With COBIT 5 out in the open for over three years now, the time has come to step back and review its accomplishments and acceptation so far. Does ISACA’s latest achievement in the art of COBIT live up to the expectations it created? And does it fulfill its ambitions? How does it differ from its predecessor? Are there now two camps – advocates and opponents – who have retreated into their trenches, harassing one another with arguments? Is the framework slowly but firmly gaining ground? Can we conclude that COBIT 5 is indeed a giant leap forward in the art of IT Governance and IT Management, or can we deduce that COBIT 5 has overplayed its hand and is just a bridge too far?

This is an article with a critical tone, combined with the opinion of three subject-matter experts closely related to COBIT.

This article has been written in a personal capacity.

Introduction

COBIT 5 was released about three years ago. We observed initial enthusiasm at several organizations but this was also followed by hesitance about moving from COBIT 4.1 to COBIT 5. The focus remains basically on IT processes, and much less on the newer ‘features’ such as the principles, enablers and others. Furthermore, despite the fact that several COBIT 5 and related publications are already available and more continue to be published, the existing adoption rate in organizations seems to moving very slowly, at least in the Netherlands and Belgium. With the addition of enthusiastic online discussions on different platforms, between die-hard believers and critical and wandering spirits, this has brought us to explore COBIT 5 further and to offer some comments on the evolution and changes made by ISACA. The purpose of this article is not to provide an in-depth overview or insight of all elements of COBIT 5, nor to provide a guide on how to use COBIT, but to list and explain some observations and thoughts based upon our professional experience.

A brief history of COBIT

Before we dive in the details of COBIT 5 and discuss its implementation, it is good to look back and see where COBIT has come from. The description below is largely based on [Bart15].

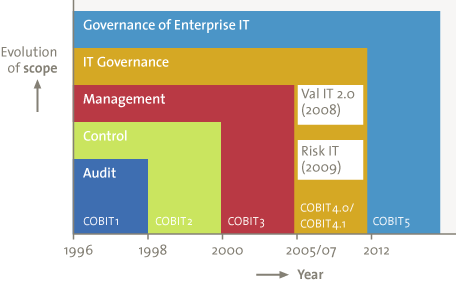

The latest version of COBIT is now presented as the framework for the Enterprise Governance of IT, but this has not always been the case or the focus. COBIT was developed by ISACA (Information Systems Audit and Control Association) in the mid-nineties, in the (financial) audit community, and its name originates from the abbreviation for ‘Control Objectives for Information and related Technologies’. As is currently still the case, the financial and internal auditors noted an increase in the level of automation at the organizations where they performed audits, creating the need for a framework to support the execution of IT audits. In fact, the first versions of the COBIT framework could be seen as the ‘COSO equivalent model for IT Auditors’. And COSO is still one of the main reference models for COBIT when it comes to internal control. Since the release of COBIT 5, this strongly branded acronym within the (IT) audit world has become consistently less relatable to its original meaning, as subsequently IT Management concepts, IT Governance concepts and now Enterprise Governance of IT concepts gradually found their way into the framework.

With the development of COBIT 3, which was released in 2000, an important element was added to the framework: management of IT. Through the addition of management guidelines, including critical success factors and other metrics, COBIT aimed at becoming a broader IT Management framework, rather than restricting itself to a future as merely an IT auditing and control tool. Another new and important extension of the framework in that version was the IT process maturity model. This model helped IT Management to use the COBIT framework as a method to increase professionalism within its own IT department and even to perform some initial benchmarking. COBIT experienced a real boost from the (internal) audit side when the SOx regulation came into force, putting emphasis on internal controls over IT.

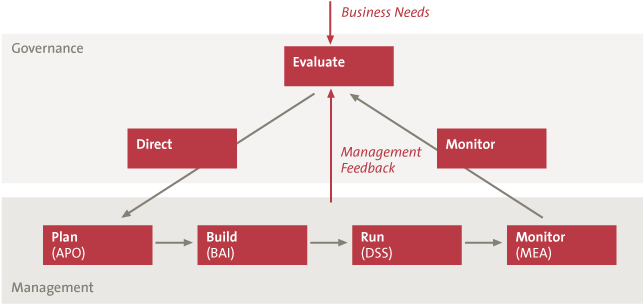

Management, however, is not similar to governance. ISACA defines governance in their COBIT framework as:

Governance ensures that stakeholder needs, conditions and options are evaluated to determine balanced, agreed-on enterprise objectives to be achieved; setting direction through prioritization and decision making; and monitoring performance and compliance against agreed-on direction and objectives ([ISAC12])

The board of directors is responsible for the overall governance, but specific governance responsibilities can be delegated to special organizational structures at another level ([ISAC12]).

Corporate Governance became more and more important throughout the years and ISACA felt the need to further improve the COBIT framework by moving upwards in the organizational hierarchy from IT Management to IT Governance. The release of COBIT 4 in 2005, later followed by COBIT 4.1, supported this. In COBIT 4 a number of new concepts were added, amongst others:

- Roles and Responsibilities per IT Process

- Alignment between Business Goals and IT Goals

- The relationship and dependencies between IT Processes

- Additional COBIT publications such as the Control Practices and the Assurance Guide. Also a number of publications related specifically to IT Governance were released.

In addition to COBIT 4.1, two separate frameworks were introduced: Val IT and Risk IT. It was felt that the management of IT Risk and the management of IT Value were needed in addition to COBIT 4.1 in order to realize the full extent of IT Governance. In essence, the Risk IT framework was nothing new, as it included a large number of basic risk concepts which could be found in other risk methodologies as well, only now they were more adapted to IT. And although there was some very relevant and practical information to be found in the Risk IT framework and publications, this is – as far as we know – perhaps part of the reason why the acceptance and use of the Risk IT framework has been limited, at least in the Netherlands and Belgium. Another reason might well be that risk in itself is often a neglected and/or underestimated factor, and that risk management processes are not always easy to implement. In addition, the processes of Val IT were not part of the basic COBIT framework and therefore Val IT could be seen as a separate – much more business-oriented – model providing additional value and using a more understandable vocabulary and language for the business. However, to our knowledge, the use and implementation of the Val IT processes were also limited, although we have come across a number of usages in Belgium and the Netherlands. It is noteworthy that Val IT concepts are much closer to the business by definition, and could possibly already exist in a similar form but at another place in organizations without the explicit link to IT, and not identified as part of Val IT.

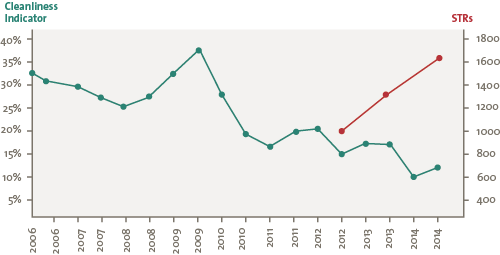

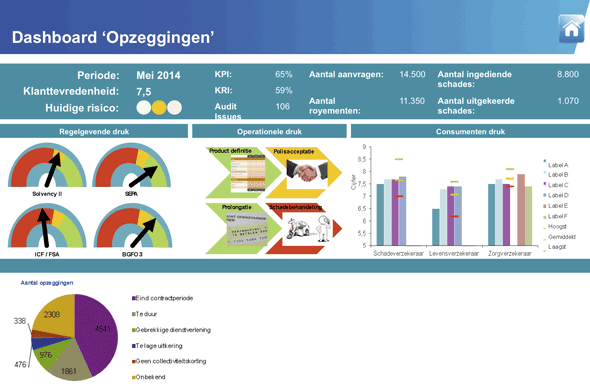

Figure 1. History of COBIT (ISACA).

The advance of COBIT 5 – where did it come from and what are the changes in relation to COBIT 4.1?

After several years of relative silence around COBIT, COBIT 5 saw the light in early 2012, with a publication subtitled ‘A Business Framework for the Governance and Management of Enterprise IT’. This already hints at an important – and, to some, absolutely necessary – scope extension: from IT Management (v3) via IT Governance (v4/4.1) to a business framework for Enterprise IT. ISACA claims that COBIT 5 is a holistic framework for the entire organization, and has therefore also consolidated and integrated Val IT and Risk IT into COBIT 5.

