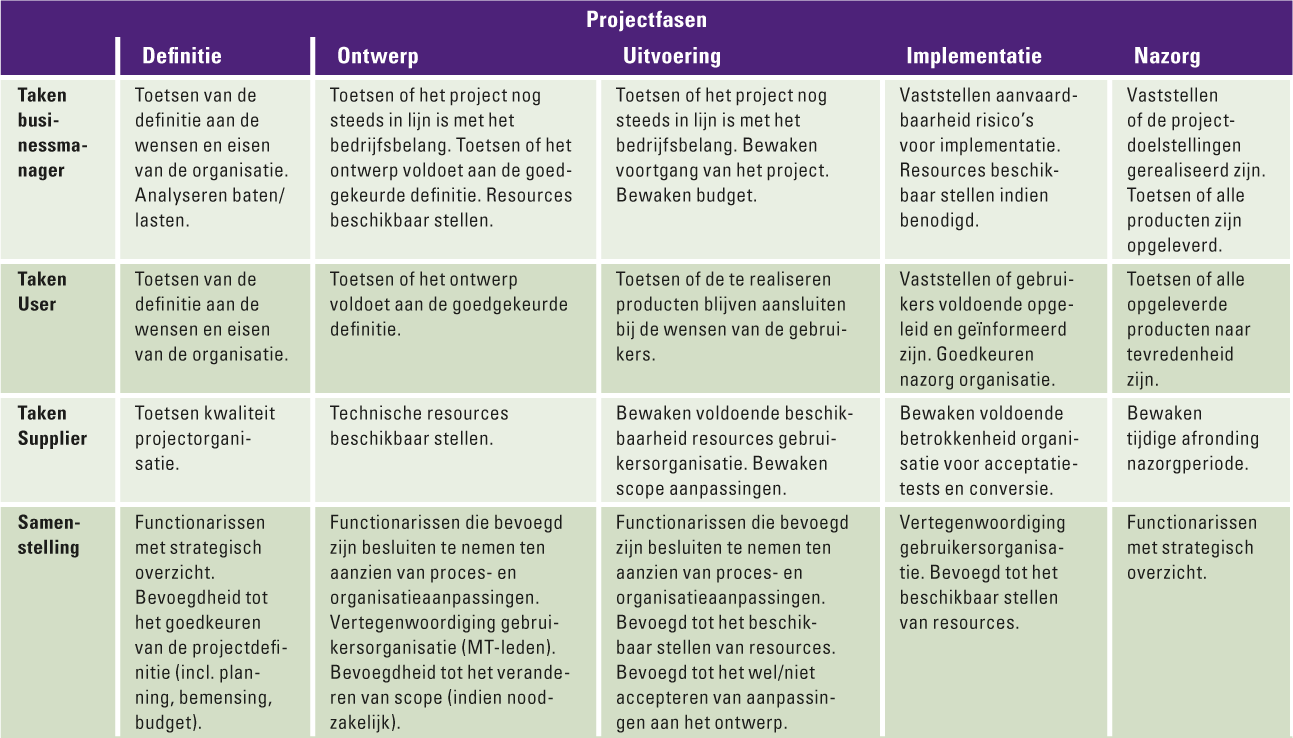

Opgenomen casestudy’s zijn voorbeelden van praktijksituaties waarin KPMG de aanpak om met behulp van een standaardsoftwarepakket de complexiteit te reduceren is tegengekomen. De eerste casestudy betreft een middelgrote verzekeraar met een sterk verouderd administratiesysteem. In de huidige verzekeringsmarkt is het aanbieden van online producten voor een lage prijs een randvoorwaarde. Dit was voor de verzekeraar onmogelijk, vanwege hoge interne kosten als gevolg van enerzijds een kostbaar en verouderd IT-landschap en anderzijds hoge administratieve kosten als gevolg van diversiteit in werk. Meerdere pogingen om het systeem te vervangen waren eerder gestrand als gevolg van de complexiteit in zowel organisatie als IT.

