This article looks at new developments in sustainability reporting on a global and European level. A global multi-stakeholder acknowledgment for coherence and consistency in sustainability reporting is desired. Major standard setters are collaborating and prototyping what later can become a unified solution. In this paper we share what we know about the proposal of EU CSRD, EU Taxonomy and IFRS ISSB and try to indicate in what way companies should be ready for new global and European developments.

Introduction

Regardless of regulation and domicile, companies – both public and private – are under pressure from regulators, investors, lenders, customers and others to improve their sustainability credentials and related reporting. Companies often report using multiple standards, metrics or frameworks with limited effectiveness and impact, a high risk of complexity and ever-increasing cost. It, moreover, can be daunting to keep track of the everchanging reporting frameworks and new regulations.

As a result, there is a global demand for major stakeholders involved in sustainability reporting standard setting collectively coming up with a set of comparable and consistent standards ([IFR20]). This would allow companies to ease reporting fatigue and prepare for compliance with transparent and common requirements. Greater consistency would reduce complexity and help build public trust through greater transparency of corporate sustainability reporting. Investors, in turn, would benefit from increased comparability of reported information.

However, the demand for global coherence and greater consistency in sustainability reporting is yet to be met. This paper provides an overview of the current state of affairs and highlights the most prominent collaborative attempts to set standards, through the IFRS Foundation Sustainability Standards Board, EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and EU Taxonomy.

Global sustainability reporting developments: IFRS International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) in focus

The new International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) aims to develop sustainability disclosure standards that are focused on enterprise value. The goal is to stimulate globally consistent, comparable and reliable sustainability reporting using a building block approach. With strong support from The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), a rapid route to adoption is expected in a number of jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions, the standards will provide a baseline either to influence or to be incorporated into local requirements. Others are likely to adopt the standards in their entirety. Companies need to monitor their jurisdictions’ response to the standards issued by the ISSB and prepare for their implementation.

There is considerable investor support behind the ISSB initiative, and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for net Zero (GFANZ) announced at COP26 that over $130 trillion of private capital is committed to transforming the global economy towards net zero ([GFAN21]). Investors expect the ISSB to bring the same focus, comparability and rigor to sustainability reporting as the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB Board) has done for financial reporting. This could mean that public and private organizations will adopt the standards in response to investor or social pressure.

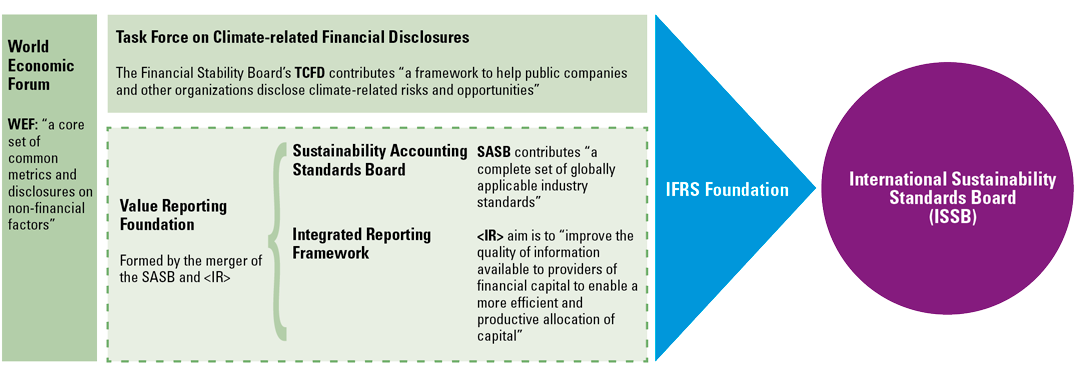

ISSB has provided prototype standards on climate-related disclosures and general requirements for sustainability disclosures, which are based on existing frameworks and standards, including Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). As for now the prototype standards have been released for discussion purposes only. The prototypes cover climate-related disclosures and general requirements for disclosures that should form the basis for future standard setting on other sustainability matters.

