The geopolitical context of security is changing rapidly – as China rises, the US becomes more protectionist, and the EU is struggling to flex its geopolitical muscle – and at the same time the technological base of virtually every form of security infrastructure is going through revolutionary, and often little understood, innovations – from Chip manufacturing to AI to 5G. We are now at the cross-roads of managing it. How can our open society remain strong in the face of foes and its own fragility, without sacrificing – and instead leveraging – its openness?

Introduction

We are on the verge of large, global changes. Technological breakthroughs from the fourth industrial revolution are affecting our daily lives. Meanwhile, Western society is being rivalled by strong competitor Asia, and especially China. How does Europe avoid being squashed between America First and the Chinese Dream? How do we leverage the innovations from Artificial Intelligence and the Internet of Things without getting bogged down in geopolitics around 5G or ASML exporting EUV machines to China?

This article discusses the new security nexus of security, geopolitics and digitalization. As we will show, these topics are heavily intertwined. China’s New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan offers an outlook for the People’s Republic to become the global leader in Artificial Intelligence (AI) by 2030, and their Made in 2025 strategy is aimed for China to become the new global manufacturing, cyber, science and technology innovation superpower. History teaches us that those who set the technical standards will dominate the world (see box “Developing technology is key in the power shifts”). Add into the mix China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which encompasses over 1 trillion USD in investments (see box “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the facts”), establishing China’s influence on the Eurasian content by investing in all kinds of physical trade infrastructure, such as dry ports, shipping routes and railways. We can conclude that China plans to re-establish both a digital and a physical silk road.

Developing technology is key in the power shifts

Throughout history, those who defined the technical standards, ruled the world ([Wijk19]). In the 19th century the United Kingdom ruled the technical standards and in the 20th century the United States. Even the Netherlands ruled the seas by virtue of its unparalleled skills in maritime engineering during the 17th century. China is currently taking over this role with their investments in Artificial Intelligence and 5G. China plans to be the leader in AI by 2030 through their New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan ([SCoC17]).

Meanwhile, this hegemonic shift from West to East motivates other countries to join the power game. This is especially apparent in the cyber security domain, where countries such as Russia, Iran, Israel, North Korea and of course America and China are increasingly active. Nation state and organized crime driven cyber-attacks are not only aimed at financial gains, but lately more and more on gaining political influence, acquiring intelligence, preparing for hybrid warfare or disrupting enemy infrastructure. Dutch companies and governments are well prepared to prevent cyberattacks, but they don’t dare to face the inevitable truth that they will be hacked. They are ill-prepared to detect and respond to such attacks.

The latter is particularly worrying in times where our social dependencies on digital infrastructure is rapidly increasing. Consider examples such as AI managing factories based on sensor data, autonomous cars or connected cars based on 5G and image recognition, algorithmic profiling of civilians, social credit systems based on face recognition. These examples will change our lives drastically, if not today then tomorrow. How do we manage trust and security in these complicated digital infrastructures that – upon disruption – may lead to social disturbance?

We are now at the cross-roads of managing it. How can open society remain strong in the face of foes and its own fragility, without sacrificing – and instead leveraging – its openness?

We are convinced that hegemonic and technological changes present us with threats and show us our weaknesses, but we are moreover convinced that these changes offer us opportunities to build on our strengths as a Dutch and European society and benefit from the uncertainty these big changes cause. Common wisdom has it that you can’t solve new problems with old methods. So, we will need new strategic leadership to effectively deal with the new security nexus. In fact, every important historical moment is marked by these sorts of shifts to new social models, which expand in velocity and complexity well past what the current ways of thinking can handle. Our predicament is no exception. And usually the source of the greatest historical disasters is that so few people at the time either recognize or understand the shift ([Ramo09]). If any state has learned this lesson, it is China: by failing to understand the new networks, technologies and norms of global security of the mid-19th century, imperial China, as what had been the largest economy in the world for centuries and an untouchable regional hegemon for longer, was largely destroyed by relatively small European powers in a matter of years. We are, once again, on the verge of such a shift.

