An emerging regulatory and reporting environment is increasingly forcing companies to integrate circular economy. This process poses both challenges and opportunities. The Circular Transition Indicators (CTI) gives companies an opportunity to measure their circular performance, enabling strategic choices and alignment with reporting requirements.

See also Compact 2022/1 “ESG & GRC: how to maneuver?”.

Introduction

Circular economy has emerged as a strategic lens to operationalize sustainability ambitions. In our current economic system, linear production methods of “take-make-dispose” are still prevailing ([Kirc17]). The circular economy is an economic model combining three principles: eliminating waste and pollution, retaining the value of circulating resources, and regenerative nature by design ([EMF22]). The 2022 Circularity Gap Report showed that the world is only 8.6% circular ([CiEc22]) which is insufficient to maintain a livable and thriving world.

To address the need for action, policy makers have reacted by pulling out the carrot and waving the stick, increasing the pressure on companies to incorporate circular principles but also to transparently show progress to the world. Emerging regulatory developments and directives create both challenges and opportunities for businesses, for example through the European Green Deal. We have arrived at the point where it is time for companies to develop a clear circular economy strategy to turn these compliance risks into new opportunities.

Transitioning towards circularity is not a simple task. Not only do companies need to develop and set circular economy targets; they also need a metric system that supports the reporting and decision-making processes. In 2018, KPMG and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) collaborated to develop the Circular Transition Indicator (CTI) framework, a circular metric framework developed with businesses and for businesses. This was an answer to a need for more uniform definitions and a consistent way of measuring circular performance. This development already started before the larger and speedier uptake of circular economy related regulations began. In this article, an overview of regulatory developments relevant to the circular economy is provided, together with details on the mechanism and benefits of the CTI framework.

Definition of circular economy

The circular economy is an economic model that is regenerative by design.

The goal is to retain the value of the circulating resources, products, parts and materials by creating a system with innovative business models that allow for renewability, long life, optimal (re)use, refurbishment, remanufacturing, recycling and biodegradation.

By applying these principles, organizations can collaborate to design out waste, increase material resource productivity and maintain resource use within planetary boundaries ([WBCS22]).

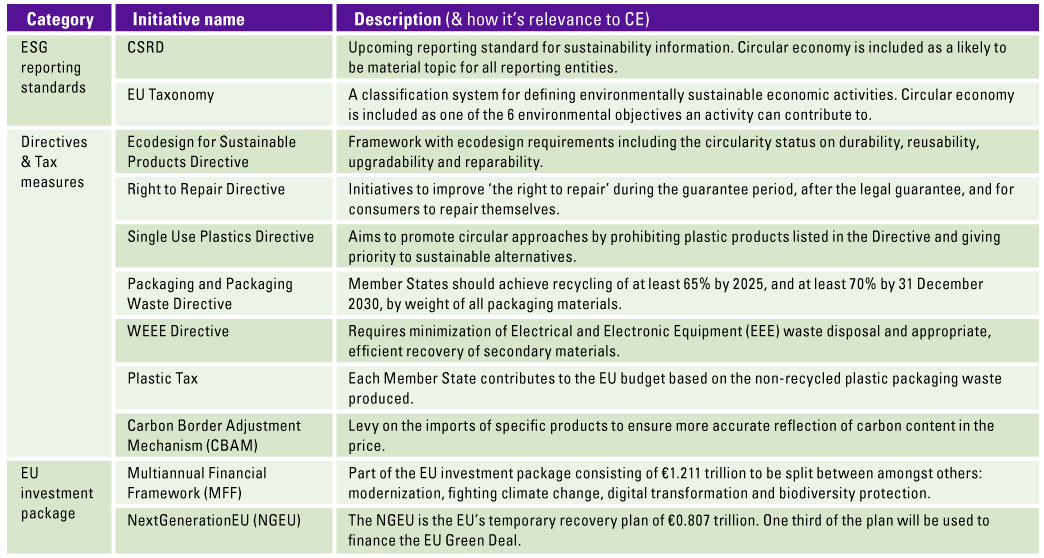

Embedding circular economy in business is becoming the new necessity through emerging regulatory trends