Figure 1. What contributes to the ISSB and IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The prototypes are based on the latest insight into existing frameworks and standards. They follow the four pillars of the TCFD’s recommended disclosures: governance, strategy, risk management, metrics and targets. Enhanced by climate-related industry-specific metrics derived from the SASB’s 77 industry-specific standards. Additionally, the prototypes embrace input from other frameworks and stakeholders, including input from the IASB Board’s management commentary proposals. The ISSB builds prototypes using a similar approach to IFRS Accounting Standards. The general disclosure requirements prototype was inspired by IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements, setting out the overall requirements for presentation under IFRS Accounting Standards.

Companies that previously adopted TCFD should consider identifying and presenting information on topics other than climate and focus on sector-specific metrics, while those companies that previously adopted SASB should focus on strategic and process-related requirements related to governance, strategy and risk management.

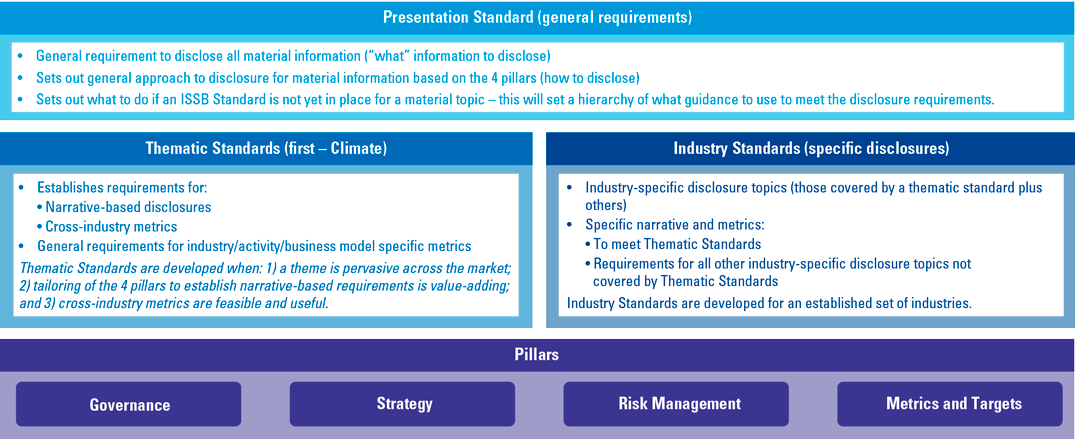

Figure 2. How Sustainability Disclosure Standards are supposed to look. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The prototypes shed light on the proposed disclosure requirements. Material information should be disclosed across presentation standard, thematic and industry-specific standards. Material information is supposed to:

- provide a complete and balanced explanation of significant sustainability risks and opportunities;

- cover governance, strategy, risk management and metrics and targets;

- focus on the needs of investors and creditors, and drivers of enterprise value;

- be consistent, comparable and connected;

- be relevant to the sector and the industry;

- be present across time horizons: short-, medium- and long-term.

Material metrics should be based on measurement requirements in the climate prototype or other frameworks such as the Greenhouse Gas Protocol.

The climate prototype has a prominent reference to scenario analysis. Such analysis can help investors assess the possible exposures from a range of hypothetical circumstances and can be a helpful tool for company’s management in assessing the resilience of a company’s business model and strategy to climate-related risks.

What is scenario analysis?

Scenario analysis is a structured way to consider how climate-related risks and opportunities could impact a company’s governance framework, business model and strategy. Scenario analysis is used to answer ‘what if’ questions. It does not aim to forecast of predict what will happen.

A climate scenario is a set of assumptions on how the world will react to different degrees of global warming. For example, the carbon prices and other factors needed to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. By their nature, scenarios may be different from the assumptions underlying the financial statements. However, careful consideration needs to be given to the extent in which linkage between the scenario analysis and these assumptions is appropriate.