Enkele jaren geleden nam de organisatie het besluit om een bewezen standaardsoftwarepakket in te zetten als hefboom voor het reduceren van organisatorische complexiteit. Veel detail requirements werden aan de kant geschoven en het budget voor maatwerk was minimaal. Bovendien kwam er een duidelijke scheiding tussen ‘oud’ en ‘nieuw’, het pakket werd minimaal gekoppeld aan de bestaande IT en er werd een ‘greenfield’-afdeling ingericht. Eigenlijk werd de verzekeraar vanaf de basis opnieuw opgebouwd. Met behulp van het pakket is in negen maanden gelukt wat eerder in drie jaar niet lukte, namelijk de migratie van een groot deel van de verzekeringsportefeuille.

De sleutel tot succes van dit project zat in de standaardisatie van producten en processen met behulp van het softwarepakket. Dit dwong de organisatie ertoe om te veranderen, hoewel dit niet altijd eenvoudig was. Aan de bestuurstafel zijn meerdere discussies gevoerd over het wel of niet aanpassen van het pakket of het inzetten van een ander systeem, omdat er qua functionaliteit betere alternatieven noodzakelijk of beschikbaar waren. Steeds werd voor de werkwijze van het pakket (als best of suite) gekozen. Het bestuur voelde zich gesteund door de wetenschap dat het softwarepakket bij vergelijkbare verzekeraars naar tevredenheid in gebruik was. De aanpassingen die wél werden doorgevoerd, hadden vaak te maken met de onderscheidende propositie van de verzekeraar. Het belangrijkste doel bleef standaardiseren om digitalisering mogelijk te maken en kosten te verlagen. De verzekeraar koos ervoor om eerst het nieuwe systeem naar productie te brengen, ook al had dit in extreme gevallen tot gevolg dat een stap(je) terug werd gezet.

De tweede casestudy betreft een pakketimplementatie bij een internationale bank, die gewend was om systemen zelf te ontwikkelen. Bij wijze van pilotproject besloot de bank een standaardpakket te implementeren. De argumenten voor deze aanpak waren onder meer de snelheid van productontwikkeling en marktontsluiting. Ook de integratiemogelijkheden van het standaardpakket versus zelfbouw speelden een belangrijke rol.

De ambitie van het programma was beperkt, het was immers een pilotproject. Slechts een gedeelte van de ondersteunde standaardfunctionaliteit van het pakket werd in gebruik genomen. Het systeem moest in een complex landschap geïntegreerd worden met vele interfaces en systeemlogica die buiten het standaardpakket uitgevoerd werd. Toch slaagde het programma erin om aan te tonen dat het standaardpakket kan functioneren in een landschap van maatwerkproducten en leverde het een nieuw ‘long-term liability’-product op dat via de online banking-kanalen aan retailklanten kon worden aangeboden. Als proof of concept was het programma daarom succesvol, maar de werkelijke kracht van de standaardoplossing zou pas ten volle benut kunnen worden als meer functionaliteit van het pakket gebruikt zou worden. Technisch waren de doelstellingen echter blijvend ambitieus, waarbij de noodzaak om aan te tonen dat vervanging van legacymaatwerksystemen door een dergelijk standaardpakket een goede oplossing is.

Vaker werd besloten om de organisatie en werkwijzen aan te passen aan de wijze waarop deze werden ondersteund door het systeem in plaats van andersom. Ook koos de bank er bij voorbaat voor om een goed gedocumenteerd algemeen beschikbaar banking framework voor standaardprocessen te hanteren als blauwdruk voor haar processen. Hierdoor konden discussies over organisatie- en procesverandering eenvoudiger worden kortgesloten.

