The internal audit function plays an important role within the organization to monitor the effectiveness of internal control on various topics. In the current data-driven era we are living in, it will be hard to argue that internal control testing can be done effectively and efficiently by manual control testing and process reviews. Data analytics seems to be the right answer to gain an integral insight into the effectiveness of internal controls, and spot any anomalies in the data that may need to be addressed. Implementing data analytics (audit analytics) within the internal audit function is however not easily done. Especially international organizations with decentralized IT face challenges to successfully implement audit analytics. At Randstad we have experienced this rollercoaster ride, and would like to share our insights on which drivers for success can be identified when implementing audit analytics. In the market we see a large focus on technological aspects, but in practice we have experienced that technology might be the least of our concerns.

Data Analytics within the internal audit

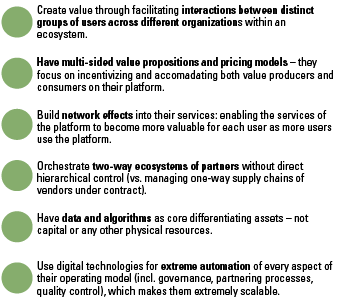

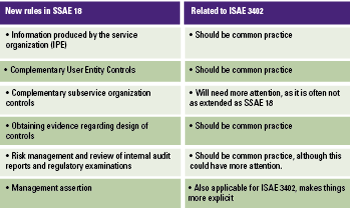

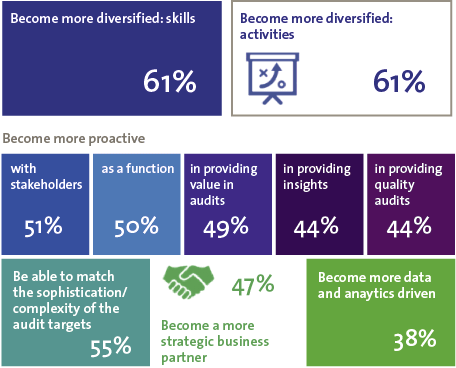

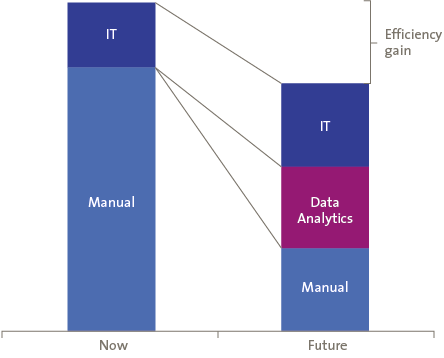

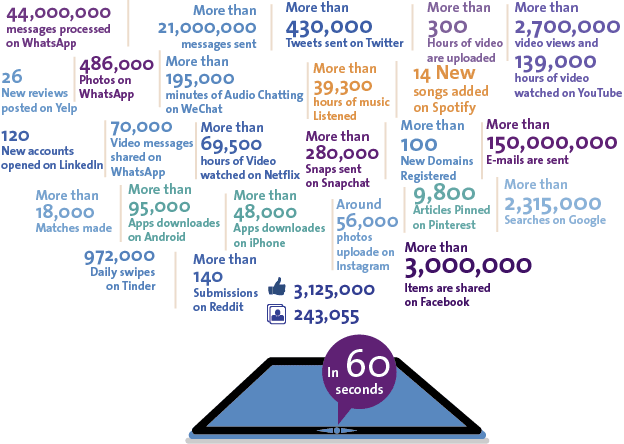

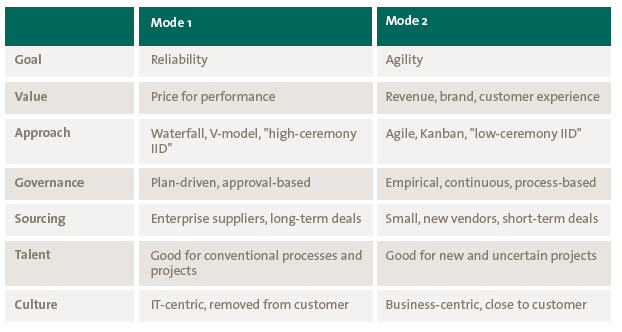

The key benefits in performing data analytics within the internal audit function are predominantly:

- more efficiency in the audit execution;

- cover more ground in the audit executions;

- create more transparency and more basis for audit results/findings.