In December 2019, the EU announced its ambition to become climate neutral by 2050. To reach this ambition, the EU has mapped out a variety of policy initiatives which provide a clear message to industries to transition towards a circular economy. These initiatives have led to the development of new regulations of reporting standards, directives on resource efficiency and fiscal incentives and funding opportunities for circular innovations. See Table 1 for an overview of some of the key ESG reporting standards, directive & tax measures and investment programs. Hence, constant regulatory pressures and decarbonization challenges are increasingly driving companies to consider incorporating circularity into their operation on a greater scale.

Stringent disclosure requirements on material use are on the horizon

Increased attention towards ESG performance via more stringent reporting requirements and regulations has resulted in societal and corporate awareness to be at an all-time high. Due to new regulatory developments, circular economy is becoming mandatory disclosure for companies. The upcoming European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will amend the current Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). This amendment has made “resource use and circular economy” one of the key reporting topics and classified as “likely to be material” for all reporting entities ([EFRA22]). This regulation will apply to all large public interest entities (PIEs) subject to NFRD, all large companies meeting at least two out of the three criteria: 250 employees, €40 million turnover, and €20 million total assets. The scope also includes listed SMEs and non-European companies which generate €150 million turnover and have at least one subsidiary or branch in the EU.1 Another regulation being developed in tandem with, and a requirement under the CSRD is the EU Taxonomy, a classification system for defining sustainable economic activities ([EuCo22a]). The EU Taxonomy is based on six environmental objectives that an activity can contribute to, including “the transition to a circular economy”. Next to a quickly changing regulatory environment for circularity, major reporting frameworks are following suit. This is for instance the case for the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) that recently updated its reporting standard on waste via GRI 306 which requires companies to disclose their waste management ([GRI21]). Additionally, there are efforts to further standardize circular economy practices. A representative example is the ongoing development of ISO TC/323, a new ISO standard aimed at establishing internationally agreed frameworks for implementing circular economy practices. These developments build the case for companies to address circularity through measurement ([Issa18]).

Circularity is the missing piece of the puzzle of decarbonization

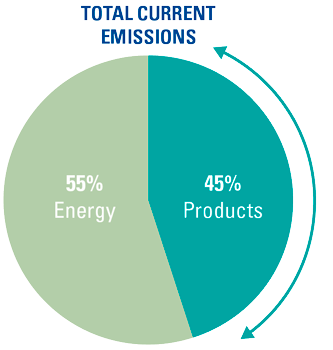

Circular economy is being recognized as an essential piece in the global quest for decarbonization. With global climate targets and the European 2050 net-zero commitment, institutions and companies are desperately looking for ways to decarbonize their current economic activities. While today’s emission reduction efforts mainly focus on energy transition and energy efficiency measures, these approaches pose two potential challenges. First, moving towards renewable energy systems will significantly increase the demand of relevant materials. The pace at which energy transition enabling resources need to become available to meet the 2 °C scenario will require circular solutions ([HEAD21]). Second, although such approaches can reduce emissions that are related to energy use, a 45% segment of total emissions remains that are associated with producing goods, as indicated in Figure 1. It is estimated that by applying circular economy strategies, almost half of the remaining emissions associated with production of goods can be avoided ([EMF19]). These estimates do not take into account developing insights, which show that the proportion of emissions related to material use is even higher ([CiEc22]). At the same time, tax levied on embodied carbon will become more stringent according to EU’s upcoming regulation on Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). As additional tax will be applied for a range of imported goods to reflect their carbon content, companies need to put in extra efforts to build a more circular and domestic supply chain.