But now the cards have changed. For the first time since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Western society is faced with a successful rival model: China. As the European Commission said in its recently published China strategy ([EC19]): “China is, simultaneously, […] a cooperation partner […], a negotiating partner […], an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.” Moreover, the US has shifted its geopolitical course dramatically. President Donald Trump has already said he does not intend to pick up Europe’s security bill for much longer. Between America First and the Chinese Dream, Europe seems to be stuck in the middle.

Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the facts

Only six years after it was launched, it now encompasses over 1 trillion US dollars in investments. 1 trillion US dollars roughly equals Dutch GDP, net worth of Apple, Amazon or Microsoft, twice the EU Connectivity Strategy and ten times the US Marshall Plan.

China is investing in all kinds of trade infrastructure, such as dry ports, shipping routes and railways. It does so in more than 60 countries, in every continent, representing over two-thirds of the world population, covering land, sea and even cyberspace.

Most of China’s investments go to Western Europe, but since BRI, Central, Eastern and Southern Europe have been getting a lot of attention from China. Examples of investments are: financing a 1.1 billion US dollar railway between Budapest and Belgrade; buying a major stake in the Port of Piraeus; signing up of Italy as a BRI-partner, the first belonging to the G7; and setting up the 16+1 Platform – a diplomatic forum to engage Central and Eastern European states outside of the EU’s reach.

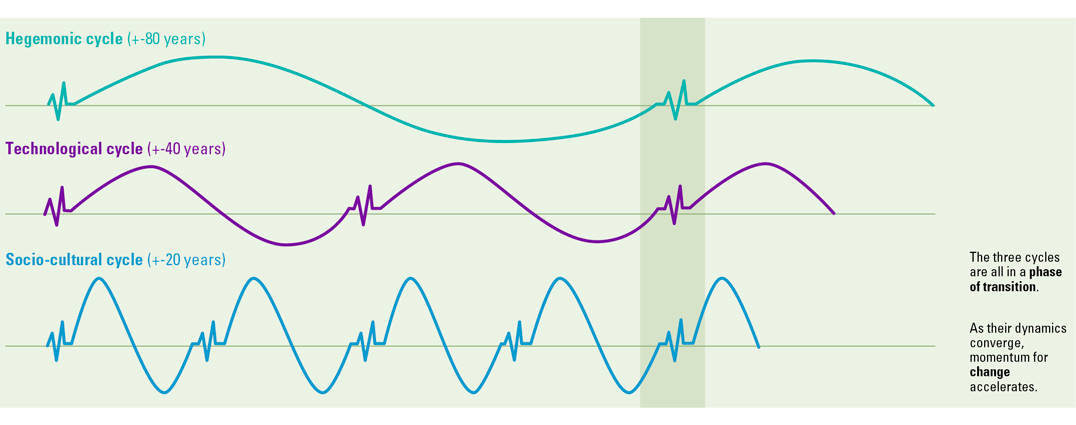

Cycles of conversion

Haroon Sheikh, researcher at the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR), puts the geopolitical and the technological aspects of disruptive changes in perspective by pointing out the cycles in hegemonic, technological and socio-cultural change (Figure 1, [Shei19]). These cycles tend to follow a pattern:

- every 20 years, a new generation changes society by pushing new cultural and social values;

- every 40 years, the workings of our societies and markets change fundamentally by virtue of technological breakthroughs;

- every 80 years, a new hegemonic power takes the lead in the geopolitical world order.

The exciting thing is that we have entered an era in which all three disruptive cycles are in a phase of transition, simultaneously.

Figure 1. Convergence of cycles accelerates change ([Shei19]). [Click on the image for a larger image]

This causes rapid, large and unpredicted changes. The geopolitical context of security is changing rapidly – as China rises, the US becomes more protectionist, and the EU is struggling to flex its geopolitical muscle – and at the same time the technological base of virtually every form of security infrastructure is going through revolutionary, and often little understood, innovations – from Chip manufacturing to AI to 5G. When we look at the current controversy regarding 5G and Huawei, we see these three cycles shifting right under our noses. The US and China are aware that who owns the fourth industrial revolution, will probably dominate global networks of power for decades to come, and will be able to push socio-cultural norms regarding freedom of information, privacy and security.