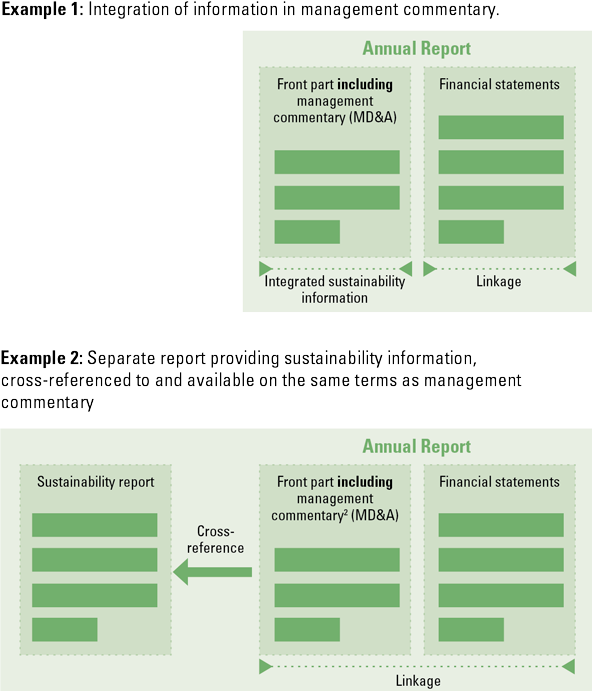

The prototypes do not specify a single location where the information should be disclosed. The prototypes allow for cross referencing to information presented elsewhere, but only if it is released at the same time as the general-purpose financial report. For example, the MD&A (management discussion & analysis) or management commentary may be the most appropriate place to provide information required by future ISSB standards.

Figure 3. Examples of potential places for ISSB-standards disclosure. [Click on the image for a larger image]

As for an audit of such disclosure, audit requirements are not within the ISSB’s remit. Regardless of local assurance requirements, companies will need to ensure they have the processes and controls in place to produce robust and timely information. Regulators may choose to require assurance when adopting the standards.

How the policy context of the EU shapes the reporting requirements

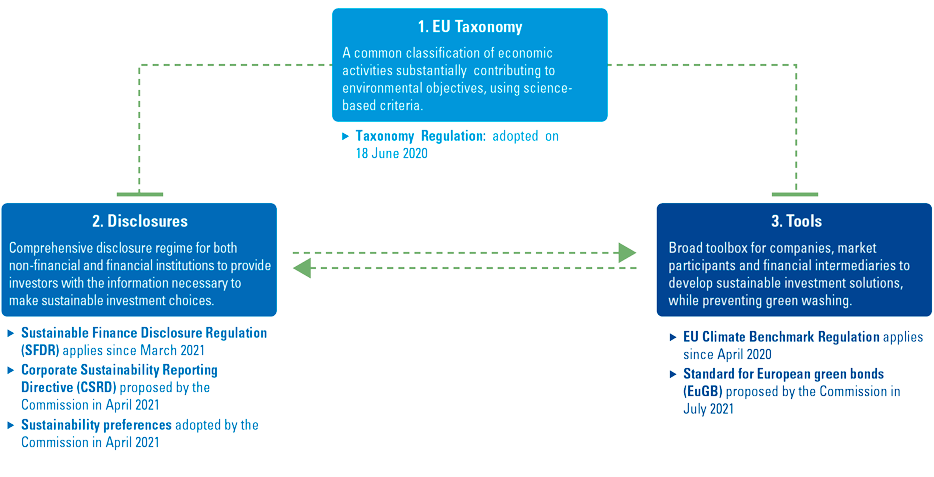

In line with the Sustainable Finance Action Plan of the European Commission, the EU has taken a number of measures to ensure that the financial sector plays a significant part in achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal ([EUR18]). The European policy maker states that better data from companies about the sustainability risks they are exposed to, and their own impact on people and the environment, is essential for the successful implementation of the European Green Deal and the Sustainable Finance Action Plan.

Figure 4. The interplay of EU sustainable finance regulations. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The following trends build up a greater demand for transparency and uptake of corporate sustainability information in investment decision making:

- Increased awareness that climate change will have severe consequences when not actively addressed

- Social stability requires more focus on equal treatment of people, including a more equal distribution of income and financial capital

- Allocating capital to companies with successful long-term value creation requires more comprehensive insights in non-financial value factors

- Recognition that large corporate institutions have a much broader role than primarily serving shareholders

The European Commission as a policy maker addresses these trends through comprehensive legislation focusing on directly addressing issues as well as indirectly addressing issues through corporate disclosures to support investors decision making.