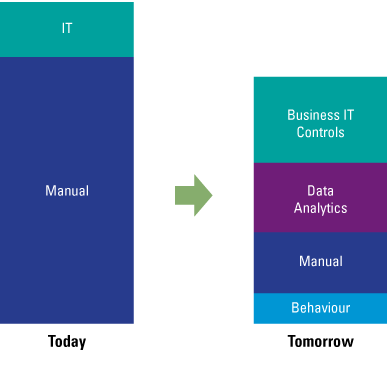

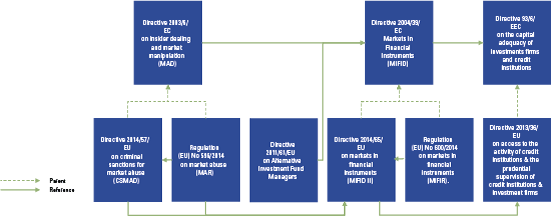

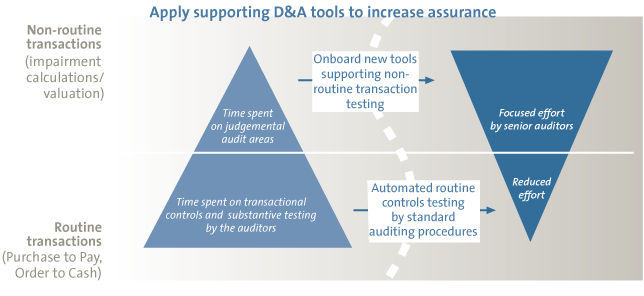

Figure 1. Classical internal audit control testing vs. control testing and data analytics. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Introduction: Audit Analytics, obvious benefits

As an example, we would like to ask you this question: what is the main topic during seminars, conferences concerning data analytics? What is most literature about? How is the education system (e.g. universities) responding?

Chances are your response will involve technology: you read about great tooling, data lakes, the need for you to recruit data analysts and, very important, you must do it all very quickly.

However, the biggest challenge is not technology. The IT component is obviously important, but it is ill-advised to consider the implementation of audit analytics to be just about technology.

Of course, we are not here to argue with the fact that technology is a very important driver to enhance the capabilities of the auditor. The benefits of being able to run effective data analytics within the internal audit function are obvious. The same seminars will usually underline these benefits as much as they can: data analytics in the audit will provide the auditor with more efficiency in his work, and will enable him to cover more ground in the audit executions. Moreover, the auditor will be able to create more transparency and basis for audit results towards the business.

Rightly so, the benefits are obvious, and it seems easy enough to implement. These benefits are well known within the audit community. The benefits are however usually based on the premise of having a good technological basis as the key to success. One could hire a good data analyst and build an advanced analytics platform, and just go live. In some cases, this could work, reality is, however, more challenging.

In most cases more complex factors play a pivotal role in the success of audit analytics, which are not easily bypassed by just having a good data analyst or a suitable analytics platform. Factors that most corporate enterprises must deal with are, for example:

- a complex corporate organization (internationally oriented and therefore different laws, regulations and frameworks, decentralized IT environment and different core processes);

- the human side of the digital transformation that comes with implementing audit analytics;

- integrating the audit analytics within the internal audit process and way of working.

The success of really transforming the internal audit function to the internal audit of tomorrow is where data analytics is embedded in the audit approach, and a prerequisite of gaining insights into the level of control and the effectiveness thereof with the auditee’s organization.

This success we are talking about is currently perceived as a ‘technical’ black box. In our opinion this black box is not only of technological nature, but has a lot more complexities added to it. In this article, we tend to open this black box and offer some transparency based on the experiences we have gained in setting up the internal audit analytics function.

To do this, we will start to describe the experiences we have gained in setting up audit analytics. Based on our story, we will outline our key drivers for success, regarding the implementation of audit analytics. Furthermore, we will move in to detail on how these drivers influence each other, and the importance of a balancing act between the drivers.