Technological cycle

To illustrate the technology cycle, we explore three perspectives of the changing world: hyper-connected ecosystems; blurring lines between physical and digital worlds; and the impact of algorithms and AI.

Perspective #1 From splendid isolation to hyper-connected ecosystems

Companies now operate in a complex world of hyper-connected ecosystems. Competitive advantage is often no longer based on the ownership of certain assets. The source of differentiation – and thereby economic value – rather comes from having access to the assets, by having a solid and strategic position in hyper connected ecosystems. Boundaries between organizations are fuzzy, and supply chains are integrated. Even innovation is often a joint process.

The positive effect is that a range of new innovations has unfolded. However, in this hyper connected world, companies have become far more dependent on their partners. In nearly every aspect of their processes.

Perspective #2 Physical = digital

In a nutshell: the fourth industry revolution is characterized by technologies that start blurring the lines between physical, digital, and biological spheres. The Internet of Things (IoT) takes a central stage in the fourth wave. Many objects, ranging from cars to buildings and from watches to thermostats, are now connected 24/7. The IoT grows with exponential pace and leads companies into a new reality with massive opportunities. 5G is at the core of this exponential growth, supporting all sorts of devices to connect to the internet at low cost in high-density areas.

Perspective #3 Algorithms guide our decisions

Artificial Intelligence is a game changer in many ways and brings the world innovations in many domains. It accelerates the fourth industrial revolution, and many companies feel the urge to jump on the bandwagon. This is understandable, as the “winner takes all”-effect may be strong in this domain. First-movers have a strong advantage as they feed their AI systems with sample data sooner than late-joiners. Late-joiners therefore have to go through the full learning cycle themselves. According to VNO-NCW ([VNO18]) first-movers have the advantage of providing better services sooner; they are the preferred choice over late-joiners.

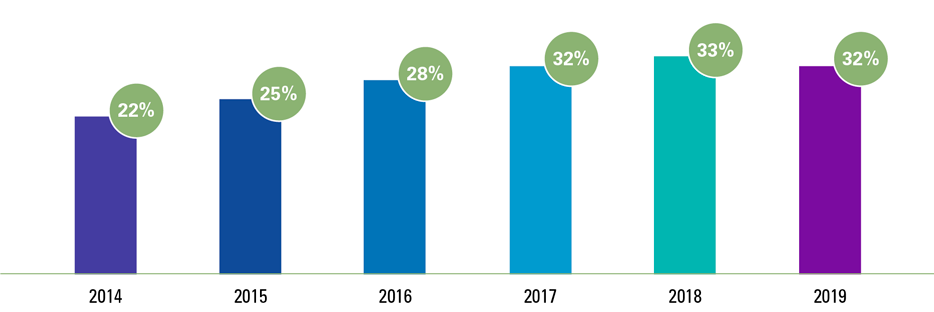

The technological antagonist

All three perspectives suffer from the same antagonist: cyber security. Many leaders in both the private and public sector fully understand the importance of cyber security for their business outcomes and objectives. The stakes are high. Not only in terms of the risk of interruption of vital services following attacks by malicious groups, but also in terms of digital espionage or theft of intellectual property. Experts estimate ([Lee18]) that commercial espionage may endanger economic growth to an amount of 55 billion euros and up to 289,000 jobs in the EU. According to a global survey by Harvey Nash and KPMG ([Harv19]), held with over 3,500 Chief Information Officers (CIOs) in over 100 countries, 32% experienced a major cyber-attack in the past two years (only 22% in 2014).

Figure 2. Number of CIOs that reported experiencing a major cyber-attack in the past two years ([Harv19]). [Click on the image for a larger image]

The motives behind these cyber-attacks vary. Some attacks aim for financial gains. The People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) has, according to the United Nations Security Council ([UNSC19]), gained over 2 billion US dollars by cyber-attacks on the financial industry to fund their Weapons of Mass Destruction programs.

Another category involves disrupting the enemy. We have for instance witnessed how Iran attacked the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Saudi Aramco) in 2012, wiping the hard disks of 30,000 computers ([Bron13]). Another example is Stuxnet, a virus that aimed to disrupt the Iranian nuclear program in Natanz ([Zett14]).