In terms of the interplay between the European and global standard setters, it is interesting to notice that collaboration is highly endorsed. The EU Commission clearly states that EU sustainability reporting standards need to be globally aligned and aims to incorporate the essential elements of globally accepted standards currently being developed. The proposals of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation to create a new Sustainability Standards Board are called relevant in this context ([EUR21d]).

Proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

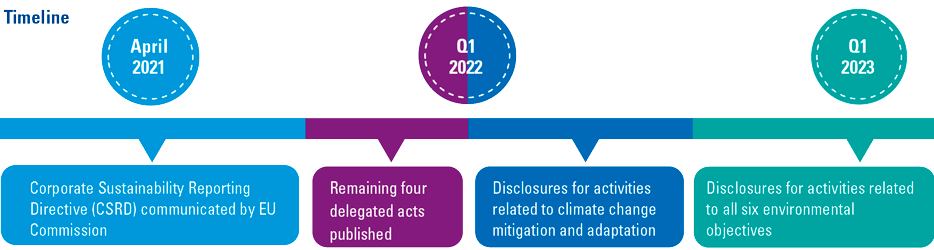

On April 21, 2021, the EU Commission announced the adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in line with the commitment made under the European Green Deal. The CSRD will amend the existing Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and will substantially increase the reporting requirements on the companies falling within its scope in order to expand the sustainability information for users.

Figure 5. European sustainability reporting standards timeline. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The proposed directive will entail a significant increase in the number of companies subject to the EU sustainability reporting requirements. The NFRD currently in place for reporting on sustainability information, covers approximately 11,700 companies and groups across the EU. The CSRD is expected to increase the number of firms subject to EU sustainability reporting requirements to approximately 49,000. Small and medium listed companies get an extra 3 years to comply. Criteria to define the applicability of CSRD to companies (listed or non-listed) make a list of three. At least two of three should be met. The criteria are:

- more than 250 employees and/or;

- EUR 40 mln turnover and/or;

- EUR 20 mln assets.

New developments will come with significant changes and potential challenges for companies in scope. The proposed Directive has additional requirements that will affect the sustainability reporting of those affected ([EUR21a]):

- The Directive aims to clarify the principle of double materiality and to remove any ambiguity about the fact that companies should report information necessary to understand how sustainability matters affect them, and information necessary to understand the impact they have on people and the environment.

- The Directive introduces new requirements for companies to provide information about their strategy, targets, the role of the board and management, the principal adverse impacts connected to the company and its value chain, intangibles, and how they have identified the information they report.

- The Directive specifies that companies should report qualitative and quantitative as well as forward-looking and retrospective information, and information that covers short-, medium- and long-term time horizons as appropriate.

- The Directive removes the possibility for Member States to allow companies to report the required information in a separate report that is not part of the management report.

- The Directive requires exempted subsidiary companies to publish the consolidated management report of the parent company reporting at group level, and to include a reference in its legal-entity (individual) management report to the fact that the company in question is exempted from the requirements of the Directive.

- The Directive requires companies in scope to prepare their financial statements and their management report in XHTML format and to mark-up sustainability information.