Figure 1. Total emissions breakdown and emissions reduction potential of circular economy strategies (source: Ellen MacArthur Foundation). [Click on the image for a larger image]

Emerging regulations are addressing waste and there are vast opportunities for frontrunners

The Circular Economy Action Plan was drawn up as one of the main pillars of the European Green Deal. Detailing 35 action plans across eight policy areas, the initiative has been a fuel that drives the development of directives that push the circular transition forward.

Examples include directives to significantly reduce waste, such as the Single Use Plastics Directive. The directive prohibits the use of single-use plastic products that can be easily substituted and sets clear targets for the collection and incorporation of recycled content. Similarly, the Waste and Packaging Waste Directive follows, which sets targets for the % of waste and waste per material that should be recyclable ([EuCo22b]). It also stipulates clear % recycling targets for packaging materials. A tax scheme on plastics has been introduced to further such efforts. Under the Plastic Tax, Member States need to make a contribution to the EU budget based on the amount of their non-recycled plastic packaging waste. Each Member State has autonomy in how it wishes to impose the tax, however it is up to companies in finding ways to address additional financial burden. Efforts to minimize waste are ongoing in other sectors as well, for example a directive for Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) ([EuCo22d]). The WEEE Directive, with recent updates, requires companies to ensure responsible e-waste disposal and efficient recovery and recycling of valuable materials.

Another part of directives focuses on the lifetime extension of products. Right to Repair is a movement which is gaining traction and local regulations have emerged to make retailers and producers responsible beyond the point of sale. Right to Repair Directive of the EU ensures that the repair is possible during and after the legal guarantee, and that the right is ensured for consumers to repair products themselves. A proposal for new Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Directive was presented in March, which will broaden the scope of existing Ecodesign Directive and address various sustainability and circularity aspects of products. This will include requirements on product durability, reusability, upgradability and reparability.

The uncertainty posed by a developing regulatory landscape can be burdensome on companies. However, the increasing awareness of policy makers does not only pose compliance risk to companies but offers clear opportunities for those that take active steps towards improving. Funds to finance the green deal will be mobilized through the EU’s long-term budget Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), coupled with NextGenerationEU (NGEU) the temporary instrument designed to boost the recovery. With a value of €2.018 trillion in current prices, this will constitute one of the most significant stimulus packages ever in Europe. The aim is to strengthen a post-COVID-19 Europe ([EuCo22c]). Next to improving the future of Europe, these developments create a clear business case for circularity.

Table 1. Regulatory developments in Europe relevant to circular economy. [Click on the image for a larger image]

While such initiatives drive companies to put circularity higher on the agenda, the adverse effects of recent supply chain disruptions make that companies even further realize the benefits of implementing circular economy strategies. The supply of resources can face unpredictable disruptions in their supply chain due to a variety of factors, such as geopolitical issues, natural disasters and disease. The ongoing global supply chain disruptions during the COVID pandemic is an evident example of this. These risks become highly relevant to critical materials which are common and crucial ingredients for strategic technologies such as renewables, e-mobility, and ICT. Often, these materials only have few supplier countries and hold high economic value, increasing the impact of potential risks. Acknowledging these supply risks, companies can benefit from incorporating circular economy strategies to build a more resilient supply chain.

Witnessing the clear benefits, more companies are gearing up to incorporate circularity into existing business models. Along with the trend, the demand for measuring and tracking companies’ circular progress emerged. As an answer to the demand, the Circular Transition Indicators (CTI), a circular metric framework was developed by WBCSD with the support of KPMG in 2018. The framework has been updated on a regular basis since its initial introduction, with CTI version 3.0 launched in May 2022. The framework is developed with a large number of companies across different sectors with the aim to provide a comprehensive, consistent methodology for circular performance measurement and insight for improvement.