These cyber weapons can also be a means to gain political influence. Hackers of the Russian external intelligence agency SVR (going by the name Cozy Bear) have been accused of attacking the United States Democratic National Committee in 2015 to influence the 2016 elections.

Closely related to this is gaining intelligence. Edward Snowden, former NSA contractor, and website Wikileaks have uncovered many intelligence operations from the United States and the United Kingdom. Cases included spying on Belgian telco Belgacom and German Chancellor Merkel.

Last but not least, cyber weapons can be deployed for hybrid warfare. Conflicts between states take place largely below the legal threshold of an open armed conflict, with the integrated use of means and actors, aimed at achieving certain strategic goals ([Grap19]). These means frequently include cyber weapons or fake news ([ANV18]). For example, The Dutch Military Intelligence has, according to journalist Huib Modderkolk ([Modd19]), supplied the United States with telecom intel from a Dutch marine vessel equipped with specialized NSA equipment. This intel is used to conduct targeted killings with the help of the location of SIM cards, blending conventional weapons with cyber intelligence.

The face of (cyber) security is changing

In the traditional perspective on security, one would know the players and understand their relationship with other parties. In the digital era, this has changed. The lines are blurring between three perspectives:

- Coalitions are multidimensional: friends may be part-time enemies

- Israel has been accused of deploying very sophisticated malware against Swiss hotels where the P5+1 conversations concerned the Iranian nuclear deal between US, UK, Germany, France, Russia, China and the EU with Iran ([Gibb15]).

- Recently, Israel has been accused by The Guardian ([Holm19]) of deploying sophisticated devices near the White House to spy on cellular networks likely used by Trump and his staff.

- Private morphs into public: large corporates may have even more influence than governments

- Collaborations between state and non-state actors on cyber espionage are common practice, especially in China and Russia. However, also the United States have also been caught mixing private and public matters: the NSA echelon program was used to spy on the Airbus negotiations with Saudi Arabia, a contract eventually won by Boeing ([EP14]).

- Another important factor is the sheer power that some large tech companies have because of the size of their customer base.

- Breaches and espionage may be untraceable for a long time

- One of the differences between physical security and digital security is that in the latter case, there often are no “smoking guns”. Attackers can penetrate systems and infrastructures unnoticed.

- Preparation for cyber warfare may require to pre-emptively break in at soon-to-be enemies. To execute certain types of attacks, you need to already be in the enemy network.

Exemplary case study

A compelling case study where all of these factors come together, is a real-life event that is an exact copy of the Hollywood classic James Bond – Tomorrow Never Dies. In the movie, media mogul Elliot Carver lures the United Kingdom and China into war by sending fake GPS signals to a British navy ship. The ship thinks it is in international waters, but actually drifted into Chinese waters.

In the summer of 2019, Iran very likely (but unproven) lured a British oil tanker into Iranian waters by sending fake GPS signals. This allowed the Iranian military to easily capture the oil tanker, without leaving their own waters. This happened two weeks after British forces captured an Iranian oil tanker near Gibraltar accused of violating sanctions on Syria ([Hugh19]).

The use of technology disruption by Iran, likely with the help of Russian technicians, was actively used in geopolitical tension between Iran and the United Kingdom. In line with all hybrid types of warfare, there is no compelling proof Iran actually messed with these GPS signals, and this will likely never be proven.

How to respond to this new reality

Companies in the Netherlands and the European Union will likely experience the effects of this new reality in one way or another. Albeit as collateral damage of an attack on certain industries or economies in general, by being (overly) regulated by authorities, or by being too focused on adoption rather than securing new technologies.

We present four predictions and response strategies that will be important for 2020.