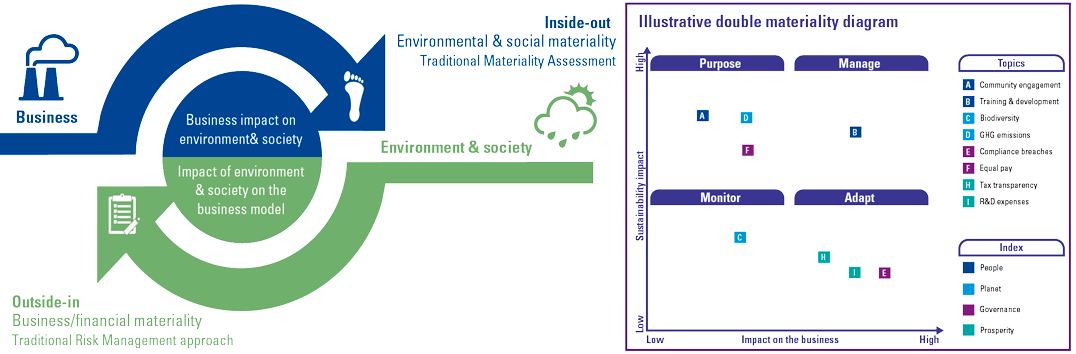

Figure 6. Nature of double materiality concept. [Click on the image for a larger image]

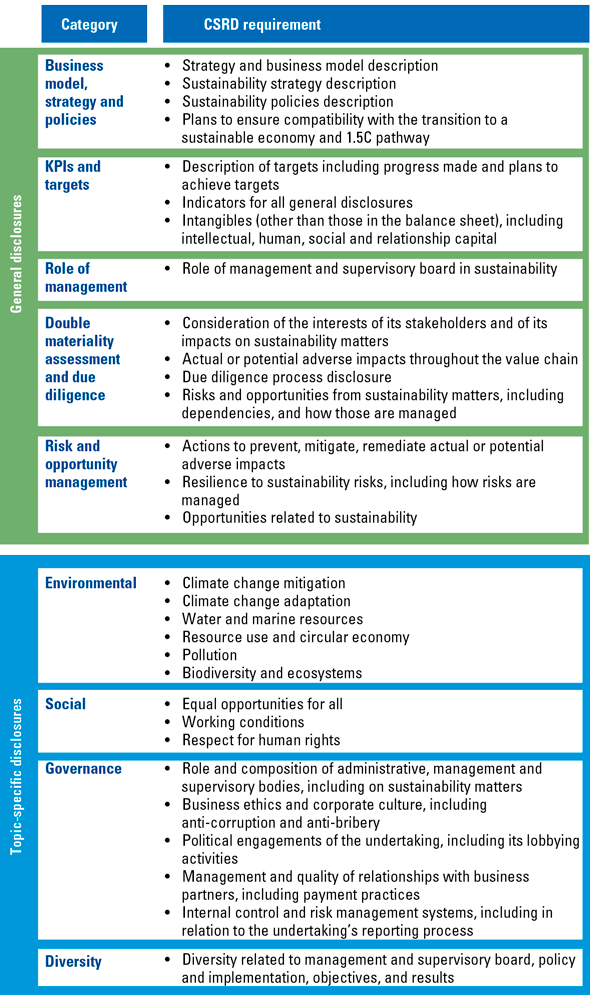

The CSRD has overall requirements on how to report, general disclosure requirements on how the company has organized and managed itself and topic specific disclosure requirements in the field of sustainability. It should be noted that the company sustainability reporting requirements are much broader than climate risk, e.g., environmental, social, governance and diversity are the topics addressed by the CSRD.

Figure 7. Overview of the reporting requirements of the CSRD. [Click on the image for a larger image]

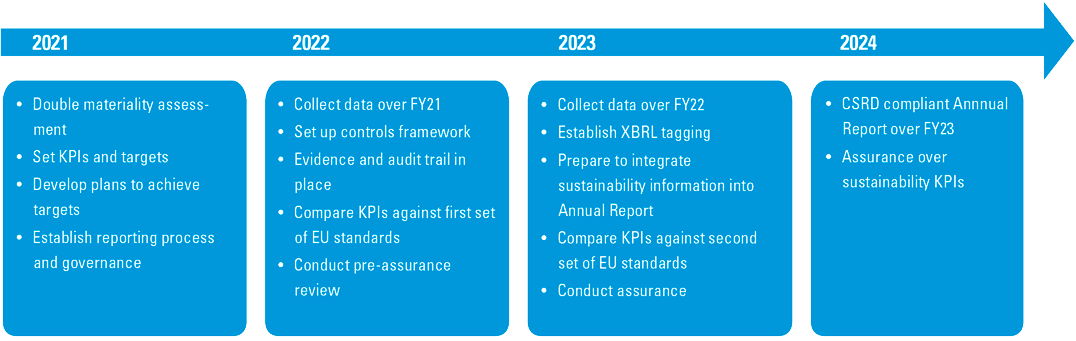

Extended reporting requirements that come with the CSRD may require companies in scope of this regulation to start preparing now. Here is an illustrative timeline for companies to become CSRD ready.