Through CTI, companies can lay the foundation for a clear metric to track circular progress

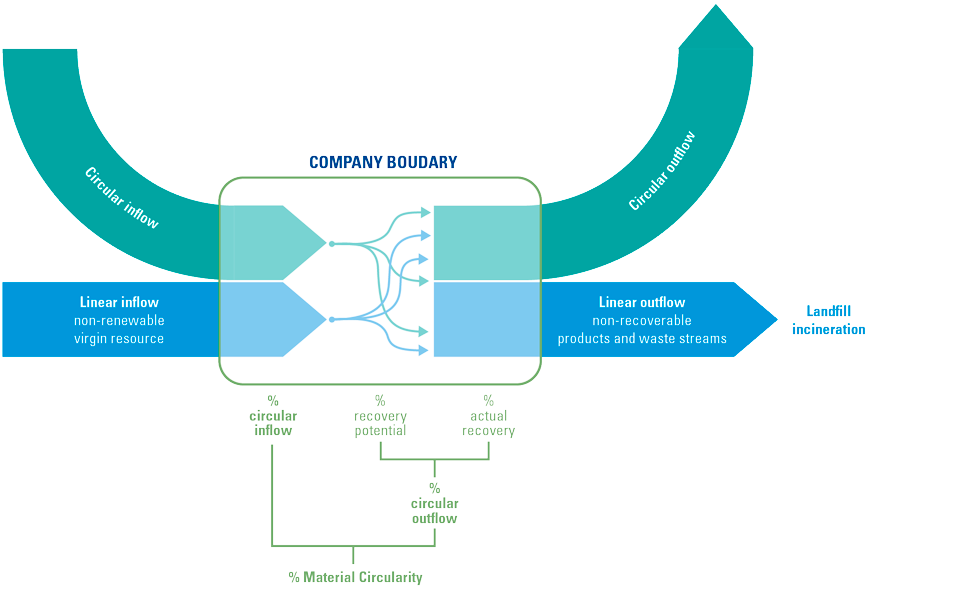

CTI allows companies across all sectors and industries to measure their circular performance in a consistent way, giving insights into their capability to optimize resource use and reduce waste generation. Within the framework, the inflow and outflow of a company are assessed for circularity and the result depends on three key intervention points: circular inflow, recovery potential, and actual recovery as shown in Figure 2. The circular inflow indicates the circularity of sourced resources, materials, and products, for example because these are non-virgin (secondary) or renewable (biobased and sustainably grown). The recovery potential shows to what extent the company designs its products to ensure the recovery of the components and materials. For non-manufacturing companies this can be assessed based on supplier information. Lastly, the actual recovery implies how much of the outflow is collected and recovered in practice. Together, these intervention points provide insights necessary for a circular transition to different parts of business. Circular inflow provides insight for procurement; potential recovery can inspire design innovations such as design for disassembly or biodegradability. Information on the actual recovery can motivate business model innovation and drive new partnerships that incentivize return logistics and recovery.

Figure 2. Illustration of material flows used in CTI. [Click on the image for a larger image]

CTI provides four modules of indicators for extensive insights

CTI 2.0 had three modules consisting of a set of indicators: Close the Loop, Optimize the Loop and Value the Loop. In May 2022, CTI 3.0 was launched which introduced a fourth module called Impact of the Loop. The four modules of indicators enable companies to gain in-depth insight into their circular performance, the added value of adopting circular economy strategies, and the strategies’ potential impact on the companies’ climate and sustainability goals.

The Close the Loop indicators aim to gain a first insight into the circularity of the selected scope. The material circularity is determined based on the weighted average of the circular inflow and circular outflow. Next to these two required indicators, the module also provides insight into water circularity and renewable energy.

The Optimize the Loop indicators give a deeper layer of insights into the company’s use of critical materials and type of its resource recovery methods. With the percentage of critical inflow, it provides insight into the company’s dependency on materials that have been identified as critical. In addition, the module provides a breakdown of recovery types in the following categories: reuse or repair, refurbish, remanufacture, recycle or biodegrade. Indicators on actual lifetime can be utilized to understand a product’s average lifetime beyond the design life or warranty period. Companies can use these indicators to optimize and refine their circular economy strategies.