According to De Haes and Van Grembergen, Enterprise Governance of IT is defined as: “an integral part of Corporate Governance and addresses the definition and implementation of processes, structures and relational mechanisms in the organization that enable both business and IT people to execute their responsibilities in support of business/IT alignment and the creation of business value from IT-enabled business investments” ([Haes09]).

Interestingly enough, ISACA has not only changed its communication form by using the only acronym of COBIT nowadays, but the well-known element of ‘Control Objectives’ has also disappeared, at least in name and traditional form. Instead, COBIT 5 uses the term ‘Management Practice’. This is almost a signal to the outside world that a new era has come, and the past has been left behind!

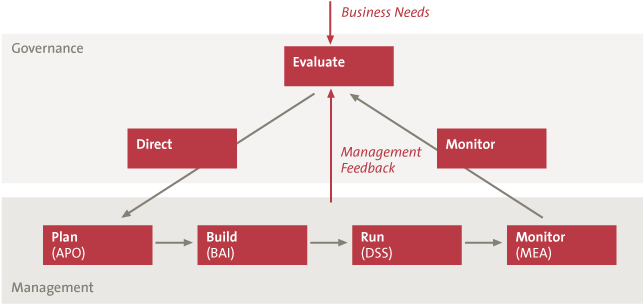

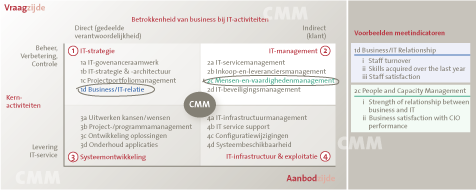

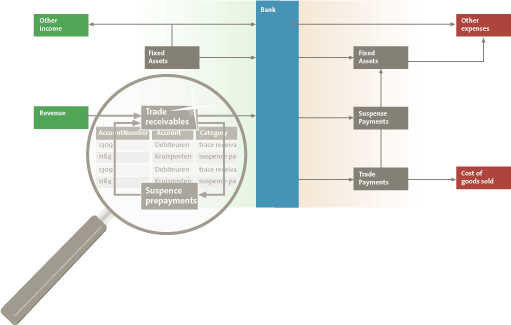

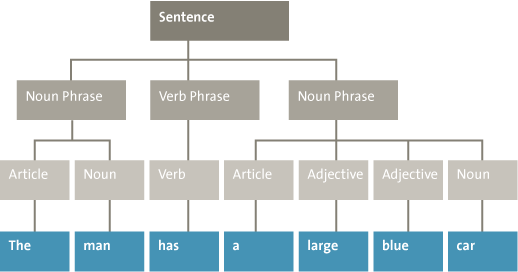

Although in COBIT 5 the processes are described in detail in a separate publication rather than as part of the overall framework as was the case with COBIT 4.1, the content of the IT processes has been kept intact. The combination of Management Practices with related Activities can easily be used to distill the Control Objectives and related controls to satisfy the needs of the IT auditor. The naming no longer matches, but the description in COBIT 5 still helps the use from an operational perspective. COBIT 5 has increased the number of processes from 34 to 37 in total, and has made a distinction between 5 Governance processes and 32 Management processes. The processes have been revised and restructured, while new processes have been introduced as well. The operational processes (APO, BAI and DSS) are linked to the governance processes (EDM), underlining the alignment between governance and management here too (see Figure 2). Furthermore, the framework provides suggested metrics per process in order to be able to measure the performance of a process.

Figure 2. COBIT IT Processes.

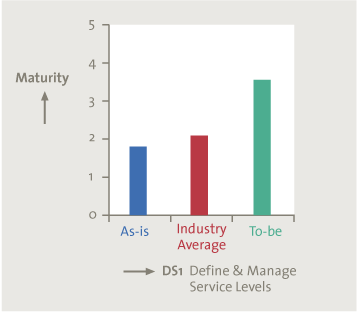

A very important change in the framework can be found in the approach for assessing the IT processes. COBIT 4.1 defined a process maturity model that was initially based on the maturity part of the CMM model of the Software Engineering Institute. This model uses a maturity scale from 0 (non-existent) to 5 (optimized). The maturity framework also provides six generic maturity attributes (such as Awareness and Communication, Skills and Expertise) that should be taken into account when scoring the maturity of any given process. Furthermore, a generic description per maturity level is provided as well as a process-specific description per maturity level. In COBIT 5, ISACA has chosen to move away definitively from the maturity approach in favor of a capability model called PAM (Process Assessment Model) which is based on the ISO 15504 standard that was already available as a separate ‘product’ for COBIT 4.1. PAM also uses a scale from 0 (incomplete) to 5 (optimizing), but the assessment method is much more objective (and complex), as COBIT 5 provides clear descriptions of what needs to be in place per process in order to reach a specific level. The scale might look the same, but the change of assessment method is much more than just a matter of ‘wording’. Organizations will see the bar raised very substantially, even if they only aim to reach a process capability level 1 for any given process, whereas they could have scored a process maturity level 2, for example, in COBIT 4.1. This change has not been well received and many organizations still use the principles of the COBIT 4.1 maturity assessment to determine the maturity level of their COBIT 5 processes, rather than getting involved in much more complex capability assessments. An example we have experienced in the Netherlands, concerns a case where a financial institution requested a maturity assessment based on COBIT 5 (although this is not possible according to the framework) from its IT infrastructure service provider. The only rationale for COBIT 5 was the fact that this was ‘the latest version in the market’. The regulator in this case (De Nederlandsche Bank) does not require any assessment of COBIT 5 as yet. In Belgium we had a similar case for a federal government body, where we used the maturity approach of COBIT 4.1 in support of an IT audit based on COBIT 5.

A minor change to COBIT 4.1 is the phenomenon called ‘information criteria’. In COBIT 4.1 seven information criteria were used to provide guidance to an IT auditor performing an audit: effectiveness, efficiency, integrity, reliability, availability, confidentiality and compliance. COBIT 5 replaces this with no less than 15 ‘goals’, divided into three subdimensions (Intrinsic quality, Contextual and representational quality, and Security/accessibility quality). One of these goals is ‘Appropriate amount of information’. The question raised here is: what is an appropriate amount? Just enough? How realistic is it to imagine that these goals will indeed be used in daily practice? And how and to what extent do they contribute? At what price?

A good addition in COBIT 5, in our view, is that activities are now linked to management practice, rather than to a process. This enables a better understanding of which activities (or ‘controls’) would be expected to be part of the management practice (or satisfy the ‘control objective’). In addition, COBIT 5 now describes the inputs (where does it come from) and outputs (where does it go to) per management practice, which we also see as added value. This provides insight into the requirements for establishing and assessing a management practice, and illustrates the connections between management activities and practices.

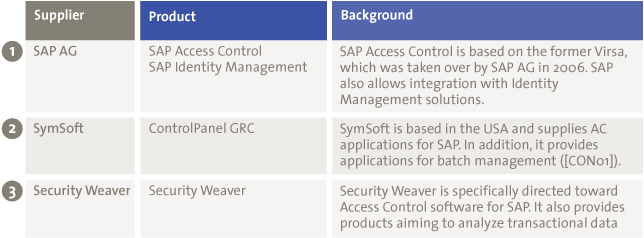

The COBIT 5 product family is also much more extensive than we have seen around COBIT 4.1. Additional publications – so far – include the professional guides ‘COBIT 5 for Information Security’, for ‘Assurance’ and for ‘Risk’. Moreover, approximately ten practical guides on specific topics are currently available. Amongst others, these cover topics such as Vendor Management, Cybersecurity and Configuration Management. Furthermore, specific audit programs have been developed for the processes in the domains of EDM, APO, BAI and DSS (the MEA domain is yet to come). In our view, it is a positive development that additional publications are being released, as these focus on different audiences and usages. They have been in the pipeline for several years however, and similar information has been explained and referred to in different publications, which could lead to confusion if this is not done consistently. However, it is not always easy to keep track of all the publications that are released or of all the links between the contents of all these documents. There is a real risk that all of this will create confusion and people will lose track of developments.