Prediction #1 The speed of technology adoption is challenged by new attack surfaces

The previous buzz around new technologies (cloud, AI, blockchain, IIoT and the like) resulted in rapid adoption in businesses. There is an increasing number of large corporates implementing these technologies to stay at the forefront of their industry, not to be disrupted. However, many of these technologies dig holes in the classic technological wall around their corporate castle (the old-fashioned “Fort Knox” doctrine). The Chief Information Officer is losing grip of data and information in his/her ecosystem, while uncertainty in the sense of IIoT (sensor) equipment and AI/ML algorithms is marching in. Lately, these moves are orchestrated by the newly introduced Chief Digital Officer, who often surpassed the CIO in corporate hierarchy.

Let us be clear: we don’t necessarily see a risk in lowering the castle drawbridge with the introduction of these technologies. They can be well-guarded when the classical security and control regime has been part of the project adopting these technologies. It is key to involve technology and security experts from the start (e.g. business case development, business readiness assessment and tool selection) to implementation (e.g. security configuration, security testing and security control implement) and finish (e.g. post-implementation assessment, continuous security control monitoring and periodic security assessments).

Prediction #2 Increasing debate over foreign investments and sales

There is an increasing national and international interest in foreign investments in technology companies. European technology companies will be under scrutiny both for direct investments as well as investments in their key suppliers or clients. International treaties and arrangements will be increasingly exploited for geopolitical power play, especially between the US and China (see the ASML case mentioned in the introduction). Furthermore, we’ll see a call for supply chain transparency where manufacturing and high-tech companies are expected to provide insight or even assurance over their full supply chain.

For now, the Netherlands has taken a relatively neutral stand in the upcoming Technology Decoupling between the US and China. The European Union seems to move towards Member State sovereignty on this topic, leaving each country to decide for themselves in e.g. the debate over Huawei. However, we strongly encourage Dutch corporates to start constructing a scenario that is relevant to their industry: what if a Chinese investor is interested in taking over a (major) part of our company ; what if my key supplier receives large investments from Russia or is entirely acquired by a foreign state-funded investment vehicle; what if my key supplier moves its business to countries that heavily invested in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative ; what if the authorities halt my exports to Iran, China or Russia ; etc.

Prediction #3 Rise of online borders

Large technology companies (usually based in the US) have been under scrutiny by the European Union for a while. The recent announcement of the EU Data strategy and policy options for AI (d.d. 19 February 2020) provides a lot of clarity for what is to come. The EU will regulate “high-risk” AI applications, scrutinize market power of large digital platform companies and increase EU data protection efforts. Furthermore, it will further stimulate the development and deployment of lower-risk AI applications. This will have its effects on Dutch and EU corporates in the sense that we will see increased pressure for in-country or in-EU data processing; potential exclusion of overseas technologies; and strong regulation of privacy-invasive AI applications such as facial recognition. This will increase difficulty to work cross-border (especially outside the EU).

While there is no consensus over the AI strategy of the EU (which is now up for consultation with European citizens, Member States and other stakeholders), large corporates need to closely follow and interpret the work published by the EU relevant for their industry. Most of the published policy options for AI are not new and rely on the work of the High-Level Expert Group AI (HLEG AI). Their publications can be very helpful for relevant scenario planning. We especially encourage corporates with an EU-only presence to look closely at their key (IT) providers and identify potential problematic providers or services. With increased investments from Member States and the EU in local AI development and deployment (in 2020 expected to be close to 20 billion euro), we will likely see EU competitors to invested US companies emerge soon.

Prediction #4 Increasing blend between cyber-criminal gangs and state-sponsored hackers

On the technological side, we see a more increased blend between hackers of cyber-criminal gangs and state-sponsored hackers. These gangs are probably hired as mercenary armies by states to inflict harm to or gain intelligence from their targets. This means that we see more sophisticated attacks, leveraging nation-state cyber capabilities delivered by crooks. Furthermore, these attacks will likely be more covert: currently, these gangs immediately announce themselves to e.g. retrieve bitcoins as ransom, while their new bosses demand them to silently disrupt enemy infrastructure or steal secrets.

All cyber experts agree on one thing: detection and response are more important than (solely) preventing cyber incidents. Currently, in this light, Dutch corporates are not in good shape ([WRR19]). We encourage them to:

- understand themselves (e.g. through crown jewel assessments) and their threat landscape (e.g. through threat assessments);

- validate their preventive capabilities (e.g. through penetration testing);

- but especially detective capabilities (e.g. through red teaming assessments);

- and to prepare for a breach (e.g. through (technical) cyber incident simulations).