The Value the Loop indicators inform about the business value added by the company’s circular material flows. The circular material productivity indicator gives insights into the decoupling of linear material use from the revenue generated by companies. The CTI revenue indicator can be calculated to measure the financial benefits associated with circular performance and can be used for portfolio steering to drive towards more circular sales.

While the forementioned modules focus on quantifying a company’s circular performance, the newly introduced Impact of the Loop module aims to indicate the impact of a change in circular performance on sustainability objectives such as climate, nature, and social equity. The GHG impact indicator was recently introduced, and helps companies understand the potential GHG emission savings that can be achieved through adopting circular economy strategies. The analysis is conducted by comparing the emissions associated with the current material composition and the scenario of using recycled content. The indicator can provide a high-level indication on how a company can tackle emissions associated with material use thereby being an important piece in completing the decarbonization puzzle.

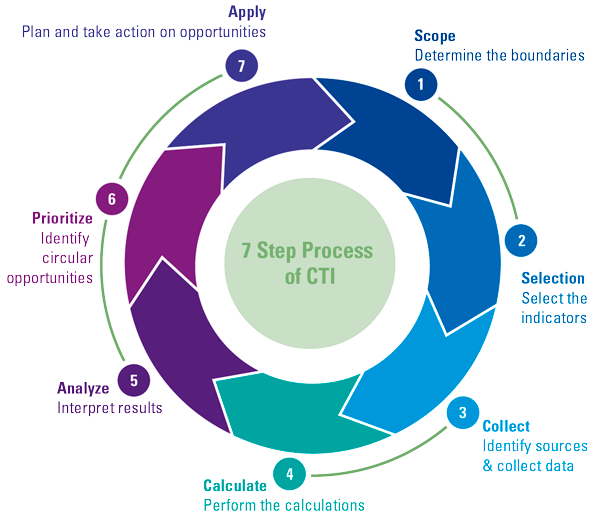

CTI utilizes a clear methodology consisting of seven steps

Applying CTI is a seven-step process depicted in Figure 3. KPMG groups the seven steps in three phases that companies can go through to start their journey on this continuous improvement cycle.

Figure 3. Seven-step process of CTI framework (adapted from CTI report ([WBCS22]). [Click on the image for a larger image]

Phase 1: Scope & Selection

In the first phase, the scope of the measurement and the selection of indicators to be included is determined. The company begins by clarifying the objective for measuring circularity, considering the desired type of insights and audiences to serve with these insights. Based on the intent, a more specific scope is determined, for example defining to which business level (i.e., product, portfolio, business unit, site, company) the process will be applied.

Phase 2: Collect & Calculate

The second phase consists of data collection and calculation. Close collaboration across the company’s value chain and various data owners is key in this step to obtain the data as accurate as possible. The calculation using the collected data can be implemented via both a software dedicated to CTI (CTI Tool) or performed offline, depending on the company’s preference.

Phase 3: Analyze, Prioritize, & Apply

In the final stage, CTI supports companies in analyzing the outcomes, enabling them to build concrete future steps for improving their circular performance. First, the outcomes on each of the indicators are analyzed to identify areas of improvements. Risks and opportunities related to the transition towards a more circular economy are assessed and steer the prioritization of the potential improvement. In the application phase this is translated in target setting and a concrete action plan for improving circular performance.

What gets measured, gets managed

The CTI framework has been widely adopted by companies in a variety of sectors. Their testimonies are a vote of confidence for the framework’s ability to measure and steer circular performance. Developed with and for businesses, the experience of companies prove how CTI effectively supports the corporate circular transition process both internally and externally.

“Acknowledging their key role in tackling today’s most pressing sustainability challenges of climate change, nature loss and growing inequality, companies around the world are escalating efforts to measure and improve their circular performance. The CTI framework serves as precious resource for companies in understanding circularity; how it can help them build resilience, while developing critical insights about their business and improving their sustainability performance.”