COBIT 5 has also been mapped to other relevant standards and frameworks, which was also the case with the former versions. This mapping has always been and continues to be one of COBIT’s strong points. In COBIT 5, the adoption of the principles and implementation approach of the ISO 38500 standard on Corporate Governance of IT is equally supported. It would be very nice to see the re-appearance of the Mapping Series in one way or another, now with COBIT 5 as the basis, of course.

Rules of Engagement – the fundaments of COBIT 5

In this chapter, we explain a limited number of key elements of COBIT 5: the principles, the goals cascade, and the enablers.

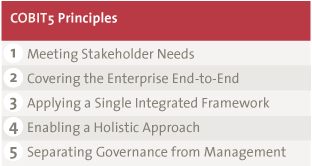

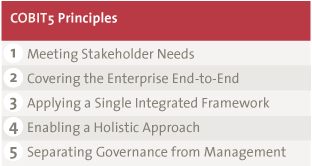

COBIT 5 has been built around five major principles for Governance and Management of Enterprise IT. In conjunction, they should enable an enterprise to build an effective governance and management framework that optimizes information and technology investment and use for the benefit of stakeholders ([ISAC12]).

Figure 3. COBIT 5 principles ([ISAC12]).

- Meeting Stakeholder Needs: organizations exist to add value for their stakeholders. COBIT 5 addresses the needs of stakeholders particularly through the goals cascade, which will be further explained below. The stakeholder needs balance between the realization of most of the benefits, the optimization of risk taking, and the optimization of the use of resources.

- Covering the Enterprise End-to-End: as described earlier, COBIT 5 now aims at bringing together the governance of the enterprise with IT Governance, covering not only the IT department but the entire organization. Information is the key resource that requires governing here.

- Applying a Single Integrated Framework: COBIT 5 aims at being the overarching framework for Enterprise Governance for IT that is linked and based on best practices and other frameworks.

- Enabling a Holistic Approach: COBIT 5 provides a set of enablers that jointly support the implementation of governance and management of Enterprise IT. The enablers are further explained in this chapter.

- Separating Governance from Management: as described in the previous section, COBIT 5 has introduced two levels of processes, for governance and for management. Furthermore, the distinction between the role of both disciplines is made explicit by defining their role and responsibility.

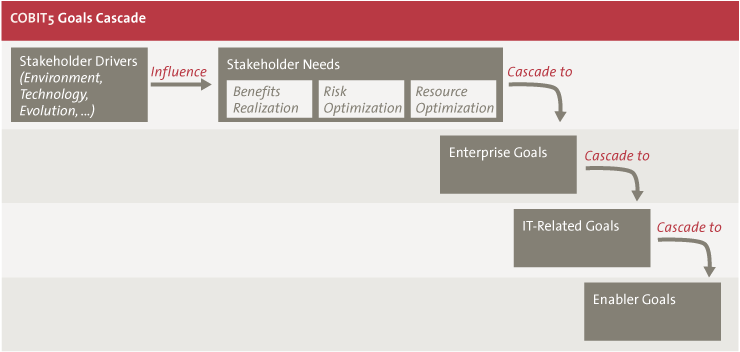

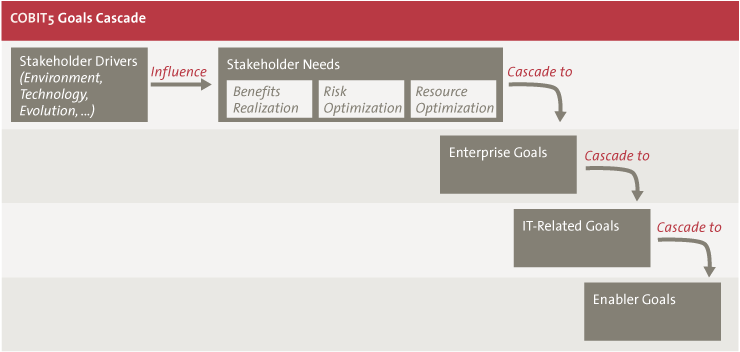

COBIT 5 has defined – based on the existing set of business goals of COBIT 4.1 – 17 enterprise goals and 17 IT-related goals which are structured according to the Balanced Score Card dimensions (Financial, Customer, Internal, Learning & Growth). All enterprise goals are linked to one or more IT-related goals through two types of relationships: Primary (direct contribution to the goal) and Secondary (indirect contribution to the goal). In a next step, the IT-related goals are also linked to one or more of the 37 IT processes with similar relationships. This means that if you know which strategic direction an organization is taking, you can determine the most relevant IT processes or – coming from the other direction – one can easily determine whether a specific process supports one or the other IT goal, and subsequently also the enterprise goal.

Figure 4. Goals Cascade ([ISAC12]).

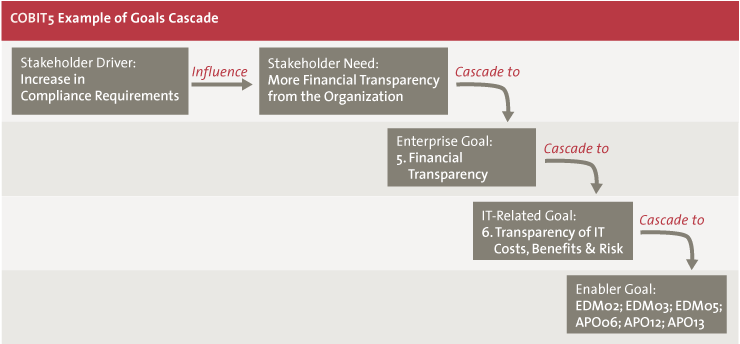

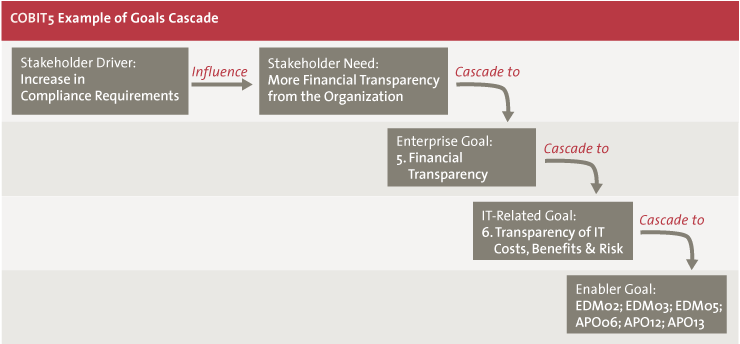

To explain the Goals Cascade in more detail, a relatively straightforward example is presented below.

A company had difficulties in its financial reporting in the past, and its main objective for the next few years was to be financially transparent. This corresponds with the Enterprise Goal number 5 in the framework. Based on the mapping provided, we know that IT-related goal number 6, ‘Transparency of IT costs, benefits and risk’ is linked to the enterprise goal. Following the logic, this results in a set of IT processes most relevant for the organization:

- EDM02 Ensure Benefits Delivery

- EDM03 Ensure Risk Optimization

- EDM05 Ensure Stakeholder Transparency

- APO06 Manage Budget and Costs

- APO12 Manage Risk

- APO13 Manage Security

The above-mentioned processes are described in detail in the COBIT 5 publication ‘Enabling Processes’.

Figure 5. Example Goals Cascade.

The benefit of this structured approach provided by COBIT 5 is that it is relatively easy for any organization to determine the IT strategy and the related IT processes that need to be well in place if the enterprise strategy and goals are clearly defined. Furthermore, this provides direction for the scope of measuring or assessing the quality of the IT processes in place, as this gives insight into how well the enterprise goals are supported by IT. It should be noted that the knowledge of the scope of the processes does not say anything about the capability or maturity of the processes. These have to be assessed before a conclusion can be drawn about how well the IT processes support the respective IT goals and subsequently the enterprise goals.

A potential pitfall could be the explosion of the number of relevant IT processes if multiple enterprise goals are equally important (which is often the case in daily practice). This could quickly lead to the situation where all or almost all IT processes appear to be important. Conscious selection and prioritization are a necessity here.