Figure 8. A potential way forward to become CSRD ready. [Click on the image for a larger image]

EU Taxonomy – new financial language for corporates

The EU Taxonomy and the delegated regulation are the first formal steps of the EU to require sustainability reporting in an effort to achieve the green objectives.

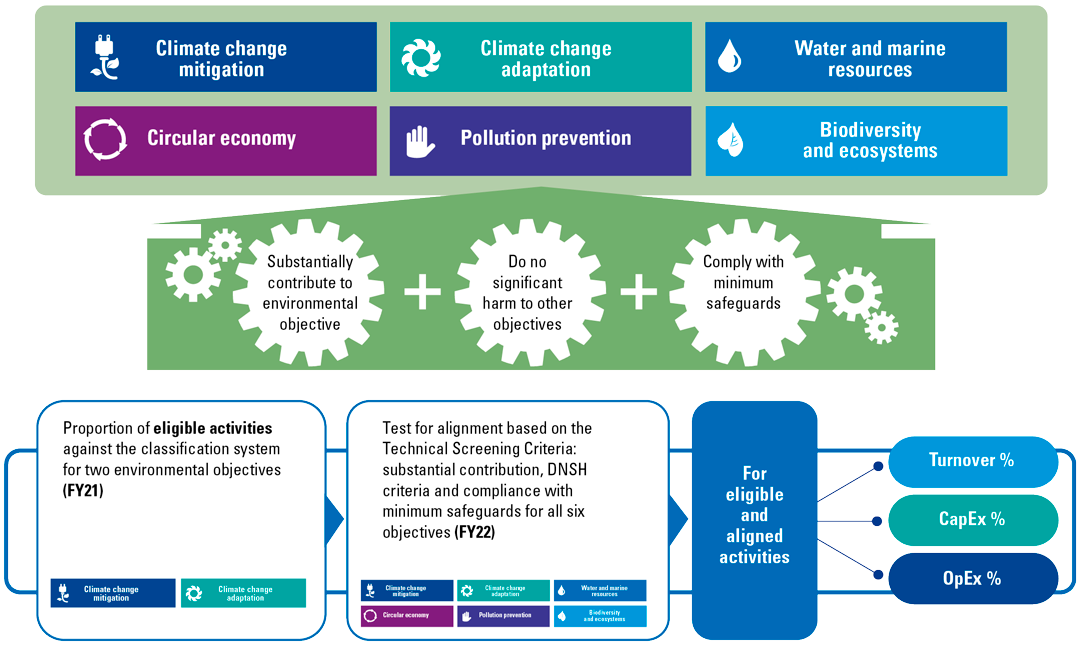

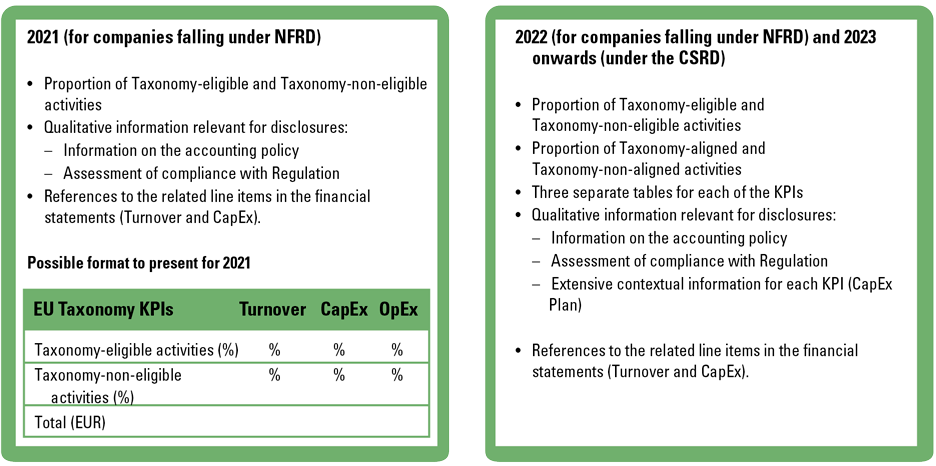

Over the financial year 2021, so called large (more than 500 employees) listed entities have to disclose, in their non-financial statement as part of the management report, how their turnover, CapEx and OpEx are split by Taxonomy-eligible activities (%) and Taxonomy-non-eligible activities (%) including further qualitative information.

Over the financial year 2022 these activities need to be aligned with the criteria for sustainability to contribute to the environmental objectives and do no significant harm to other objectives and comply with minimum safeguards. Alignment should then be reported as proportion of turnover, CapEx and OpEx to assets or processes associated with economic activities that qualify as environmentally sustainable. To financial institutions in turn it translates to the requirement to report on the green asset ratio, which in principle is a ratio of Taxonomy-eligible or Taxonomy-aligned assets as a percentage of total assets.

Figure 9. EU Taxonomy timeline. [Click on the image for a larger image]

The “delegated act” under the Taxonomy Regulation sets out the technical screening criteria for economic activities that can make a “substantial contribution” to climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation. In order to gain political agreement at this stage texts relating to crops and livestock production were deleted, and those relating to electricity generation from gaseous and liquid fuels only relate to renewable, non-fossil sources. On the other hand, texts on the manufacture of batteries and plastics in primary form have been added, and the sections on information and communications technology, and professional, scientific and technical activities have been augmented.

With further updates of the technical screening criteria for the environmental objective of climate mitigation we will also see the development of the technical screening criteria for transitional activities. Those transitional economic activities should qualify as contributing substantially to climate change mitigation if their greenhouse gas emissions are substantially lower than the sector or industry average, if they do not hamper the development and deployment of low-carbon alternatives and if they do not lead to a lock-in of assets incompatible with the objective of climate- neutrality, considering the economic lifetime of those assets.