Case study: how the Randstad journey on Audit Analytics evolved

In 2015, Randstad management articulated the ambition to further strengthen and mature the risk and audit function. The risk management, internal controls and audit capabilities were set up years before. Taking the function to the next level meant extending existing capabilities and perspectives, with the intent not only to ensure continuity, but also to increase impact and added value to the organization. Integrating data analytics into the way of working for the global risk and audit function was identified as one of the drivers for this.

To set up the audit analytics capability, several starting points were defined:

- build analytics once, use often;

- in line with the organization culture, the approach has to be pragmatic: it will be a ‘lean start-up’;

- the analytics must be ‘IIA-proof’;

- security and privacy have to be ensured;

- a sustainable top down approach, rather than datamining and ad hoc analytics.

This meant that a structured approach had to be applied, combined with the willingness to fail fast and often. In the initial steps of the process, technical experts were insourced to support the initiative in combination with process experts. With a focus on enabling technical capabilities, projects were started to run analytics projects in several countries, and in parallel develop technical platforms, data models and analytics methodologies.

With successes and failures, lots of iterations, frustrations and, as a result, lessons learned, this evolved into a comprehensive vision and approach on audit analytics covering technology, audit methodology, learning & development and supporting tooling & templates. Yet at the same time, it resulted into an approach, which is in line with the organizational context, fit for its purpose, and general requirements, such as GDPR.

Yet at the same time, the results of the analytics projects and contribution to audits showed interesting and promising results: by the end of 2017 a framework of 120 analytics was defined, out of which 65 were made available through standard and validated scripts.

Drivers for successful Audit Analytics

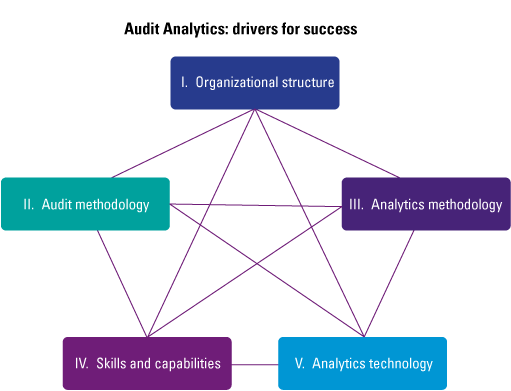

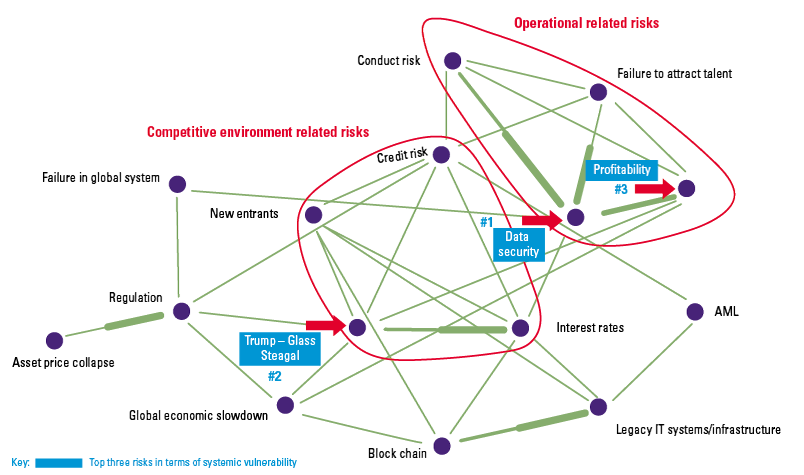

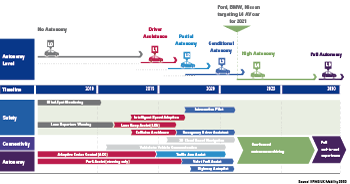

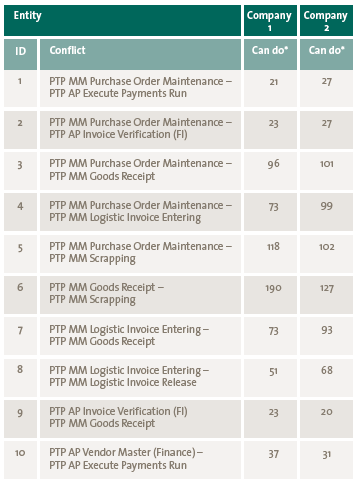

Looking back at the journey and summarizing the central perspective, a model emerged identifying drivers for successful audit analytics. The journey the Randstad risk & audit function has gone through, addressed challenges in five categories: organizational fit, internal organization of the audit analytics, supporting technical tooling and structure, audit methodology alignment and integration and skills, capabilities and awareness.