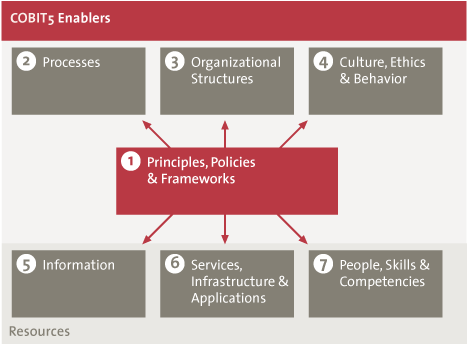

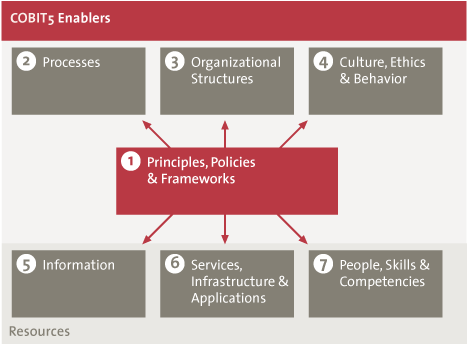

COBIT 5 has defined seven enablers. Enablers are defined as “factors that, individually and collectively, influence whether something will work – in this case, governance and management over enterprise IT” [ISAC12]). The enablers form the key implementation of the principle ‘enabling a holistic approach’. This is translated into the fact that the seven enablers jointly provide more or less all elements relevant to an organization. COBIT 5 recognizes the importance of the interrelation between the enablers: e.g., processes are performed by people, using information and other resources. In its appendix, the COBIT 5 framework provides a high-level overview of the attributes of the seven enablers. However, the only enabler that is truly elaborated in the framework at the moment is the ‘processes’, which has its own dedicated publication.

Figure 5. COBIT 5 Enablers ([ISAC12]).

Has COBIT 5 conquered the world?

In our experience, we have as yet seen little eagerness in organizations to move towards COBIT 5 and adopt the framework. We have come across organizations that have decided not to adopt COBIT 5 in the near future. Several organizations are tending to hold on to COBIT 4.1 and do not see the added value of changing their approach: with regard to their assurance approach or related to maturity assessments of IT processes. We see in particular that organizations have difficulty with the newly added concepts in COBIT 5. Existing COBIT 4.1 processes that have been further detailed out and have changed slightly are not the biggest issue here. Some of the new processes in COBIT 5 are very welcome and we have also seen organizations that are indeed undertaking efforts to establish the new governance processes. However, the capability model and the enablers seem to be too complex to implement directly. ‘Hybrid’ implementation is becoming more and more common: organizations want to use the COBIT 5 processes, but assess them according to the COBIT 4.1 maturity model. In all, the focus seems to remain on processes and their COBIT 4.1 maturity equivalent rather than on any of the new concepts introduced with COBIT 5.

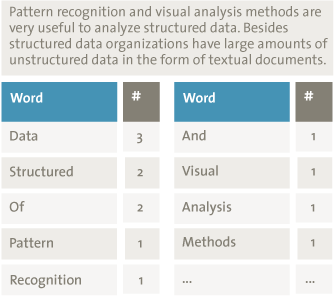

Bartens, De Haes et al. ([Bart14]) also acknowledge the ‘challenging adoption of the framework’ and relate this to its perceived complexity. In their paper, they aim to facilitate its usage and adoption by means of information visualization. This is supported by a developed prototype such as the visualization tool. One can question, however, if a framework for IT and Business specialists that requires a piece of software based on scientific research will actually succeed with regard to adoption and implementation. COBIT 5 was very recently made available in an online version, but it is still too early to draw any conclusions on its acceptance and usage.

Perhaps it is also worth keeping in mind the fact that COBIT was originally developed by a large group of volunteers with a passion for IT and the governance of IT.

COBIT 5 has definitely brought us some additions and advances:

- The capability model for a more objective assessment method.

- Bringing together Enterprise Governance and IT Management could help bridge the gap between governance and IT, to further improve business and IT alignment. Senior Management of an organization could gain further insight in how IT needs to be directed and how it can add value to the business strategy.

- Specific publications such as audit programs and guides for target groups.

- Aligning and linking to different standards, frameworks and legislation improves the ‘one framework for all’ mindset.

- The integration and alignment of COBIT, ValIT, and RiskIT.

- A number of new concepts have been added, but have not yet been worked out in more detail (e.g., the stakeholder needs, the enablers such as organizational structures and culture). Its value is yet to be proven.

But we also see a number of downsides:

- The former maturity model was easy to explain, understand and utilize, although the results of an assessment could contain some subjectivity. The current capability model might be academically more accurate, but it certainly lost some points in practical adoption.

- With the step up to Enterprise Governance, the focus on IT Governance has decreased. The distance between Enterprise Governance of IT and IT Management might be too big to bridge without (aspects of) this layer in-between.

- The additional publications were introduced a long time (up to a few years) after the initial release of COBIT 5, and momentum might have been lost as some have long been eagerly awaited and some still need to be issued.

- The ‘enterprise-wide’ mindset has led to a theoretical and academic approach. The essential question here is: how practical (efficient and effective) is this option for ‘regular’ organizations? Of course, any user still should apply what is useful to a specific situation, but might need some guidance in how to select the COBIT elements.

When we consider the fast-moving IT world, we also wonder how practical the framework will be in newer environments and ways of working. IT is ever-changing and so are the requirements to govern and manage it. How valuable and flexible is COBIT – with all its metrics defined in the processes – for organizations fully committed to traveling the Agile road? How does DevOps fit into COBIT? Can COBIT in its current form be used in such environments as well? This sounds like an interesting challenge, which might very well not be a specific issue for COBIT itself, but a more fundamental aspect regarding the governance model required for these types of organizations. All IT departments and teams need governing and management, and it would be interesting to further investigate how new business and IT models and methodologies fit within the concepts of COBIT. The challenge for ISACA will be to see how its COBIT 5 framework can cooperate with other methodologies and existing frameworks, such as Lean, DevOps and Agile, and the extent to which COBIT 5 can assist in introducing governance, management and control into these situations.

COBIT 5: conclusions

In our view, ISACA might face some tough challenges in the (near) future. One aspect is the branding and marketing of COBIT 5, as the current framework no longer fits its name although this name is widely known and recognized. Another aspect might be that the framework has grown too complex, and ISACA may have overreached itself in its aim to cover all relevant elements. Bringing it back in line with its essentials and focusing on providing guidance to organizations to establish and improve their governance and management of IT by using COBIT and by using ‘business language’ would no doubt be a useful step forward. A third aspect might be to reinstate the maturity model. And a fourth might be to bring order and consistency to the flood of COBIT 5 documents. Our wish list also displays updated versions of the well-received Mapping Series, which were a great help in bridging the gap between COBIT and other more specific frameworks.

In our opinion, it is too early to conclude that COBIT 5 is a bridge too far. There is still hope of success because of all the good and useful things it can offer. COBIT is and remains a very valuable aid in the management and governance of IT. It is important not to merely follow and ‘implement’ the framework blindly, but to use common sense and experience to select those elements that are applicable to an organization or a specific situation, depending on the circumstances.

Although the bridge is far (but not too far), those that follow the right track and stay focused will cross that bridge one day and reach their objective(s), even if they encounter obstacles on their journey. It is important to realize that COBIT 5 is not a goal in itself but a means, and it will certainly provide a very substantial amount of help and assistance. It is also a very comfortable feeling to know that COBIT 5 is a stable and robust bridge and not just some light suspension bridge somewhere in a jungle. It is not a giant leap forward – it is more of an evolution than a revolution – but it allows organizations to take substantial steps towards better governance and management of IT.

As this article represents our view on COBIT 5, we thought it would be interesting to include the perspectives and insights of three subject-matter experts closely related to COBIT and ISACA. We have interviewed Marc Vael, Erik van Eeden and Steven De Haes.