Conclusion

We have discussed the fourth industrial revolution, its connection with digitalization and how it will change the world we know. Cyber security will play a dominant role in this revolution, with a wide range of interested parties and varying motivations.

We know that China is moving forward to soon become the world leader of the fourth industrial revolution by its vast investments in the digital and physical Silk Road. America however is not ready to give up this hegemonic position soon, and therefore Europe should avoid being squashed between America First and the Chinese Dream.

Europe has been a soft power nation in a hard power world, pushing its opinion in the form of legislation. Europe has been very successful, for example with the GDPR which is now the de facto global standard. The recently published EU Data strategy and policy options for AI is exactly aimed at this.

To put it in the words of the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen: “Today we are presenting our ambition to shape Europe’s digital future. It covers everything from cybersecurity to critical infrastructures, digital education to skills, democracy to media. I want that digital Europe reflects the best of Europe – open, fair, diverse, democratic, and confident.” Let’s all work together to reach this goal.

This article is based on an article published by KPMG the Netherlands and the Clingendael Institute as a preparation for the Dutch Transformation Forum. The complete article can be found here: https://home.kpmg/nl/nl/home/insights/2019/11/gaming-the-new-security-nexus.html

References

[ANV18] Dutch National Network of Safety and Security Analysts (ANV) (2018). Hybrid Conflict: The Roles of Russia, North Korea and China.

[Bron13] Bronk, C. & Tikk-Ringas, E. (2013). Hack or attack? Shamoon and the Evolution of Cyber Conflict.

[EC19] European Commission and HR/VP contribution to the European Council (2019). EU-China – A strategic outlook.

[EP14] European Parliamentary Research Service (2014). The ECHELON Affair: The European Parliament and the Global Interception System Study.

[Gibb15] Gibbs, S. (2015, June 11). Duqu 2.0: computer virus ‘linked to Israel’ found at Iran nuclear talks venue. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jun/11/duqu-20-computer-virus-with-traces-of-israeli-code-was-used-to-hack-iran-talks

[Grap19] Grapperhaus, F.B.J. (2019, 18 April). Kamerbrief over maatregelen tegen statelijke dreigingen.

[Harv19] Harvey Nash, KPMG (2019). CIO survey 2019.

[Holm19] Holmes, O. (2019, September 12). Israel accused of planting spying devices near White House. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/12/israel-planted-spying-devices-near-white-house-says-report

[Hugh19] Hughes, C. (2019, July 20). Iran tanker crisis: MI6 probe link to Putin after British ship is seized. The Mirror. Retrieved from: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/iran-tanker-crisis-mi6-probe-18458279

[Lee18] Lee-Makiyama, H. (2018). Stealing thunder: Cloud, IoT and 5G will change the strategic paradigm for protecting European commercial interests. Will cyber espionage be allowed to hold Europe back in the global race for industrial competitiveness? (No. 2/18). ECIPE Occasional Paper.

[Modd19] Modderkolk, H. (2019). Het is oorlog, maar niemand die het ziet. Amsterdam: Podium.

[Ramo09] Ramo, J.C. (2009). The age of the unthinkable: Why the new world disorder constantly surprises us and what we can do about it. London: Hachette.

[SCoC17] State Council of China (2017). New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan.

[Shei19] Sheikh H. (2019). Cycles and dynamics of change.

[UNSC19] United Nations Security Council (2019). Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009). Retrieved from: https://undocs.org/S/2019/691 S/2019/691

[VNO18] VNO-NCW (2018). AI voor Nederland: vergroten, versnellen en verbinden.

[Wijk19] Wijk, R. de (2019). De nieuwe wereldorde: Hoe China sluipenderwijs de macht overneemt. Amsterdam: Balans.

[WRR19] Wetenschappelijk Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid (2019). Voorbereiden op digitale ontwrichting.

[Zett14] Zetter, K. (2014). Countdown to Zero Day: Stuxnet and the launch of the world’s first digital weapon. New York: Broadway Books.