Harde keuzes

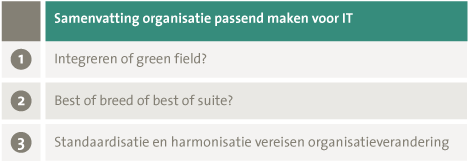

Beide cases zijn voorbeelden van een succesvolle pakketimplementatie. Er vallen echter enkele keuzes op die, los van het standaardpakket, het succes van de standaardisatie mede hebben bepaald. Allereerst de keuze om de nieuwe IT wel of niet te integreren met de legacy-IT-omgeving. Ondanks de huidige vraag naar geïntegreerde klantbeelden en systemen heeft de verzekeraar ervoor gekozen om de nieuwe IT zo veel mogelijk te isoleren. Deze keuze zorgde voor veel weerstand vanuit de business, doordat management- en salesinformatie gedurende het project niet geïntegreerd voorhanden waren. Door een dergelijke lastige keuze te maken werd tijdelijk een stap teruggezet om het eindresultaat dichterbij te brengen, want de keuze voorkwam complexe interfacing en versnelde het project.

Het tweede punt betreft de keuze voor een ‘best of breed’ of ‘best of suite’. Zeker wanneer voor een breed backofficepakket wordt gekozen, zijn er op losse onderdelen (bijvoorbeeld informatievoorziening, CRM, CMS) betere gespecialiseerde alternatieven te vinden. Tijdens de implementatie is het beste gespecialiseerde alternatief verleidelijk vanuit een beperkt inhoudelijk perspectief. Een dergelijk alternatief kan echter tot complexiteitverhoging leiden met mogelijk dubbele functionaliteit tot gevolg. De organisatie dient zich de vraag te stellen of de grotere complexiteit als gevolg van meerdere systemen opweegt tegen de geboden toegevoegde waarde van de extra complexiteit.

Het derde en belangrijkste leerpunt uit de casestudy’s is de impact die standaardisatie op de organisatie heeft. Deze is fors en vereist een sterke verandercapaciteit. Dit wordt niet eens zozeer door de IT veroorzaakt, want standaardsoftwarepakketten zorgen meestal juist voor een versimpeling op dit vlak doordat ze draaien op basis van gangbare standaarden. Juist de organisatie zal moeten veranderen, enerzijds doordat het pakket een andere werkwijze vereist, anderzijds om de noodzakelijke digitaliseringsslag te maken. Deze digitaliseringsslag wordt niet alleen gemaakt door een nieuw pakket in te voeren, maar vereist een compleet nieuwe manier van werken, waarbij klanten meer processen zelf gaan uitvoeren en de organisatie zich richt op data-analyse waarmee echt het verschil kan worden gemaakt. Dit vraagt om herinrichting, opleidingen en zelfs werving van personeel met nieuwe vaardigheden. Om innovatie echt de ruimte te geven is het bovendien te overwegen om, net als de verzekeraar in onze case, niet alleen de IT, maar de gehele organisatie vanaf de grond opnieuw op te bouwen. Een vergelijkbare overweging heeft bij BMW tot de vernieuwende i-serie (hybride aangedreven auto’s) geleid. Bovendien wordt op deze manier de draaiende organisatie niet opgezadeld met de kinderziektes van een nieuw systeem, kan de nieuwe wereld met klein volume worden uitontwikkeld en vormt de nieuwe wereld de basis om de oude wereld naartoe te migreren.

Het is dus andersom. Voor vergaande standaardisatie en harmonisatie met behulp van een standaardsoftwarepakket moet de organisatie passend worden gemaakt voor IT.

Morgen mee beginnen:

- Ga kijken wat de concurrentie doet en sluit producten af bij digitale (kleine) spelers.

- Bepaal welke standaard-IT-systemen deze spelers gebruiken en analyseer deze oplossingen.

- Voer een eerste grove rationalisering uit van bestaande producten en processen.

- Neem maatregelen ter compensatie van bekende valkuilen binnen de organisatie.

- Houd het klein en experimenteer, ‘it will be a bumpy ride anyway’.

Literatuur

[Koot14] William J.D. Koot en Jochem Pasman MSc, ‘One IT’ volgt uit ‘One Company’; en niet andersom, 2014, http://www.it-executive.nl/content/redactioneel/one-it-volgt-uit-one-company-en-niet-andersom.

[Koot15] W.J.D. Koot, E.J. Mutsaers en I.E. Veen RE, Het demand-supplymodel voorbij!?, Compact 2015/1, https://www.compact.nl/artikelen/C-2015-1-Koot.htm.