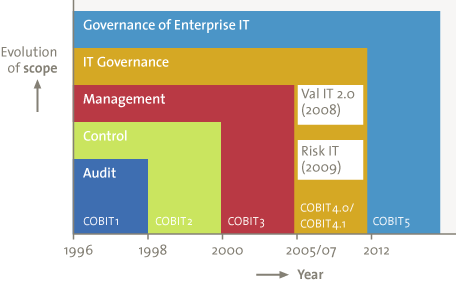

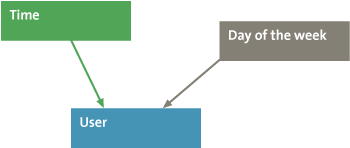

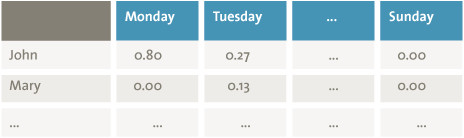

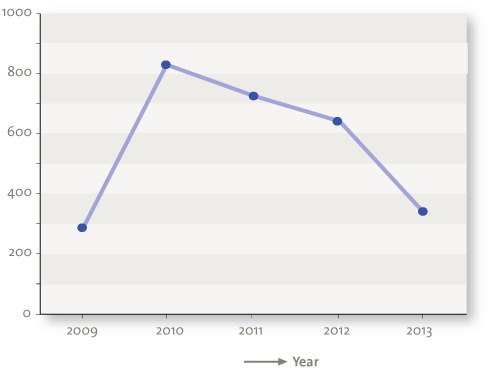

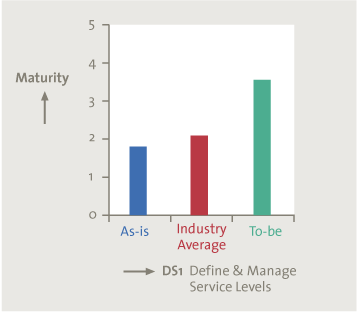

KPMG has developed the IT Assessment Tool providing a structured approach that supports the maturity assessment of IT processes based on COBIT 4.1. It is fully aligned with the goals cascade through the Enterprise and IT Goals. By scoring 6 generic attributes per process, one can determine to what extent the enterprise goals are being met. Organizations are categorized by industry sector (43 in total) and country (64 in total), but also by annual turnover and IT budget. The tool consists of more than 1300 assessments. The COBIT maturity model together with the assessment database allows for interesting benchmarking possibilities. The maturity of the IT processes of organizations can be compared with that of their peers. This is something that adds value for and can be understood by (IT) Management.

Because of the challenges described in this article on the adoption of COBIT 5, the capability model of COBIT 5 and the trend of ‘hybrid’ use of COBIT (using the COBIT 4.1 maturity model of to assess the COBIT 5 processes), the tool is still based on the COBIT 4.1 framework.

References

[Bart14] Yannick Bartens, Steven de Haes, Linda Eggert, Leonard Heilig, Kim Maes, Frederik Schulte and Stefan Voß, A Visualization Approach for Reducing the Perceived Complexity of COBIT 5, in: Advancing the Impact of Design Science: Moving from Theory to Practice, M.C. Tremblay, D. VanderMeer, M. Rothenberger, A. Gupta, and V. Yoon, (eds.), Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp. 403-7.

[Bart15] Yannick Bartens, Steven de Haes, Yannick Lamoen, Frederik Schulte and Stefan Voß, On the Way to a Minimum Baseline in IT Governance: Using Expert Views for Selective Implementation of COBIT 5, proceedings of 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2015.

[Haes09] S. De Haes and W. Van Grembergen, Moving From IT Governance to Enterprise Governance of IT, ISACA Journal, Vol. 2009, No. 3, p. 21, 2009.

[ISAC12] ISACA, COBIT 5 – A Business Framework for the Governance and Management of Enterprise IT, 2012.

Interview with Marc Vael CISSP CISA CGEIT CRISC CISM

Interviewers: Dirk Bruyndonckx and Salvi Jansen

Marc Vael is Chief Audit Executive at Smals, a Belgian not-for-profit IT company with 1,800 employees that implements IT solutions for Belgian Federal Social Security Institutions. He is responsible for all internal auditing activities reporting to the Audit committee. Marc has three Master’s Degrees (Applied Economics, Information Management and IT Management) and certifications in IT audit (CISA), information security (CISM, CISSP), IT risk management (CRISC), IT governance (CGEIT, ITIL service manager) and project management (Prince2). He achieved his official certification as Board Director at GUBERNA in 2012.

Marc has 22 years’ active experience and is passionate about evaluating, designing, implementing and monitoring solutions with regard to risk and information security management, continuity/disaster recovery, data protection/privacy, and IT Audit. He is a frequent speaker at international conferences and at meetings with boards of directors. Currently, Marc is also president of the ISACA Belgium chapter, associate professor at Antwerp Management School, Solvay Brussels School and TIAS, deputy member of the Flemish Privacy Commission, member of the Permanent Stakeholder Group of ENISA, and he is active as director on several boards.

Moving from COBIT 4.1 to COBIT 5, how has the framework evolved?

A first major novelty and strong point of the COBIT 5 framework is the focus on the strategic layer of the company, both at board level and executive committee level. By defining these different layers, the process of establishing who needs to take up which role on process controls in an organization becomes more transparent. The RACI matrices have improved, and are a transparent visual way of setting responsibilities.

Second, the seven enablers are an important point of reference, certainly for auditors: are these domains under control or not? But also for all managers: have we covered the basic components and/or have we viewed the topic from all seven angles before taking a decision? Two of the seven enablers are specifically hard to capture/audit: Culture, Ethics and Behavior and Competences & Skills. However, in reality, these are just as important as the other five, and this is correctly reflected in the framework.

How do you use COBIT 5?

COBIT 5 is a source of inspiration. As it comprises all relevant themes, it can be used as a checklist to see if all required elements are part of your audit. Some themes are addressed very clearly, such as innovation, whereas others are much more subtle, such as privacy, and are spread across the different elements of the framework.

When setting and maintaining the scope of an initiative based on COBIT, it is also very important to define which themes are explicitly out of scope. Otherwise, you run the risk of scope creep, and the audit program can become too extensive. Implementing COBIT as a whole is a frequently made mistake, it is unrealistic.

Work programs are meant as guidance, and I never copy them directly into an audit initiative. COBIT is an international framework and therefore a compromise, one should only take from it what is strictly needed. It should not be the only source of inspiration of the audit: other frameworks can provide additional insights.

A recommendation I always give is to select at least one process from the governance layer (EDM), one from the monitoring process (MEA), and one from each management process (APO, BAI, DSS). This forms an essential baseline for the audit.

Can COBIT 5 be used for new trends?

COBIT 5 can be introduced to make people reflect on certain topics, such as cloud computing, Bring Your Own Device or Internet of Things. It also helps users to remain in control when evaluating and implementing these initiatives. Difficulties arise when talking to people who are heavily involved in technical implementation. They find the wordings used in the framework too holistic, whereas management is able to connect instantly to the terminology.

I try to avoid introducing COBIT 5 as yet another framework on top of other frameworks such as ITIL, ISO, TOGAF and other methodologies. The content supersedes these specific methods: use it as a point of reference, white-label if necessary. Where ITIL, ISO and TOGAF might have taken too many topics in scope of their framework, COBIT 5 will refer explicitly to these more specific frameworks to avoid becoming too heavy. This is quite unique.

About which COBIT 5 concepts would you caution people?

The Capability Model to score the different enablers is downright depressing. Especially when coming from a Maturity Model, this method of evaluation can bring a score of 3 or 4 out of 5 down to just 1 out of 5. Even though the new scoring model is meant to improve the objectivity of the rating, it can be really hard to defend in front of anyone. There is no problem in using COBIT 5 with the scoring model of COBIT 4.1, certainly when a link with risk management has been established, and the maturity levels are coupled to risk scales within the company.

Second, the way each enabler of the framework is implemented tends to vary. For Services, Infrastructure & Applications, the work programs are about specific topics such as SharePoint and DB2, but for Culture, Ethics and Behavior the existing documentation is very limited. When addressing People, Skills and Competencies, the US model and EU model for competence rating differ, so people will have to choose when setting up their audit initiative.