At different times in the journey, different types of challenges emerged. For example, when Randstad started expanding methodologies and technologies, the next challenge became the fit and application within the organizational context. This in turn translated into developments in the audit analytics organization. Then, the human component became a point of attention, translating into addressing audit methodology alignment and related skills/capabilities. In turn, this was further supported by updating the technical structures. During our journey it became clear to us that these challenges where not individual of nature, but are interacting with each other, and form an interplay of success drivers.

Next, we will go through the five identified challenges in more detail, and illustrate what this means in the Randstad context. In the following chapter we will try to transform these challenges into an early model, that will be the starting point in understanding which drivers have an impact on the success of audit analytics.

Implementing Data Analytics: key drivers for success

In the previous chapter, we discussed how Randstad experienced the implementation of audit analytics and the challenges and learnings that have been gained over the years. In this chapter we will further dissect the identified challenges, and translate them into drivers for success in implementing audit analytics.

Organizational fit

The first question one might want to ask before setting up an analytics program is: ‘how does this fit within the organizational structure?’. The organizational structure is something that cannot be changed overnight, and yet it will greatly determine how your data analytics program must be set up. In case this isn’t thought through carefully in the setup phase of audit analytics, one might encounter an organizational misfit regarding choices that have been made concerning technology or analytics governance. We will outline the key factors that will have an impact on the way audit analytics has to be set up:

- centrally organized versus decentralized organization;

- diverse IT landscape regarding key systems versus a standardized IT infrastructure;

- many audit topics versus a high focus on a few specific audit topics;

- uniform processes among local entities versus divers processes among local entities;

- similar law, regulations and culture versus a diverse landscape of law, regulations and culture;

- aligned risk appetite versus locally defined risk appetite.

We do not perceive the organizational structure as a constant that cannot be changed, but as something that cannot be greatly influenced in order to set up the analytics organization. Therefore, one must consider how the analytics organization can best fit the overall organizational structure, rather than the other way around. The lessons learned regarding this challenge are that it is vital to assess how the organizational structure may impact your methodology and setup for audit analytics. This can have both huge technical as procedural implications on setting up your audit analytics organization.

Audit analytics organization

The way the audit analytics organization is set up, is also a key driver for success. There are a lot of choices one can make when setting up the organizational structure, and defining the roles and responsibilities within the analytics or audit team. The key decision is perhaps whether or not you want to carve out the analytics execution and delegate this to a specialized analytics team, or whether you want to assign the role of data analyst to the auditor himself. This decision will have a great impact on a lot of other things that have to be considered when setting up a data analytics program. Other key factors that we have identified in setting up the analytics organization:

- central data analyst team versus analytic capability for the local auditor;

- a central data analytics platform or a limited set of local tooling;

- separate development, execution and presentation versus generic skillset.

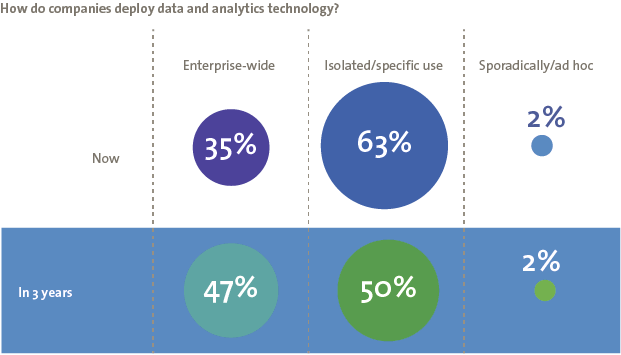

Audit analytics technical structure

The third key driver we mention is the technical structure that will enable the auditors to execute the data analytics. As said in the introduction, this topic usually plays a central role at seminars, conferences and literature about data analytics. In our opinion it is one of many drivers for success, and not necessarily the most important one. Decisions that have been made earlier in the previous two drivers will have a big impact on what choices one should make in this area. Areas to consider are:

- implementing a central platform or work with local tools;

- implementing an advanced data analytics platform versus choosing low entry data analytics tooling;

- using advanced data visualization tools or using low entry visualization tools.