Moreover, those economic activities that qualify as contributing substantially to one or more of the environmental objectives by directly enabling other activities to make a substantial contribution to one or more of those objectives are to be reported as enabling activities.

The EU Commission estimates that the first delegated act covers the economic activities of about 40% of EU-domiciled listed companies, in sectors which are responsible for almost 80% of direct greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. A complementary delegated act, expected later in early 2022, will include criteria for the agricultural and energy sector activities that were excluded this time around. The four remaining environmental objectives — sustainable use of water and marine resources, transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems — will be addressed in a further delegated act scheduled for Q1 of this year.

Figure 10. EU Taxonomy conceptual illustration. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Companies shall disclose the proportion of environmentally sustainable economic activities that align with the EU Taxonomy criteria. The European ([EUR21c]) Commission views that the translation of environmental performance into financial variables (turnover, CapEx and OpEx KPIs) allows investors and financial institutions in turn to have clear and comparable data to help them with their investment and financing decisions. The main KPIs for non-financial companies include the following:

- The turnover KPI represents the proportion of the net turnover derived from products or services that are Taxonomy aligned. The turnover KPI gives a static view of the companies’ contribution to environmental goals.

- The CapEx KPI represents the proportion of the capital expenditure of an activity that is either already Taxonomy aligned or part of a credible plan to extend or reach Taxonomy alignment. CapEx provides a dynamic and forward-looking view of companies’ plans to transform their business activities.

- The OpEx KPI represents the proportion of the operating expenditure associated with Taxonomy-aligned activities or to the CapEx plan. The operating expenditure covers direct non-capitalized costs relating to research and development, renovation measures, short-term lease, maintenance and other direct expenditures relating to the day-to-day servicing of assets of property, plant and equipment that are necessary to ensure the continued and effective use of such assets.