Third, when your focus is on governing the IT function itself, instead of providing assurance over the Governance of Enterprise IT, you might still be better off using the COBIT 4.1 Assurance Guide instead of the COBIT 5 version. The focus has indeed shifted to the corporate governance aspects of IT.

Has COBIT 5 been able to make the link with general corporate governance considerations?

The corporate governance bodies in many organizations are still giving much attention to their usual topics of strategy, finance, marketing, HR, etc., where IT is still not on their agenda despite the innovative angle and added value, except in case of major IT investments or major IT issues. IT and therefore also COBIT are still at risk of remaining an immaterial topic for the board, even when their responsibilities are clearly set out within the framework.

There is an important link with the monitoring processes (EDM and MEA). Apart from the operational monitoring and reporting, there is a second line of reporting that should enable progressive insight in how the organization is doing, and of course improvement in the long term. The board could use this reporting to identify trends and define actions in its annual report.

COBIT can function as the bridge between the business and the IT environment in any organization, multinational or small.

Could adoption be increased by providing a ‘light’ version as was done for COBIT 4.1?

COBIT 4.1 indeed featured a COBIT Quick Start Guide. However, the requirements in each industry make it hard to scope down. Financial sector requirements are highly focused on compliance, requiring a large scope, whereas a governmental context today requires a focus on a ‘Lean’ approach.

COBIT 5 is no longer one publication, but multiple volumes addressing different themes and functions. It is ISACA’s duty to keep an overview and internal coherence of the publications, whereas the reader is encouraged to take from it what is essential to him. There is not one company that has fully implemented ITIL, ISO27001 or TOGAF, and this should not be an ambition for COBIT.

The complete COBIT offering is mostly known to auditors and trainers, whereas other professionals will select specific topics and use it as a checklist or benchmark. As the governance processes (EDM) gain traction, executive support will increase, we hope. Work programs have been published for these new processes, but we still need to work on bringing them to the market through hands-on cases.

How does the target audience evolve?

Whereas previous COBIT versions were targeted mainly at the audit function (the third line of defense), the COBIT 5 series also targets the second line of defense: the quality, risk, security and compliance functions. This is done either through specialized editions of COBIT, i.e., COBIT 5 for Assurance, COBIT 5 for Security, or by specific work programs around topics such as DevOps, Lean, privacy, etc.

For these functions, COBIT 5 might be a viable alternative to operational frameworks such as ITIL and ISO27001, which might become too technical for these profiles. At the same time, these oversight functions need a lot of operational information, in which COBIT 5 could help.

Pressure is building on auditors to give advice too, and experience teaches us that people from the field are in fact most suited to become an auditor on the same matter. I would advise firms to give operational people the possibility to take up an auditing role, while maintaining independence of course. Rotations could be performed at each strategic cycle, which is about 4 to 5 years. When returning to the business, these profiles are then able to reason with a controls perspective and provide deep insight into the subject matter. This practice is known to be performed even at executive committee level.

Finally, COBIT 5 truly attempts to provide useful information for executives and board members.

Any final considerations?

The IT environment has grown too big and is evolving too fast for any auditor to remain an expert in all IT elements. It pushes auditors and all other oversight functions to specialize in specific topics and collaborate with others in order to get a complete view of IT controls in an organization. COBIT 5 helps maintain an overview, add value, and reduce risk.

I would strongly advise people to use the COBIT 5 publications to inspire people within the organization on all sorts of IT-related topics during decision-making or assessment phases, without mentioning that you are using COBIT 5: focus on applying the COBIT 5 content.

Interview with Erik van Eeden MIM MBA RI

Interviewer: Pieter de Meijer

Erik van Eeden joined the board of the ISACA Netherlands chapter in mid-2014. In his role as board member, he is responsible for the ISACA training program provided in the Netherlands. A large step has been taken in this area by the addition of the CRISC and CGEIT courses to the program. Other training courses currently on his wish list include the COBIT Implementation and COBIT Assessor program. Erik has been active in the IT sector, where he started his career at AkzoNobel among others, since 1982. After a number of years at Getronics he made a career switch in the year 2000, and has been active as an independent advisor and trainer ever since, with several non-profit roles added. Erik is above all an accredited COBIT 5 trainer. In addition, he lectures in the field of IT Management (ITIL v3, BiSL, ASL2), system development, testing, and the Scrum methodology.

What do you think of the COBIT 5 Framework?

An important development with COBIT 5 is that the framework and the assessment model have become more mature. There are now official COBIT 5 training courses available through APMG, where both the trainers and the institute providing the courses are required to be accredited. Everything is organized more strictly nowadays. You could say that it is remarkable that ISACA has not gone one step further as yet: why can’t you obtain a COBIT-certified title that can be compared with CISA and CISM? Currently, I would not be able to provide any numbers of COBIT professionals in the Netherlands.

In my opinion, the naming and the structure of the capability model for processes in COBIT 5 have become much stronger than they used to be. The capability model is definitely more objective and provides both the assessors and the organization with something to hold on to. The current model is also somewhat more rigid than the maturity model from COBIT 4.1, as one now needs to do a solid job even to get to level 1. In my experience, getting to a higher maturity level is sometimes challenging for Dutch organizations, as they seem to struggle with implementing roles, such as the ‘governing body’. They prefer to put an organization in place instead. However, this is an essential part of COBIT.

I can imagine that people who examine COBIT 5 for the first time find it overwhelming. I see a similarity with ITIL v3 here. The trick is to break things up into smaller pieces so that you can see how they fit in the bigger picture. Actually, this means that, without a training or special course, you will have difficulty with applying this. I see an increase in interest in COBIT 5 training from ITIL professionals, who regard this as a useful addition to their skill set. Besides these, the training group normally consists of both internal staff as well as external advisors and professionals. And, of course, there are several IT managers.

How do you value the adoption of COBIT in the Netherlands so far?

We have noted that, in the Netherlands, the adoption of COBIT 5 has lagged behind our expectations somewhat. A part of this can be explained by the fact that, with COBIT 5, we have headed in the direction of Governance of Enterprise IT, whereas the naming of the framework does not fit this focus. On the other hand, the name ‘COBIT’ is recognized by many a people from the past as the framework for control objectives, while that is no longer quite so clearly addressed. Actually, I think COBIT is in some sort of identity crisis.

At ISACA, we want to use the coming period to organize roundtables to further discuss and explain COBIT 5. Furthermore, I think it is ridiculous that our own ‘C-professionals’ [meaning the ISACA members holding a certification – ed.], have so little knowledge of COBIT 5 at present. I don’t think this is a typical Dutch problem, as we see that adoption is also slow outside our country.

Another cause is that the term ‘Governance’ is a vague concept for many aspects. That also contributed to the fact that the development of COBIT 5 took much time and effort. I always stress the fact that IT Governance cannot exist without the business. Furthermore: Governance can never be a goal in itself, but is always a means to lead the company better.

Fortunately, I also see examples of organizations that have properly embedded IT Governance in real-life practice. Achmea is a good example of this, with a well-organized governing body that steers and directs the IT department. I once raised the question: “Don’t you feel uncomfortable with someone looking over your shoulder?” The simple answer was: “I’ve been accustomed to this from the start.” This means that the culture of the organization plays an important role here as well.

Hasn’t COBIT 5 grown too big?

I would like to make the comparison with ITIL version 3. After its release, there was a similar response. What you then saw was that the ISM method was developed under the leadership of Jan van Bon. In fact, this is an ‘ITIL Light’ and was based on version 2 of ITIL in a more practical manner. Maybe COBIT 5 requires something similar? ISACA has an article describing a minimum of processes, a sort of COBIT 5 Light.

And a next step? In my view, COBIT 6 will only surface when more organizations actually improve their governance. Then the other ‘enablers’, such as culture, will receive more attention, rather than IT processes exclusively.

I think that ISACA must keep on exploring its own limitations, with a special emphasis on collecting existing best practices and incorporating them in the approach. COBIT 5 has already built upon various frameworks and all these models help the user achieve a higher level with his organization. For example, the ISO standard helps assessment in an objective way.

What I personally would like to see added to COBIT is the topic of ‘testing’. It would be interesting to link the level and extent of the test approach of IT Products to its added value to the enterprise goals.