– Irene Martinetti, Manager Circular Economy at WBCSD

The CTI framework empowers companies to make informed decisions on circularity. By gaining a holistic overview of material and product inflow and outflow, companies can make strategic choices to achieve circular targets as the CTI assessments provide insight into the most important levers. Through applying circular economy strategies for materials critical to their business, they can build a more resilient and secure supply chain. CTI does not only allow companies to measure and track their progress; it can also support identifying strategic choices that can bring companies closer to their circular ambitions.

The CTI framework also contributes to accelerating the circular transition of companies by easing the communication and decision-making processes. By having a clear set of indicators, CTI helps companies to effectively communicate across the firm with a common language, from business unit to operational level. The enhanced communication can also help steer circular decision-making, for example during procurement processes.

The framework will also effectively support companies in communicating their progress externally. With a firm metric system to measure circular performance, companies can easily track their progress and have the figures ready for external communication. CTI is updated annually to stay aligned with the emerging regulatory environment and developments in reporting standards. Having figures ready which align with reporting standards will allow companies to become frontrunners in the race to meet new disclosure requirements in the coming years.

Conclusion

The need to embed circularity in the core of business is becoming apparent through an emerging regulatory environment, changing reporting standards and an ambitious EU long-term budget.

When starting your circular journey, you need to take various factors into consideration, including “how” to measure and track your circular progress. Circular metric frameworks such as CTI can effectively support companies as the ruler and the compass in your journey. Using a unified set of indicators, the framework will ease the communication between different business units and speed up the transition.

The developing regulatory environment regarding circularity and increasing material criticality indicates that the need for circular transition will only intensify in the coming years. CTI offers the means for business to measure and steer upon their circularity, thereby future-proofing the business. This will allow you to make informed decisions and communicate progress externally in line with developments in reporting standards. Additionally, it will allow you to align your circular decisions with broader aspects related to your corporate sustainability initiatives which marks an important step on your road towards becoming a frontrunner in sustainability. Now is the time to embark on your circularity measurement journey with CTI.

Notes

- In June the agreement has been reached, including reporting deadlines for entities to be set at: FY24 for companies covered by NFRD, FY25 for other large listed and non-listed companies, and FY26 for listed SMEs.

References

[CiEc22] Circle Economy (2022). The Circularity Gap Report 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://www.circularity-gap.world/2022

[EFRA22] EFRAG (2022). Sustainability reporting standards interim draft. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://www.efrag.org/Activities/2105191406363055/Sustainability-reporting-standards-interim-draft?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

[EMF19] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2019, 26 September). Completing the Picture: How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/rl0yth77pffc-jqkp5d/@/preview/1?o

[EMF22] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2022). Finding a common language – the circular economy glossary. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/glossary

[EuCo22a] European Commission (2022). EU taxonomy for sustainable activities. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en#what

[EuCo22b] European Commission (2022). Packaging waste. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/packaging-waste_en

[EuCo22c] European Commission (2022). The 2021-2027 EU budget – What’s new? Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/2021-2027/whats-new_en

[EuCo22d] European Commission (2022). Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-electrical-and-electronic-equipment-weee_en

[GRI21] GRI (2021, 8 February). Help for companies on circular economy progress. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/news-center/help-for-companies-on-circular-economy-progress/

[Head21] Heading, S., Walrecht, A., Dhawan, R. & Hasdell, J. (2021). Resourcing the Energy Transition: Making the World Go Round. KPMG International. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2021/03/resourcing-the-energy-transition.pdf

[Issa18] Issanes, M., Chevauche, M., Korter, M., & Perou, M. (2018). ISO/TC 323: Circular economy. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://www.iso.org/committee/7203984.html

[Kirc17] Kirchherr, J., Reike, D. & Hekkert, M. (2017, December). Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127 (December 2017), 221-232. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344917302835

[WBCS22] WBCSD (2022). Circular Transition Indicators v2.0. Retrieved 6 May 2022, from: https://www.wbcsd.org/contentwbc/download/11256/166026/1