The plan that accompanies both the CapEx and OpEx KPIs shall be disclosed at the economic activity aggregated level and meet the following conditions:

- It shall aim to extend the scope of Taxonomy-aligned economic activities or it shall aim for economic activities to become Taxonomy aligned within a period of maximum 10 years.

- It shall be approved by the management board of non-financial undertakings or another body to which this task has been delegated.

In addition, non-financial companies should provide for a breakdown of the KPIs based on the economic activity pursued, including transitional and enabling activities, and the environmental objective reached.

Figure 11. EU Taxonomy disclosure requirements. [Click on the image for a larger image]

As for challenges companies face when preparing for EU Taxonomy disclosure, the following key implementation challenges are observed in our practice:

- administrative burden and systems readiness;

- alignment with other reporting frameworks and regulations;

- data availability;

- definitions alignment across all forms of management reporting;

- integration of EU Taxonomy reporting into strategic decision making.

Furthermore, the Platform on Sustainable Finance is consulting ([EUR21b]) on extending the Taxonomy to cover “brown” activities and a new Social Taxonomy. The current Taxonomy covers only things that are definitely “green”, indicating a binary classification. The Platform notes the importance of encouraging non-green activities to transition and suggests two new concepts – “significantly harmful” and “no significant harm”. The aim of a Social Taxonomy would be to identify economic activities that contribute to advancing social objectives. A follow-up report by the Commission is expected soon. The eventual outcome will be a mandatory social dictionary, which will add further to the corporate reporting requirements mentioned above and company processes and company-level and product disclosures for the buy-side (see below). It will also be the basis for a Social Bond Standard.

Conclusion

Evolution of sustainability reporting is happening at a fast pace. Collective efforts on a global and European level help develop the disclosure requirements to make them more coherent and consistent in order to be comparable and reliable. The prototype standards that have been released by now show optimism about leveraging on the existing reporting frameworks for the sake of consistency. Luckily the European and global standard setters prioritized recycling and leveraging on existing reporting frameworks and guidance instead of designing something absolutely new to the wider audience. Sustainability reporting standardization is after all not only much waited activity but also very much a dynamic and multi-centred challenge. All, EU CSRD, EU Taxonomy and IFRS ISSB will ultimately contribute to the availability of high-quality information about sustainability risks and opportunities, including the impact companies have on people and the environment. This in turn will improve the allocation of financial capital to companies and activities that address social, health and environmental problems and ultimately build trust between those companies and society. This is a pivotal moment for corporate sustainability reporting; more updates on the developments will follow most certainly!

Read more on this subject in “Mastering the ESG reporting and data challenges“.

References

[EUR18] European Commission (2018). Communication from the Commission. Action Plan: Financing Sustainable growth. Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52018DC0097

[EUR21a] European Commission (2021). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No537/2014, as regards corporate sustainability reporting

[EUR21b] European Commission (2021). Call for feedback on the draft reports by the Platform on Sustainable Finance on a Social Taxonomy and on an extended Taxonomy to support economic transition. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/210712-sustainable-finance-platform-draft-reports_en

[EUR21c] European Commission (2021). FAQ: What is the EU Taxonomy Article 8 delegated act and how will it work in practice? Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/sustainable-finance-taxonomy-article-8-faq_en.pdf

[EUR21d] European Commission (2021). Questions and Answers: Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive proposal. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_21_1806

[GFAN21] GFANZ, Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (2021). Amount of finance committed to achieving 1.5º C now at scale needed to deliver the transition. Retrieved from: https://www.gfanzero.com/press/amount-of-finance-committed-to-achieving-1-5c-now-at-scale-needed-to-deliver-the-transition/

[IFR20] IFRS Foundation (2020). Consultation Paper on Sustainability Reporting. Retrieved from: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/project/sustainability-reporting/consultation-paper-on-sustainability-reporting.pdf

[IOSC21] IOSCO (2021). Media Release IOSCO/MR/16/2021. Retrieved from: https://www.iosco.org/news/pdf/IOSCONEWS608.pdf