All in all, I think COBIT is a very powerful tool. Our challenge lies especially in communicating it to a wider audience!

About ISACA

ISACA was founded in 1967 by professionals described as those “auditing controls in the computer systems that were becoming increasingly critical to the operations of their organizations”, and later transformed into the Information Systems Audit and Control Association. Nowadays simply known as ISACA, it has over 115,000 members in the broad range of IT, spread over 180 countries.

Next to the development, improvement and maintenance of COBIT, the organization provides a number of valued certifications, including CISA, CISM, CRISC and CGEIT.

Events, research and education are organized through local chapters, among other means, ensuring an annual revenue of well over 40 million dollars in conjunction with membership fees.

http://www.isaca.org/

Interview with Steven De Haes PhD

Interviewer: Dirk Bruyndonckx

Steven De Haes PhD is Associate Professor Information Systems Management at the University of Antwerp – Faculty of Applied Economics and at the Antwerp Management School. He is actively engaged in teaching and applied research in the domains of Digital Strategies, IT Governance & Management, IT Strategy & Alignment, IT Value & Performance Management, IT Assurance & Audit and Information Risk & Security. He is alumnus of the International Teacher’s Program (Kellogg School of Management) and teaches at bachelor, master and executive level. He also acts as Academic Director for the Executive Master of IT Governance & Assurance, the Executive Master of Enterprise IT Architecture, the Executive Master of IT Management and the (full-time pre-experience) Master in Management.

He held positions of Director of Research and Associate Dean Master Programs for the Antwerp Management School. He also acts as speaker and facilitator in academic and professional conferences and coaches organizations in their digital strategies, IT governance, alignment, value and audit/assurance efforts. He is involved in the development of the international IT governance framework COBIT as researcher and co-author.

How do you look back on COBIT 5, three years after its release? And how do you look forward?

When we talk about COBIT, we are talking about the professional field of IT Governance, i.e., the control and management of technology. If you look at the past 10 years, and certainly before the release COBIT 5, the IT governance discussion was all too often a debate for and by IT professionals. This was the case in the academic world as well as in the business world. If you entered into a discussion about IT Governance, you were quickly sent to the IT department and the CIO, especially if you spoke with business people. IT Governance was regarded as a matter far removed from their activities. In the world of science there was a strong conviction that the concept of IT Governance needed to be taken out of IT’s own little corner. Today we speak of the Enterprise Governance of IT in both the scientific world and common business practice. Now the business has pride of place. This has resulted from the changed point-of-view that, within a highly digitized enterprise, the responsibility over IT has become an integral part of the responsibility of the business. This is no more than logical, in view of the fact that the business itself has been digitized and automated to a large extent. The processes are digitized, the company has been digitized, the revenue model is based on technology etc., so the business must assume its responsibilities and can no longer just delegate that responsibility to IT. This evolution has been very strongly extended and stretched in COBIT 5.

What about IT Governance itself, because that seems to have disappeared from the map, although many people are still using the term? The current distance between Enterprise Governance of IT and IT itself is too big. Does IT need ‘something’ to govern itself and to bridge the distance between the two?

COBIT 5 has built a complex layer placed on top of the IT Management processes, and this complex layer – the Enterprise Governance of IT layer – is about involvement in and steering of the IT function by the business. But if we look at many organizations, the entire structure starts with a minimum maturity of the IT organization itself. If we do not have that minimum maturity, it is an illusion to think that IT will be capable of talking to the business. Business people complain all too often that even that minimum maturity is not present: IT is too slow, there are complaints about helpfulness, the IT Helpdesk is not working properly etc. These complaints are very operational because that is what people experience every day, and they actually have very little to do with the discussion on Enterprise Governance of IT. But it is essential for the broader discussion that these kinds of basic processes are working at a reasonably mature level. It is important to note that these basic processes are still provided by COBIT, but it does have that extra layer placed on top.

In its early days and until recently COBIT was – and probably still is – mainly seen as something that could be used by IT. In COBIT 5, however, the link with the business and business management is very prominent in certain processes. It is often very difficult for the CIO to enter into discussions with the business. He gets a framework that says he has to talk to the business on areas such as portfolio management, investment analysis, business impact analysis, etc., but the party is often deaf to what he says or does not understand him as he seems to use a different language.

COBIT 5, however, phrases this completely correctly. If we want to construct the bridge from IT to the business and if we want to create value from IT, the business people should occupy the IT driving seat, setting out the direction for the CIO. But this is not a situation we come across very often. In practice, there is still a big barrier to overcome: how do we get the business people around the table to take up this debate in a constructive way. Most of all, this requires IT to be properly organized and to be doing a good job. And by extension on the other side: the Board of Directors must be part of this story as well. This top-down commitment is very important – but often lacking.

Structural improvements in the governance and management of IT are seen especially in those companies where the CEO believes very strongly in this story and imposes this belief from the top: the business gives direction to IT. This cannot happen in only a few months and may even take several years, but the tone at the top of the business is very important in this matter. Of course, if the incident-management process and the functioning of the Help Desk are not working well, then obviously you can hardly expect from the business that it will steer what is regarded as IT commodity.

Governance responsibilities are matters that need to originate from the Board of Directors and Executive Committee – top down – and COBIT also defines it this way: “Enterprise Governance of IT is the responsibility of the highest governing bodies.” This raises the big problem that only too often there is inadequate and/or insufficient awareness to take up this role appropriately. Despite the fact that companies have been digitized and automated to a large extent (and this ranges from banks to hospitals), we see that the appropriate knowledge of digitization and automation is often insufficient at top level.

We have obviously encountered all kinds of IT Management processes in our various duties in the past, but the surrounding framework – the former IT Governance – is still required before you can rise to the Enterprise Governance of IT level. You can hardly expect from the Board of Directors or from the Executive Committee that they will assist in setting up processes, but they should be aware of the contribution of IT to the creation of business value.

Let us take portfolio management as an example. Portfolio management is about prioritizing business investments, usually with an IT component. In essence this deals with transformations: the improvement of business processes that ultimately also make use of technology. But it is up to the business to prioritize the investment portfolio, based on its financial value drivers such as ROI, IRR, etc. IT is essentially not involved in this. IT is not the owner of these budgets, these budgets are the property of the business. It can even be called an aberration that the portfolio management process is organized by IT, because this is fundamentally a completely wrong setup.

In practice, however, it almost always happens this way and, in large and important improvement and transformation projects, it will very often be senior IT staff that need to pull the business people onboard. The business will almost never do this spontaneously by itself. And if it does, it often occurs in companies where the current CEO previously performed a CIO role, and thus has an affinity with IT and is ‘IT-savvy’. But if that is not the case, then the CIO and senior IT people should use proper, comprehensible language to try to haul the business people onboard in the hope that they will gradually become the owner of the portfolio management process, as it also ultimately concerns their own budgets. IT should actually have no budget of its own for projects, but solely for IT commodity affairs.

COBIT 5 is also trying to appeal to different target groups, especially the business world. This is a big change compared to the past.

COBIT has extended its target audience to include business people, because these should take control of IT. This is a big challenge for ISACA, because this new target is not the natural target of ISACA and COBIT, as established over the past 20years. ISACA must also learn to speak the language of this new audience in its framework.

Perhaps this exercise should start from listening to the business and its problems and challenges with IT rather than from starting with COBIT as such. If the business wants to realize and achieve all this in order to assume its new role, it will need to organize itself. Fortunately there is something that can help it do this: COBIT. The point is to present the issues in an easily understandable language and transparent manner for the business. Speaking the same language is imperative if one wants to get this new audience onboard and to realize alignment between business and IT. Throwing the COBIT books onto the CEO’s table is most likely not the correct method.

Mature IT organizations are important, but COBIT 5 no longer uses maturity, now preferring capability. This has already provoked quite a few discussions. In practice, there is little understanding of why ISACA took this decision. Everyone reaches back to COBIT 4.1 maturity, with its comprehensible scale of 1 to 5, where most companies would not even reach a capability level of one in COBIT 5.