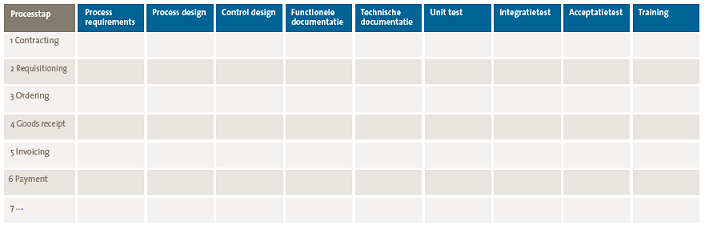

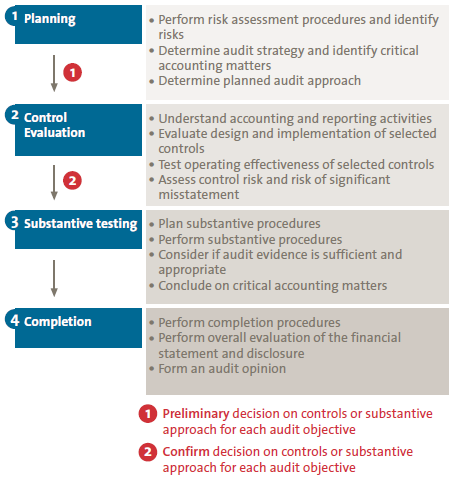

Audit methodology alignment and integration

The fourth key driver is – in our experience – the one that is overlooked the most. People tend to see it as a given that auditors will embrace data analytics, once it is widely available to them. On the contrary however, we have seen that auditors are somewhat reluctant in changing their classical way of working in a more data-driven audit approach. The way that data analytics will be integrated within the audit program or audit methodology is a pivotal factor for success. The right decisions regarding the following topics need to be made:

- integrate the analytics in the audit methodology through a technology-centered approach (technology push) versus an audit-centered approach (technology pull);

- data analytics as a serviced add-on to the audit approach versus a fully integrated audit analytics approach;

- data analytics as pre-audit work to determine focus and scope versus data analytics as integral control testing to substantiate audit findings (or both!).

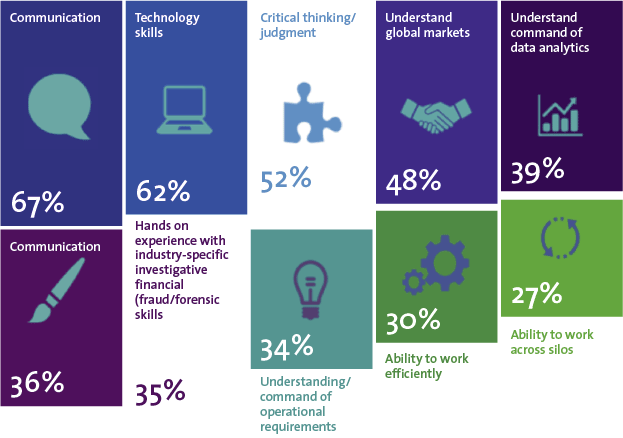

Skills, capabilities and awareness

The last defined driver for success is the skillset of the auditor to fully leverage data analytics. The skillset does not only imply the execution of the analytics, but also how to present the analytic results, and explain its implication to the business and the auditee. It is vital that the message comes across clearly, and how the analytics support the audit findings. This requires both technical knowledge regarding the analytics process and generic audit know-how, but most importantly it requires in-depth knowledge on the data the analytics have been executed on. The following key choices need to be made:

- relying on well-equipped data analysts to execute and deliver audit analytics versus training the auditor in order to equip him or her to execute audit analytics;

- relying on data analysts to interpret and understand analytics results and its impact on the audit versus relying on the auditor to understand the data and the executed analytics and its impact on the audit.