Much ink has indeed already been spilled on this topic. It is very unfortunate that maturity, as such, has disappeared because maturity is a perfect management tool for internal improvement. It is easy to use, reproducible, etc. Maturity was easy to understand and to comprehend, but the concept was perhaps not always robust enough. For improvement projects, it was a perfect tool, especially for IT Management.

A strong feature of the Process Assessment Model (PAM) is that it is a much more robust model to assess processes. It also uses a scale from 0 to 5, but under much stricter ‘rules’ than the maturity assessment. This makes PAM extremely suitable for conducting very thorough and detailed process audits. It does contain the risk, however, that most processes would not even reach a capability level of 1. Capability improvement projects are much harder to realize, and generally consume a lot more resources and time.

There is a strong yearning to return to the maturity model, especially in the management world. This should indeed be reinstated, and a way must be found to enable both to exist side by side. The capability model clearly has its benefits for the world of audit, external assurance and other accreditations because it is a reasonably robust method. But for management, maturity measurements are essential. ISACA should therefore again include the maturity model in the COBIT framework. Actually, the 4.1 model – including Val IT – is still widely used (the generic attributes, process attributes. etc.) and it is mainly for the new COBIT 5 processes that extensions should be drafted at the process level. Actually PAM and capability are not new concepts to COBIT 5, as they already existed in COBIT 4.1, besides the inherent maturity scale. We must definitely abandon the idea that maturity is not good, while the market is not even asking for capability. You may not end up comparing the two, because it would be comparing apples and oranges. Of course they both have a scale of 0 to 5, which could easily lead to confusion.

In the better known Capability Maturity Model (CMM-I) of the SEI (Software Engineering Institute) both scales – capability and maturity – co-exist but here, too, the concept of capability is totally different from the one in COBIT 5. With CMM-I there is an official process to get certified – which in itself is not an easy task – and there is a great distinction with COBIT 5 and PAM whereby levels are not attributed at the level of individual processes as discussed here, but to coherent sets of processes. Same story, totally different thing.

I think that ISACA nurtured a plan to certify organizations in a way similar to the issue of an ISO 15504 certificate, and that this necessitated a robust assessment method such as PAM. Maturity, AS IS and TO BE have much value for the internal organization, but are less suited to the outside world as the level of interpretation is greater than those with the more objective capability, making the latter a better tool for external reporting. However, COBIT is mainly used and designated for internal use and the improvement of the IT organization. During recent discussions within the COBIT Growth Task Force, one of the recommendations was indeed to integrate the maturity model within COBIT once again.

Is COBIT, as an acronym, the correct name if you want to involve and reach a different kind of audience?

Here you have to give a nuanced answer. The name of COBIT is strong, especially in the world of IT Audit, Assurance, IT professionals, etc. But it remains new to many people, even within IT. ISACA thinks COBIT is better known than reality actually shows. As long as business people think that it is something to do with IT, it will not gain ground with them. The term ‘digital’, however, does work. In short, a different language is required for COBIT to enter the world of business people.

ISACA should also change the name COBIT?

The name has its advantages and disadvantages. The term ‘COBIT implementation’ does not sound good to me. I think that one cannot implement COBIT as such. COBIT is a very good book with many suggestions, but is generic by definition. You have to take out the things that are interesting and useful for your organization, and you should then also translate these into the organization’s specific context. You can implement and improve governance and management processes, but you cannot implement COBIT. You can think long and hard about how you are going to tackle this, or you can be inspired by a book that has been there for 20 years covering this issue. It contains some very useful suggestions. COBIT is just a tool, and is not perfect, but very usable. Ultimately it is not about COBIT, but about better processes and structures.

If you look at the current and new slogans and hypes like Scrum, Lean, social media, DevOps, Big Data etc., to what extent is COBIT 5 more or less suited to accommodate these?

Management of technology is about the management of processes and structures. Whether you look at social media or the Cloud or Big Data, it should actually make no difference. COBIT is about management content that should be applied in a permanent and sustainable way.

And whether we have another technology next year and the following year another hype, that is of lesser importance. But you do have to have structures and processes in the organizational management that look at that technology and also ask what that technology can do for the company. Only then should you decide whether or not to jump on the wagon. To COBIT, it should make no difference. Scrum is a type of example different from the social media because Scrum is more of a development method that is close to the business. It works in an iterative way, which could prove valuable in today’s Agile and proactive business environments. Scrum fits well within COBIT because Scrum is actually full of management controls and management structures. You can also look at it with other methodologies and frameworks, but I think the COBIT model covers best the responsibilities of the IT, and also provides the most widespread coverage. I still have to come across another model that is so broad. There is simply nothing else on that level.

Then we come to the next question, COBIT 5 enablers and drivers …?

That’s where I think the evolution of COBIT 6 lies. The enablers model in itself is very good, but they have made it a little too complex. The process enabler is the most important one. You have 37 processes in COBIT 5, and also my own research shows that the processes are not only the most difficult but also the most important in the design of the organization. If we look at successful cases, these are typically cases where they have a good process-based approach to portfolio management, strategy etc. The structures are a second key enabler. But we do not have much on structures in COBIT 5. To me, COBIT should be able to provide generic advice on, for example, an IT Steering Committee or the job description of a CIO, and so on. If we managed to put in COBIT 5 generic enterprise goals and IT goals that are very intuitive for many companies, we could also make a generic CIO job description. There is both a big need for, and a big interest in, things like this. We have also a major need for guidance on the soft side of IT Governance (skills, expertise, awareness) and how to deal with it.

In any case, the process enabler is well developed. There is also something about the information enabler but, to my knowledge, that is little used, and the others have not yet been developed. What I think COBIT 6 should be – and that will not be tomorrow – is that it should not evolve into 37 processes, but into 37 areas of responsibility. Much of the information required for this (e.g., process, practices, activities, etc.) already exists, but should be developed in such a way that it can be used in a very practical way (e.g., the use of the enablers). In short, COBIT 6 should be a simplification around 37 areas of process description, structural description and a description of other relevant elements.

I believe very strongly that there will be a COBIT 6 within a few years. Now the processes are already well developed, and I think that the practice also calls for a concrete manifestation of the other enablers. There is already a lot of material: the 7 enablers have been developed for Assurance, Information Security and Risk but, at some point, you are going to have to aggregate all of this in a generic knowledge base. Then it should be possible to filter all of that information, depending upon your needs. This has actually been done in specific publications, but you really have to go searching and puzzling to muster all the relevant information. So it is not really user-friendly, hence the need for simplification. Now, if you want to prepare yourself, you must look into the generic process guide and you should also consult other books and publications. Sometimes these even contradict each other to a certain extent. There should be a simple model of 37 areas of responsibility and, for each of those areas, you require a structure and processes. In my opinion, that’s the way to go.

How do you see the acceptance and use of COBIT in Belgium? And subsequently: are the IT auditors following the path of COBIT 5 or do they keep hanging on to COBIT 4.1 for good reasons?

I think it depends on the audience. When I look at the audit, risk and compliance assurance audience, it is actually very widespread. If I look at the business community, which I think is a very important community for the further development around alignment and value creation in IT, the spread is extremely low. When I teach business people, such as financial managers, operations managers, marketing managers, it is very much unknown. A third audience is IT management; there it is still not as widespread as I would expect. In the Belgian market, things such as ITIL and Prince2 are very well known and used, and often one has notions of COBIT, but the actual use of COBIT in their organization is not so ubiquitous. There is much potential for growth because simply no other framework offers such a wide coverage at that level. And that is not a value judgment of the other frameworks, on the contrary. COBIT is not too selfish to refer to other methodologies and that’s just one of its particular merits.

A final word to conclude our conversation?

COBIT has some limitations, you should use it with a critical mind, it is not perfect but it is very useful. I try, from my academic basis, to introduce COBIT more and more into the academic world, which is good for the acceptance of the framework. Do not misunderstand me, I do not organize COBIT courses. I use COBIT very often, but I start from concepts around business strategies, IT strategies and others from within the academic world, and only then do I refer to COBIT as a tool and I explain how it works. It makes no sense to give a purely theoretical presentation of COBIT, the most important aspect is the idea itself and the concept behind it.