The crucial choice that needs to be made, is whether you will rely on the auditor to further deal with the audit analytics, or will they be assisted by a data analyst to perform the technical part of the audit analytics? If you choose the latter, you will be faced with the challenge to create an effective synergy and collaboration between the two, where the analyst understands the data and the executed analytics (and visualizations), and the auditor can put the implications of the analytic results in place for the audit findings. To create such a synergy might not seem a major challenge at first. We have however experienced that data analytics is not part of the DNA of all auditors, and therefore it might be a bigger step to take then initially presumed.

Model: drivers for success

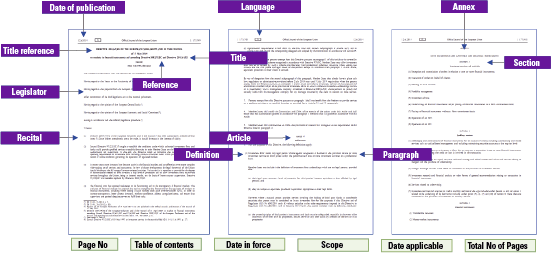

When we summarize our experiences in a visual overview, it would look like the model presented in Figure 2 below. The model shows the interconnection between all the five drivers that have an impact on the success of your data analytics implementation. A decision made regarding one of the key drivers will in the end influence the decisions that have been made regarding one or more other drivers. Each organization that is about to implement data analytics must find the right balance between the identified drivers for success.

Figure 2. Key drivers for success. [Click on the image for a larger image]

Implementing data analytics – a balancing act

Does having this model make audit analytics successful? For Randstad, it is not this model that made audit analytics where it is today. Assembling all the lessons learned and the root cause analyses of all the ‘failures’ the organization experienced, this model emerged. It is as such a reflection of what management has learned in the journey so far. At the same time, it is a means to an end: it facilitates discussions in evaluating where an organization stands today regarding analytics, and which key challenges need to be addressed next. It thereby supports management conversations and decision-making moving forward.

Ultimately, it is all about bringing the configuration of the different drivers in balance. In implementing audit analytics, Randstad has, so far, failed repeatedly. In most cases the lessons learned analyzed: where there is pain, there is growth. It identified that an unbalance in the configuration of the drivers was the root cause.

There are multiple factors to be addressed during the implementation. These factors can sometimes be opposites of each other, creating a ‘devilish elastic’. In the Randstad journey a big push was made to set a central solution, facilitate a technical platform and integrate analytics in the audit methodology. In the course of 2017 a lesson learned was picked up from this push: the projects that were run centrally yielded positive results. It did not translate however into the global risk and audit community to start running audit analytics throughout their internal audit projects.

Randstad has set the technology and methodology; the key is to now also bring the professionals to the same page in the journey. As audit analytics in its potential, fundamentally changes the way you run audits, it also means changing the auditor’s definition of how to do its work. Overwriting a line of thinking that has been there for a very long time is maybe one of the biggest challenges there is. Therefore, when the questions are asked on what Randstad is doing currently to implement audit analytics, and what the current status is, the answer is as follows: ‘To get audit analytics to the next level, we are currently going through a soft change process with our risk & audit professionals, to get them to not only embrace the technology, but also the change in the way we perform our audits as a result. Overall, we are at the end of the beginning implementing audit analytics. Ambitious to further develop and grow, we are looking forward to failing very often, very fast.’

Concluding remarks

In this article we summarized the importance of data analytics in the internal audit, the road that Randstad has taken to implement audit analytics, the challenges and lessons learned along the way, and how these lessons can be translated into a model of key drivers for success. The goal of this article is to codify our journey and corresponding lessons learned, and communicate the experiences to the audit community, so they can profit from them.

The important message that we want to communicate, is that implementing audit analytics is far from just a technological challenge. By implementing data analytics, a large change is brought to the internal audit organization. The auditors need to change their way of working, and make a paradigm shift towards a data-driven audit. One cannot underestimate the implications of such a change by focusing mainly on the technological success of data analytics.

Reflecting on these developments and audit analytics initiatives, one should really take this paradigm shift into account. What does audit analytics mean in the old world, but also in the new world?

Ultimately a key challenge is how to go through the paradigm change, and how to support (or not support) auditors in making the paradigm change? Understanding and embracing audit analytics might not be their biggest challenge! Something Randstad Global Business Risk & Audit is working on, daily!